Preparing the Leaders and Best for the Most Important Profession

How teacher education at U-M evolved and continues to push boundaries so teachers will be ready for the complex work ahead of them

Over the past 150 years, teacher training at U-M has evolved to meet changing needs, grown to partner with community schools and organizations, and demonstrated leadership in research-based innovations in student learning. Throughout expansions, contractions, shifting policies, and rotating leadership, U-M has remained among the best universities for the preparation of educators.

Professional teacher training in the state of Michigan was initially the responsibility of the Michigan State Normal School—now Eastern Michigan University—in Ypsilanti. The Normal School was, at the time, one of only six such institutions dedicated to teacher training in the United States and was the first normal school west of the Allegheny Mountains. Teacher training at U-M was initially viewed, in the words of President Henry P. Tappan in 1856, as a means to “prepare men to teach in the university itself, or in any other institution.” U-M would not immediately compete with the Normal School, which was focused on the elementary level, but did offer coursework designed to prepare high school teachers and school administrators.

U-M would soon take a leadership role in the field of education in the state. Professor John Dewey’s Michigan Schoolmasters’ Club, an association of local teachers and administrators as well as faculty members from both U-M and the Michigan State Normal School, began meeting in 1886 to “discuss matters that pertain to our common work, with particular reference to high school and collegiate training.” Dewey, who became the intellectual leader of progressive education reform upon publication of his book School and Society in 1899, was among the first scholars to emphasize child-centered learning. He favored the teaching of psychology in high school as a bridge to better learning in college, and proposed that the role of a teacher should be “largely one of awakening, of stimulation,” to allow the student to “realize the material in himself.” The Michigan Schoolmasters’ Club continued for 80 years.

Education at U-M came into even greater focus in the years leading up to the formation of a department. In 1871, a year after U-M began admitting women, James B. Angell was named university president. Angell was a major proponent of education and soon instigated a number of programs to grow Michigan’s presence in the field and prominence as an institution for teacher education. Before the end of his first year, Angell had begun the voluntary accreditation of secondary schools as a path for students into the university, taking the place of entrance exams. Under this scheme, high schools were reviewed by faculty committees to ensure high standards, and the program led to a “steady stream of well-prepared freshmen.” The Michigan model of foregoing entrance exams for students from accredited schools was revolutionary at the time, and contributed to what Dewey saw as a more democratized model of higher education “of and for the people.” But it was also controversial, and the presidents of U-M and Harvard feuded publicly over the new standards.

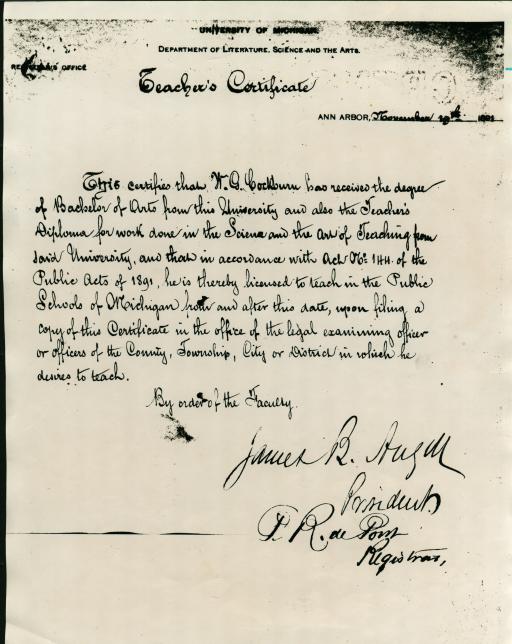

In 1874—soon after establishing this new model—U-M would offer another innovation in the field when the faculty approved a “teacher’s diploma,” a document which had no legal weight but testified to graduates’ qualifications to teach, backed by the prestigious university. Although in 1891, the Michigan legislature approved a teacher’s certificate to be paired with a degree, which created a legal qualification to teach at any public school in the state, the diploma also remained in use until the SOE formed in 1921.

