Before DEI “Year 1”

Generations of SOE community members have long worked to advance diversity, equity, and inclusion on campus and in the field of education

The University of Michigan has long considered itself a champion of the critical social causes that have arisen over the years. Yet we know that the university has not always acted on the side of justice, and has sometimes espoused ideals not backed up by its actions. In an effort to chart a course toward meaningful engagement with the issues of representation, anti-racism, and lack of opportunity that have long existed but which have come into greater focus over the past decade, in 2015 the university launched its five-year Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) Strategic Plan.

The SOE was the first unit on campus to submit a school-specific plan to the university’s administration. The Education Diversity Advisory Committee developed a multifaceted proposal to provide the SOE community with a framework and charge to prioritize, develop, and implement actions necessary to realize the commitments outlined in the school’s diversity, equity, and inclusion statement. The statement began: “At the School of Education, our effort to study and improve educational practice is inseparable from our determination to develop more effective and socially just systems of education. This mission is grounded in our commitment to promote diversity and to advance equity and inclusion.”

The plan that was submitted in 2015 may have said “Year 1,” but it wasn’t the first time the SOE community had championed diversity, equity, and inclusion—both within its own walls and in the broader context of educational policy and practice. The centennial milestone provides an opportunity to explore several of the projects, people, and initiatives that built the foundation for what the SOE community now calls dije (Diversity, Inclusion, Justice, and Equity).