“A large proportion of our students engage in teaching after graduation,” President Angell said in 1878, expounding on the need for a more formalized program of teacher training at the university. “Some adequate exposition of the science and the art of teaching, some methodical discussion of the organization and superintendence of schools, would be most helpful.” To this end, in 1879, William H. Payne was appointed Chair of the Science and the Art of Teaching, the first permanent chair of education dedicated solely to teacher training in an American college or university. A Harper’s Weekly editorial of the time lauded U-M as “upon another plane” compared with normal schools. The Normal School, perhaps understandably, objected to Payne’s appointment.

Burke Allan Hinsdale, who succeeded Payne as the second Chair of the Science and the Art of Teaching in 1888, labored to elevate education to professional status. His views were based more on his practical experience than theoretical philosophy. Hinsdale’s most significant achievement was winning for U-M the responsibility for the certification of teachers in Michigan, which was approved by the state legislature in 1891.

When Hinsdale resigned in 1900 due to declining health, Payne returned to Michigan and resumed the position of chair, which he held until his death in 1907. Allen Sisson Whitney assumed leadership of the university’s Department of Education upon Payne’s death, making his mark by expanding and invigorating the teacher training program. The culmination of Whitney’s work came in 1921 with the establishment of the SOE.

Whitney also oversaw the earliest formal relationships between the Department—and later, the School—of Education and community schools.

In 1911, the university signed a contract for teacher training students to observe classes at W.S. Perry Elementary School. But even with the observation and training provided at Perry, the faculty still wanted their own “demonstration school.” This led to the opening in 1924 of University High School, which held among its ambitions to “provide an education laboratory for scientific experimentation.”

University President Clarence C. Little, whose academic background was in biology, liked the idea of the school as a laboratory for other departments, which would also open new avenues of funding. “Education is in its infancy,” Little said in his address to the Michigan legislature in 1927 requesting that an elementary school be added to University High School. “Its fundamental sciences need to be studied, and it needs a laboratory in which to study them.” (It must be noted that Little’s legacy is problematic: he subscribed to eugenicist views and testified before Congress that smoking does not cause cancer. His name was removed from a U-M building in 2018.) University Elementary School opened its doors in 1930, though its role at the university was purely for research rather than student teaching in its early years.

University High School and Elementary School marked a significant turning point for the young SOE, but they did not spring up spontaneously. Many aspects of the development of the SOE would stem from its early focus on educational psychology. By 1916, the Department of Education offered a course in educational psychology, which may have been the first in the field. In the 1930s, William Clark Trow founded the first school psychology program in the state of Michigan and wrote the emerging discipline’s first textbook.

Howard McClusky arrived at the University of Michigan in 1924 with the specific purpose of working in the campus’s educational psychology laboratory—the first in the country. McClusky was interested in what he called “ecological psychology,” the effects of a community on students. He liked to “give away” psychology to parents, teachers, and other community members to help them understand how best to help the students in their lives. The progressive advances in educational psychology culminated in the creation of laboratory schools at U-M as part of the effort to conduct research within a school setting.

In 1922, a “coaching school” was inaugurated for teachers who held responsibility for high school sports teams and needed training from specialists. This summer program was a direct response to new laws mandating physical education in secondary schools. Soon, as more students specialized in this emerging field, the need for graduate programs became apparent. A graduate curriculum for physical education launched in summer 1931.

Though the university had initially only offered secondary-school teacher training (out of deference to the Normal School) the SOE began offering an elementary teacher preparation program in 1938, in response to growing demand for teachers in the state. The new program included the first methods course for elementary teachers and required one semester of practice teaching in the fourth year, but students were unhappy spending part of their final year away from campus. And so in 1942, the University Elementary School opened to student teaching. While this satisfied students’ desire to stay on campus and augmented the elementary school’s capability as a site for educational research, the “free democratic environment” of this school did not always match the schools where graduates would be employed. Most were able to adapt to their placements, but the disconnect emphasized the need to train students in a number of different student teaching environments.

After World War II, veterans’ return to campus and the baby boom led to a period of rapid growth. In 1943, 607 undergraduates and 1,254 graduate students were enrolled in the school; by 1948, those numbers had nearly tripled, to 1,825 undergraduates and 3,285 graduate students.

With two demonstration schools up and running and a novel course planned for physical education teachers, the school also branched out into preparing teachers to conduct adult education. The Program of Adult Education was established in 1938, growing into an extension service unit called Community Adult Education and, separately, into the Bureau of Studies and Training in Adult Education in 1947. The two worked together: the bureau was intended to further academic research in the field of adult education, while the extension service unit would serve as a laboratory environment. In 1950, the bureau became the Department of Community and Adult Education.

The school, being situated within a research university, was interested from its early days in educational theory improving practice. A 1955 newsletter mentions a new interdisciplinary program with the School of Architecture and Design (now the A. Alfred Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning and The Penny W. Stamps School of Art & Design) to incorporate elements of art and design instructional methods for use by “regular teachers.”

As the postwar period gave way to the Cold War era, the changing world put pressure on schools to adapt as well. The 1957 launch of the Russian Sputnik satellite led to a new emphasis on math, science, and foreign languages in schools as education became a national security priority. This new emphasis was supported by federal funding through the 1958 National Defense Education Act (NDEA), along with fellowships and loans for college students.

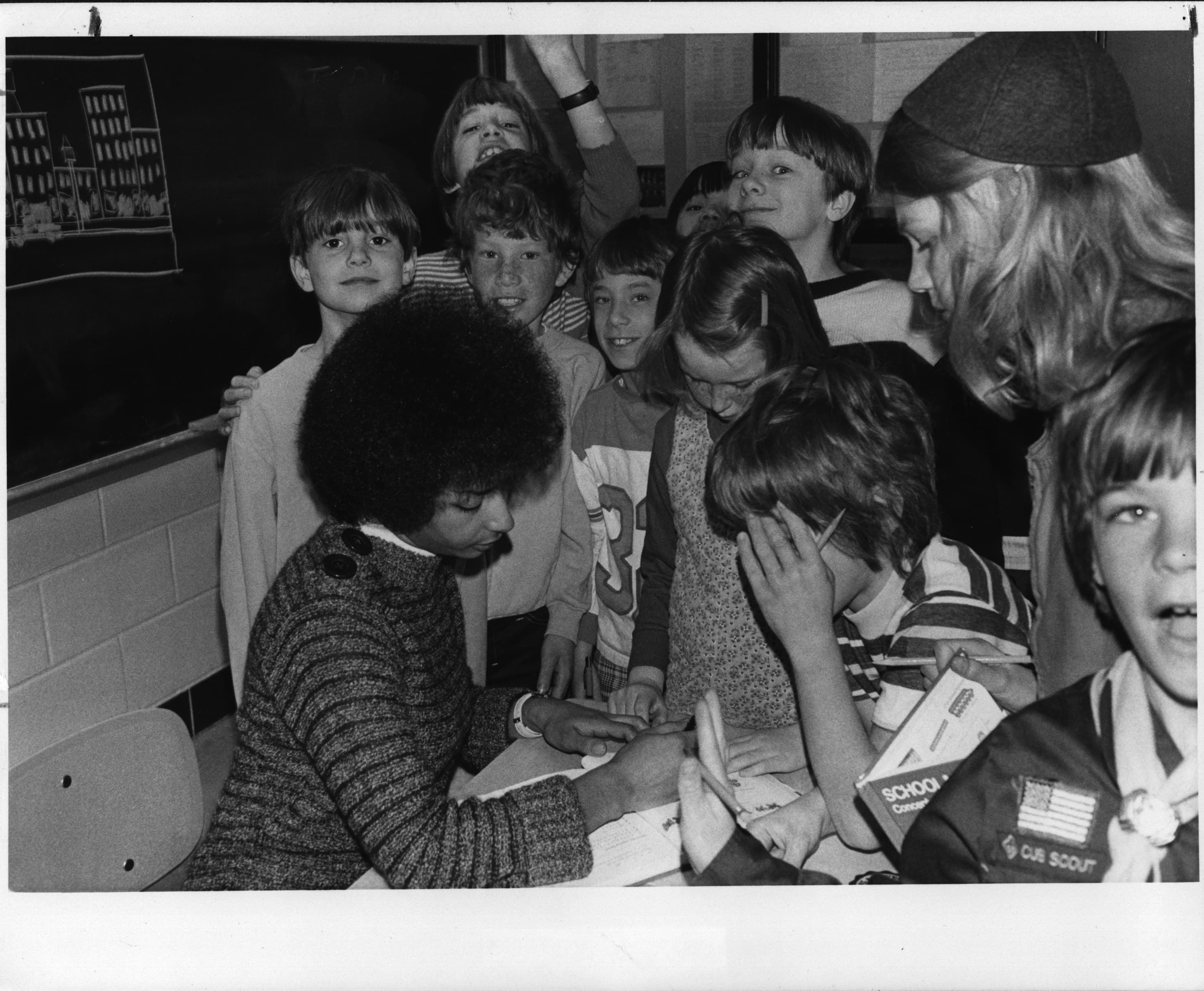

The civil rights movement led to an increased focus on remedying long-standing inequities in urban education. Professor Melvyn Semmel launched the Advanced Study in Elementary Core-City Teaching program in 1968, which enrolled teachers working in urban districts for at least three years to train with SOE faculty.

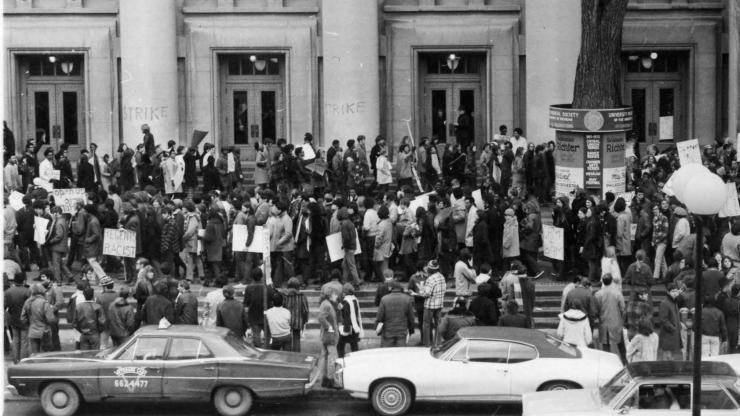

Wilbur J. Cohen, who became dean in 1969, placed a focus on urban education, including efforts to expand teacher training in urban schools and recruit a more diverse faculty to manage new programs.

In 1970, the federally supported Program for Educational Opportunity was introduced to provide schools with assistance in racial desegregation; that same year, the Program for Fair Administration of School Discipline began. Cohen’s efforts immediately grew the school’s teaching program: 1,471 candidates were recommended for teaching certificates in the 1970–71 school year, and an additional 1,367 degrees were earned that year by students in the SOE’s other undergraduate and graduate programs.