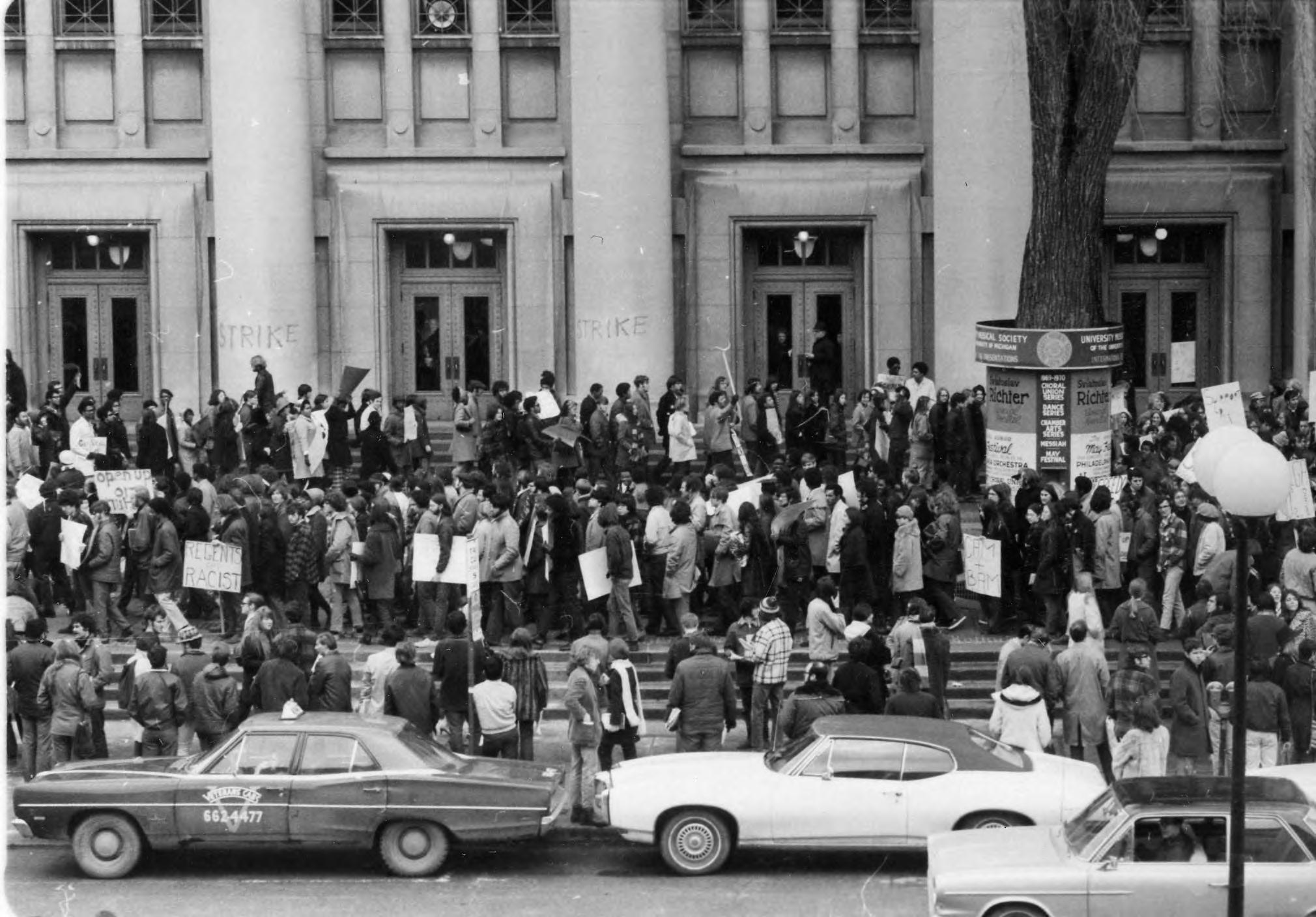

Efforts to increase diversity at the SOE have not always grown out of official policy, but have often been initiated by students and faculty members. In a committee meeting in 1969, the student Black Caucus demanded the school achieve 20 percent Black enrollment and 20 percent representation in the faculty. While the faculty agreed to work toward these goals, which were reaffirmed during the campuswide Black Action Movement strike in 1970, the school ultimately fell short of this goal. However, because of this effort, the SOE did significantly improve its numbers of Black students and faculty throughout the ’70s, rising to 16.5 percent non-white students and 13.3 percent Black students by 1982, both of which were the highest among U-M schools and colleges at the time. Today, the SOE student population is 34 percent Black, Indigenous, or people of color (BIPOC) across all programs and 27 percent BIPOC across the faculty population. Despite these gains, there is still significant work to be done to diversify both the SOE community and the field of education at large.

Coinciding with the student activism of the late 1960s and early 1970s, SOE students won representation on school committees, thanks to the activist group Students for Educational Innovation. This group also hosted conferences and workshops on urban education, women in education, and other issues of the day.

Student activism also helped launch major initiatives beyond the Ann Arbor campus. Inspired by then-Senator John F. Kennedy’s speech at the Michigan Union only a few weeks before his election as the 35th president of the United States, SOE graduate student Judith Guskin (MA ’61, PhD ’70) began excitedly discussing the potential for students to improve lives in developing countries. After publishing a note in the Michigan Daily asking for letters of support for a student-led international aid program, the enthusiastic response led Guskin to start a petition drive to gain official backing for their project. This in turn led to a sit-down lunch with Senator Kennedy the weekend before his election. “I gave him the petitions and he looked into my eyes,” Guskin said in a 2010 interview with the Daily. “And he listened, he really was attentive.” Kennedy promised Guskin immediate action on their proposal after the election, and in the summer of 1961, the Peace Corps was born. Guskin served in the first program and went to Thailand. After her return to the U.S., she worked to further develop the global Peace Corps program.

President Kennedy’s famous speech was not the only time inspiration for change came from guest speakers. Dr. Foster Gibbs, superintendent of the Saginaw Public Schools, emphasized a need for districts to “grow their own” BIPOC teachers since not enough people of color were entering the field of education. The school instituted the Preferred Admissions plan with LSA to encourage more minority first-year students to become teachers.

Members of the faculty, too, have had profound impact beyond the school. Wilbur J. Cohen, who taught at U-M for 28 years and was the dean of the SOE from 1969 to 1978, came to the university from Washington, DC, after helping to establish the Social Security program, and later took a hiatus from campus to serve in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. As dean, he focused SOE policy around educational opportunity and access, and his tenure saw the launch of major equity initiatives including the Urban Program in Education and the Program for Educational Opportunity.

Beginning in the 1950s, Black faculty members blazed trails and contributed to the school’s research and instructional eminence. Professor Alvin Demar Loving, Sr., the first Black teacher in the Detroit Public Schools, began his career at U-M as an associate professor in 1956 as one of the inaugural 16 faculty members of UM-Flint, and the only Black scholar among that number. Loving joined the SOE’s Executive Committee in 1969, and the following year became the first Black faculty member to become a full professor at U-M. That year, Dean Wilbur J. Cohen also named Loving Assistant Dean of the SOE. In that role, Loving improved the school’s work on urban education and expanded teacher training programs in urban schools.