The rapid growth of the SOE did not last forever. In 1975, the Michigan State Legislature reduced funding for teacher education, citing an oversupply of teachers. The university had played a role in making a career in teaching a more desirable profession, only to become a victim of its own success as more people entered the field. This was the beginning of a period of severe contraction for the school, one which would see its budget reduced by 40 percent and physical education moved out of SOE a decade later.

Despite the intense challenges presented by the budget cuts, the refocused school continued to lead and innovate in several important areas throughout the 1980s. The SOE was an early adopter of emerging technology in teaching, recognizing its necessity in preparing students for an evolving workplace. By 1980, the school was already making use of computer terminals networked to the university’s mainframe, and in 1985 resources were significantly upgraded with an additional lab for “microcomputers,” individual workstations more akin to the desktop PCs still in use today. The availability of more computers allowed faculty to provide meaningful, hands-on instruction to a greater number of students, both at the introductory and advanced levels.

The school also continued to receive recognition for its excellence in teacher training and research, even during periods of severe upheaval. In the depths of its mid-’80s budget crisis, SOE nevertheless exceeded the rigorous standards of the National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE), which praised the faculty’s “outstanding” knowledge of the challenges then facing the field of education, as well as the “excellent scope of materials and equipment” available to students, including state-of-the-art computers and multimedia technology.

But in addition to the budget crunch, the 1980s also saw pressure to reform education from outside the campus. In 1983, the National Committee on Excellence in Education released A Nation at Risk, a broadside against the contemporary state of American schooling. Nation bemoaned “a rising tide of mediocrity” and a deterioration of American education that threatened “our very future as a nation and as a people,” calling for significant education reforms. This report informed much of the debate around teaching practice and school policy throughout the 1980s and ’90s, with different states and school districts attempting various reforms until the advent of the federal No Child Left Behind legislation in 2001.

Recalling the intensive study of education that resulted from the Russian space program of the 1950s, Professor William C. Morse suggested the need for a “Sputnik II Plus” initiative to address the dual anxieties of national defense and economic competition, two major challenges facing the United States in 1985. But, he stressed, the solution would not be confined to laws and policies. “We need to seek out new concepts to guide us if we are going to solve our problems,” Morse said.

In an effort to both inspire and be inspired by reform movements on campuses nationwide, in 1986 U-M joined the Holmes Group, a consortium of education deans looking to reform teacher education at research universities. Dean Carl Berger saw an opportunity for Michigan to serve a leadership role in the group since “we have already achieved many of the Holmes goals….We can bring the group exciting alternatives in teacher education,” he said. The Holmes Group at the time was focused on structures of recruiting and retaining exceptional teachers and highly qualified individuals they called “instructors” (who may serve in the classroom for only a few years), and provide meaningful incentives for those who embark on a career in teaching.

Michigan’s active role in the education reform movement would continue under Dean Cecil Miskel, who took over from Berger in 1988. “The School of Education must become deeply involved in the reform and improvement of American education,” Miskel said. “The enlightened self-interest of the university requires such involvement, not only because K-12 schools provide the university with its diverse and high-achieving student body, but also because the university’s key constituencies demand such involvement in return for public support.”

The bonds between the university and Detroit Public Schools were renewed during a symposium in June 1984, where preparation, recruitment, and graduation from U-M of Black students from Detroit Public Schools emerged as an explicit goal. The SOE was a leader in these efforts, focusing on improving social studies, language, science, and math instruction. The university’s CONFER system, an early computer program enabling networked communication, allowed faculty in Ann Arbor to offer a version of the International Conflict Simulation to Detroit students and teachers remotely. At this time, Dean Berger and education researcher Paul Pintrich were working with Apple to provide training for teachers to offer computing classes in Detroit high schools.

The technology collaborations with DPS took a number of forms in the 1980s. The SOE and Detroit Public Schools partnered on the Starnet Project, an early version of online classrooms focused on math and science education. The Starnet Project paired a live television broadcast of a lesson with functionality that would enable students to interact with the instructors and computers. The U-M center was one of five Starnet hubs nationwide and was seen as a way to immerse both students and teachers in innovative new methods of learning.

In addition to technological advancement and community partnerships, this era saw the school embark on another innovation that would transform teacher recruitment and training. In the 1990–91 academic year, the first five students graduated from the Master of Arts in Education with Secondary Teacher Certification (MAC) program, which was designed to serve students making a career change to education. Under this program, students spent a full school year in field placement while also enrolled full time in graduate study. Dean Cecil Miskel spoke about the MAC course during his comments before the U. S. Congress Subcommittee on Postsecondary Education of the Education and Labor Committee in 1991, regarding the reauthorization of Title V.

“We have created an alternative route to becoming a teacher that effectively addresses alleged shortcomings of traditional programs and point to new ways of looking at our schools of education as valuable national resources,” he said. Miskel cited a former accountant, a computer software salesperson, a bank executive, and others who returned to school to become teachers under the MAC program. The program was unique in several ways. Eligible students had to hold an undergraduate degree with a subject area minor; once admitted, they worked in cohorts of about 15 students. Courses were built around themes for each cohort, and students were either in class or teaching from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. every day. One of the most significant differences, however, was that the program was primarily field-based from the first day of class.

“The goal is to educate teachers who not only know their subject matter and how to teach, but also are reflective, critical thinkers,” Miskel said. Miskel noted that the program was already proving popular by its second year, when, without advertising, the school received 200 inquiries and 65 applications for a class of 30.

In 1997, the Master of Arts in Education with Elementary Teacher Certification (ELMAC) followed the success of the MAC program. Many of the first ELMACers were returning Peace Corps members. Like the MAC program, ELMAC also drew career changers who discovered their passion for teaching after years of being in the workforce. Both MAC (now called SecMAC) and ELMAC continue to be cohort-based one-year programs that provide an unparalleled cohesion between coursework and field placement experiences.