Professor Betty Mae Morrison (AB ’52, AM ’65, PhD ’66) joined the U-M faculty in 1970 after a career as a medical technologist and research psychologist. As a Black woman—and, for much of her 22 years at the School of Education, the only woman to attain the rank of professor— Morrison helped open the traditionally male fields of research and statistics to women.

Morrison’s research in the area of educational psychology was cited in a 1973 report by the United States Commission on Civil Rights during the Commission's investigation of the barriers to equal educational opportunities for Mexican Americans in the public school systems of the southwest. When Morrison passed away in 2008, she established a scholarship fund for doctoral students pursuing quantitative research that will continue to support new generations in perpetuity.

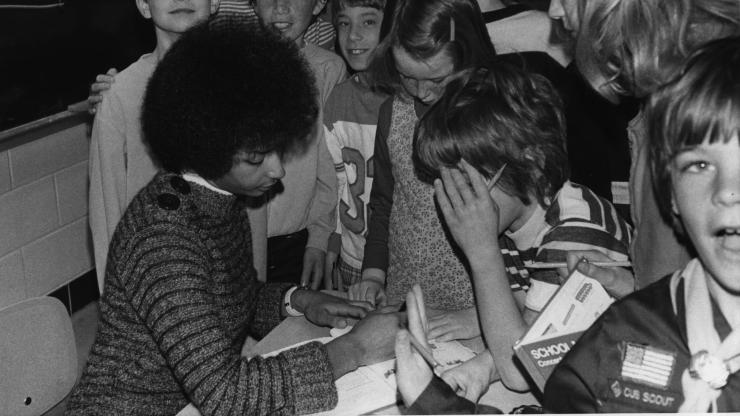

In the same year that Morrison joined U-M, Charles Moody joined the SOE faculty as professor of education and director of the Program for Educational Opportunity, a federally funded program designed to support school desegregation over a tri-state area through consultations with school systems, conferences focused on training and policy, and a publication series. Moody would continue to be a leader in diversity efforts at the school for more than 25 years. Shortly after joining the SOE he founded the National Alliance of Black School Educators, which continues to serve children, teachers, and administrators more than 50 years later. At U-M, Moody became Director of the Project for Fair Administration of School Discipline in 1975, Director of the Center for Sex Equity in Schools in 1981, and Vice Provost for Minority Affairs in 1987.

When Moody was promoted to U-M Vice Provost for Minority Affairs, he launched King/Chavez/Parks College Days, part of a state-led initiative to increase the presence in higher education of students from historically marginalized communities. The program focused on junior high school students, helping them understand not only the preparation needed before college, but also the broad array of careers they might not have considered. The program also used a variety of current technology to practice the skills necessary to navigate a rapidly changing world.

Prominent faculty continued to shape equity efforts throughout the decades that followed. Before joining SOE, Arnetha Ball (AB ’71, MS ’72) enjoyed a teaching career spanning 25 years, during which time she also founded the Children’s Creative Workshop, an early education center for students from diverse backgrounds. During her time at U-M, from 1992 to 2001, Ball’s research focused on the writing of Black students, including the use of African American Vernacular English (AAVE) and teaching to the strengths of students from diverse cultural backgrounds. She continued her work at Stanford and remains an active researcher.

Professor Cho-Yee To, who served on the faculty from 1967 to 2003, challenged his undergraduate students to think critically about race, multilingual education, and socio-emotional learning through the creation of a student journal. Participation in the journal was required for students in To’s Education 392 class. The undergraduate journal, which was published under several different titles, featured essays on the contemporary issues facing teachers. An introductory note to the Winter 1994 edition of T.E.A.CH.: Tomorrow’s Educators Accepting the Challenge, noted that “future teachers cannot consider teaching as the only challenge they face in education,” charging its readers to become “careful observers” of the effects that parental involvement, extracurricular activities, multicultural education, and technology would have on their lives and those of their students. To, who is now professor emeritus, also established a travel scholarship fund to enable SOE students to study in China and Hong Kong.

In 1998, the SOE and the School of Social Work, in collaboration with other campus organizations, offered the first MLK Children & Youth Program. Professor Henry Meares, who continues to direct the event, utilizes storytelling, group projects, discussions, music, and art, to help participants explore contemporary issues regarding race, class, justice, and diversity. In its 23 years, the program has served over 9,600 K-12 students and engaged hundreds of U-M students, faculty, and staff.

As the new millennium began, Dean Karen Wixson formed a task force to construct a “vision for the school’s role in diversity, to make sure it is incorporated in the school’s research and curriculum, and devise ways to communicate this vision to the larger community.” The task force included both junior and senior faculty members and students. The legacy of that task force may have set the stage for the emergence of dije more than a decade later: current Dean Elizabeth Birr Moje served on it while an assistant professor.

Professor Percy Bates, Director of the Programs for Educational Opportunity, noted that, after this cultural audit in 2001, “we found out that while the school was not necessarily openly hostile to minorities, there was some feeling that we needed to do a lot more.” One concern was that the lack of diversity among students and faculty could be self-perpetuating—that if prospective students and visiting faculty did not see other people of color, Bates said, “they might not see much that represented them or their concerns, which would just reinforce the recruitment problem.”

This led to the creation of a Social Justice Initiative, which made several recommendations to the executive committee during the 2005–06 year, including the establishment of a Social Justice and Education Studies concentration in the PhD program, inclusion of readings and coursework relevant to the experiences of historically marginalized people, and the recruitment of senior scholars of color, especially those whose work directly addresses social justice themes.

The early 2000s also saw additional initiatives from student activists. In 2003, a group of nine graduate students had gathered to share their concerns about the culture and climate of SOE, forming the Social Justice and Educational Equity Graduate Student Committee.

Sonia Deluca and Alina Wong, two doctoral students in CSHPE on the committee, coordinated a new course that grew from the group’s work; the seminar called Critical Issues in Social Justice and Education was first offered in fall 2003. The committee was also responsible for hosting a Social Justice Initiative seminar celebrating the 50th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education in 2004.

“In our concern for the climate at the School of Ed, we kept coming back to the fact that our experiences as graduate students did not reflect those of a socially just community,” Deluca said at the time. “We did not feel adequately prepared to enact change in education for the promises of a diverse democracy.”

Deluca received the university’s Leadership Tapestry Award, given to students, staff, and faculty in recognition of those “instrumental in promoting social justice, multiculturalism, and diversity locally, regionally, nationally, or internationally for the creation of a more enriched and socially just world.” She is now engaged in this work as Associate Vice Provost for Educational Equity at Penn State University.

Penny Pasque, another graduate student involved with the committee, said that student involvement and energy “helped some faculty, staff, and students conceptualize the work [of social justice] more broadly.”

“The initiative has effectively served as a broad introduction to ‘what could be,’” said Bates, in 2006. He added that the seminars and guest speakers “challenged all participants to look hard at program designs, hiring practices, teaching methods, and new possibilities.”

Dean Deborah Loewenberg Ball led a strategic assessment of the SOE in 2010. The large group of faculty, staff, and students who crafted the report identified the school's two core commitments as the study and improvement of educational practice and the advancement of the twin imperatives of diversity and equity.

“We live in an increasingly diverse and deeply inequitable society,” says the report. “So, on one hand, we seek to develop ways to work to support and make usable the positive educational and social resources of diversity. On the other hand, we also aim to redress the inequities that result from social, cultural, and economic differences. Diversity is both an asset and the source of deep societal and educational inequities, and we think it is crucial that our work take active and deliberate account of both.”

The three broad ways to advance equity and diversity articulated in the 2010 report are evident in the DEI plan submitted in 2015: “in developing who we are, in defining what we work on, and in the ways in which we organize and practice our organizational culture, policies, and practices.”

The SOE community continues to track and assess progress annually through a combined report/plan made available at soe.umich.edu/dije.

Dean Elizabeth Moje says, “We must both celebrate the courageous people who have advanced social justice through education, and acknowledge when we have fallen short of our ideals. As the urgent work of anti-racism and social justice continues, this community takes seriously our responsibility to live the principles of dije and help create a more just and equitable world.”