If the 1980s were an era of retrenchment for the school, of becoming “slimmer and trimmer,” the 1990s were a time of reinvention. The early years of the decade saw a reconceptualization of the early childhood education program, efforts that began with the 1991 formation of the Teacher Education Curriculum Committee, a group of faculty members studying and evaluating existing programs. Their recommendations were finalized in 1993 and these changes, including field placements for education students in each of the program's four semesters and an expansion of the cohort program, began to be implemented in the mid-’90s.

“There isn’t any one right answer about the best way to educate teachers, but I think we have the ingredients for a very strong preparation program,” said Professor Helen Harrington, who was integral to developing and implementing the new program.

The proliferation of new technologies couldn’t help but influence exploration of new methods of educating teachers. Professor Magdalene Lampert was a pioneer in the use of interactive media to prepare students for the real-world problems they would face as teachers. Recognizing that the information prospective teachers have to learn about teaching is complex, and learning bit by bit is difficult to apply in practical situations, Lampert noted that “high level practical learning can occur when novices are presented with problems that are complex and difficult, if this is done in contexts where they have the opportunity to think and talk about such problems with others who have different levels of experience.” This style filters through to their teaching practice, where the teacher leads an engaged discussion rather than simply handing down knowledge and marking students’ answers as correct or incorrect. Lampert also advocated for technology in teacher preparation as vital to new teachers’ knowledge and understanding of how to use emerging technologies in the classroom.

In addition to the new Prechter Laboratory for Interactive Technology, the Center for Highly Interactive Computing in Education (hi-ce) was a resource for tackling the problems of technology in schools through perspectives of research, curriculum building, assessment, home and community engagement, and professional development for teachers.

Evelyn Whitner was a veteran teacher of 25 years when she first used hi-ce’s air quality and water quality curriculum with her 7th grade students at Detroit’s Taft Middle School in the mid-’90s. She noted that the interactive program had changed everything, from the physical setup of her classroom to the ways students communicated with her and with each other. “If they have a question or concern, they don’t have to come directly to me. They can ask someone in their group,” she said at the time. Whitner also said that this allowed some students to perform as “captains,” and that tackling “real” (as opposed to textbook) problems helped them engage with the material.

Not all reform movements of the ’90s prioritized finding new and more effective methods of learning; as education came under fire for what was seen as mediocre testing results, policies around teacher certification became a topic of debate. Some legislators and policymakers suggested doing away with state certification altogether and allowing districts or even individual schools to set their own standards. Others defended certification as necessary for protecting the learning and safety of students, as well as reducing variation in the quality of teachers from one district to the next—that is to say, where a child lives should not determine whether they have access to good teachers. Reformers, including leaders at the SOE, also emphasized the interest of the state in perpetuating a well-educated citizenry. Without certification, they said, there would be no way to assess whether teachers had any knowledge of their subject matter or the skills necessary to ensure a successful classroom.

The debate continued into the new century, especially as teachers and administrators searched for ways to meet the standards of the 2001 No Child Left Behind legislation. “A rigorous and professional system of initial and continuing education of teachers is essential,” wrote Dean Deborah Loewenberg Ball in a 2005 response to a New York Times editorial decrying the reform movement and teacher training programs. “Teachers deserve nothing less than first-rate training for the complex work we ask of them. Without this, and the major investments it will demand, dreams of school reform will remain nothing more than vain hopes.”

For its part, the SOE continued to make those major investments to realize the dream of education reform, both by launching new initiatives and expanding successful programs. Joining the Holmes Group helped establish SOE as a national convener of researchers on teacher education. Soon, the university’s leadership in reform would bear fruit in the Teacher Education Initiative (TEI), which then grew into TeachingWorks. Since 2004, TeachingWorks has focused on improving teacher preparation and establishing a professional standard for starting a career as an educator, with an eye toward addressing the inequities facing so many Black, Latinx, and Native American children, and children living in historically marginalized and underserved communities.

The school also explored a new method of teacher preparation with ties to the training of medical professionals. Beginning in 2005, professors Bob Bain and Elizabeth Moje introduced Clinical Rounds, a concept initially focused on students who were training to become social studies teachers. Over the next decade, though, the program expanded to include prospective teachers in mathematics, science, English language arts, and world languages. The Clinical Rounds system rotated teacher candidates through a series of clinical environments, observing five different teachers who each excel at particular instructional skills and each hold their classes in schools within different socioeconomic contexts.

The school’s research centers also proved valuable hubs of innovation. The Center for Improving Early Reading Achievement (CIERA) launched in 1999, was a consortium of researchers from five universities: the University of Michigan, University of Virginia, Michigan State University, University of Minnesota, and University of Southern California. The work of the school’s established research centers, notably the Center for the Study of Higher and Postsecondary Education (CSHPE), also continued their innovative work.

“Direct experience is more powerful than vicarious learning,” said Patricia King, who was director of CSHPE from 2003 through 2006. King, who is also the author of Learning Partnerships: Theory and Models of Practice to Educate for Self-Authorship, believes that a focus on subject-matter expertise at the expense of decision-making skills and applications of understanding does a disservice to teacher education students. Partnerships with school districts and other organizations, though, can provide interdisciplinary learning in diverse contexts. King also advocated for networked communities, which would include colleges and universities across different regions of the state or country to create more seamless communication and collaboration toward shared goals. One such network sponsored by SOE in the mid-’00s was the Oakland Writing Project, a site of the National Writing Project in collaboration with Oakland Schools and Adrian College. The National Writing Project program sought to create “intellectual homes” for practicing teachers and create a learning community that would last beyond the four-week intensive program.

The SOE’s partnerships with local schools have taken a number of forms throughout the 100-plus year history of teacher education at Michigan, from short-term projects aimed at achieving defined goals or research outcomes to longer-term collaborations that improve teacher preparation as well as classroom learning. Two robust partnerships established in the last decade continue to set a new standard for collaborations between K-12 schools and teacher education programs.

The Mitchell Scarlett Huron Teaching and Learning Collaborative is a partnership with Ann Arbor’s Mitchell Elementary and Scarlett Middle School (with the recent addition of Huron High School expanding the scope of the partnership through 12th grade). Students, teachers, families, and university partners (including SOE students, staff, and faculty) teach and learn together as part of a cohesive learning community. The collaborative supports a continuum of professional learning where all educators and administrators commit to studying teaching practices in ways that lead to improved student achievement.

The Detroit P-20 Partnership, launched in 2018, offers an integrated preschool through grade 12 education system on a single campus, research-based curricular offerings, and services to meet the needs of students and families. The scope of this partnership also includes one of the most exciting innovations in teacher education: the Teaching School, located within the public K-12 School at Marygrove. Further building on the benefits of the medical education model, the Teaching School provides a professional environment in which teacher education students (interns and student teachers) and new, certified teachers (residents) are carefully and consistently supported by veteran teachers and other education experts. Twenty-nine SOE students have already been interns or student teachers at Marygrove and four SOE graduates are currently completing their residencies.

Like the SOE’s vital partnerships, the teacher education curriculum has continued to evolve. In the past several years, new courses, certificates, and endorsement opportunities have emerged to meet the needs of students preparing to be educators in a diverse range of classrooms and school systems.

- In 2019, the Social Justice Transformative Educator Institute introduced inclusive curricula and practices to incoming secondary education students.

- The International Baccalaureate (IB) certificate prepares future educators to assume roles in IB schools around the world.

- The popular English as a Second Language endorsement, which includes a summer experience with students in the Summer ESL Academy at Scarlett Middle School, became available to students in all teacher preparation programs.

- The SOE introduced a Trauma-Informed Practice certificate, which focuses on understanding and applying trauma knowledge to inform teaching practices and understanding and enacting roles in interprofessional collaboration.

The demand from educators outside of the SOE to be equipped with knowledge in the area of trauma-informed practice led to the creation of a free, online course on the topic, launched in October 2021. The course is part of a suite of online courses focused on inclusive teaching and learning.

Driven by a commitment to prepare educators who are well-equipped to do the complex work of teaching, the SOE is continuously improving its own teacher education programs and sharing research and practices with other teacher preparation programs across the country.