Investigating the Science and Art of Education

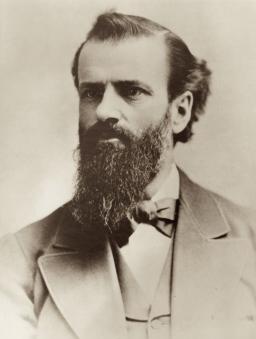

The University of Michigan has been a leader in education research since even before the foundation of its School of Education. When William H. Payne was named Chair of the Science and the Art of Teaching at the University of Michigan in 1879, he became the first faculty member at any American university to assume a professorship dedicated fully to the study of education.

At the time, teacher training was usually conducted in “normal” schools. Payne’s appointment led to intense debate about the role of universities in education research and teacher training at the university level. But U-M soon emerged as a leader in the formal scholarship of education in the U.S.

Since then, the level of scholarly productivity in the SOE has been consistently among the highest for education programs nationally. The research conducted by SOE faculty, staff, and students has demonstrated scholarly impact and informed the work of countless PreK-20 practitioners and policymakers. The Institute for Scientific Information ranked U-M first in the field of education among 100 research universities for citations per paper between the years of 1981 and 1993, spotlighting the high impact of research conducted by SOE faculty. “Ranking number one in citations is an important indicator of the quality of scholarly activity in the SOE and across the university,” said Cecil Miskel, who served as dean of the school from 1988–98.

Today, the SOE is ranked #1 by the Center for World University Rankings in education and educational research based on the number of research articles in top-tier journals.

Although far from a comprehensive record of all the research generated at the SOE, this issue of Michigan Education provides an opportunity to reflect on the roots of education research at U-M and the shifts that have inspired new areas of focus for well over a century.

Emergence of education research in the U.S.

The debate about the value of the study of education did not end with Payne’s appointment. Three early, ardent supporters were Payne, Burke Aaron Hinsdale—who was the second appointee to the Chair of the Science and the Art of Teaching—and a young philosophy professor named John Dewey.

In 1889, Hinsdale asked, “Why should an institution that exists for the sake of investigating the arts and sciences leave its own peculiar art neglected and despised?” The three men built communities of like-minded educators while sharing their observations and thoughts with a growing audience.

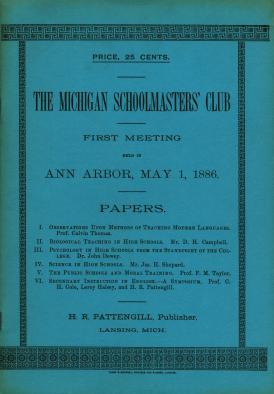

From 1884 to 1894, while at U-M, Dewey took an active role in high school accreditation visits and helped develop the Michigan Schoolmasters’ Club, an organization that sought to strengthen the connections between secondary and university instructors. It was at club meetings that Dewey first discussed his developing concepts of education. At the first official meeting, Dewey presented “Psychology in High Schools from the Standpoint of the College,” arguing that psychology should be taught in high schools as a means of making the mind more open to new ideas for the student’s own self-awareness.

Later in his career, Dewey recalled how his time at U-M formed his educational philosophy: “It was there that my serious interest in education was aroused. I have never ceased to be grateful that my first connection was with a state university in the middle-west. I learned there something of the deep significance of the relations between educational institutions and the social communities which they serve.”

School as laboratory

After Dewey’s departure in 1894, the years leading up to and immediately following the founding of the SOE in 1921 were characterized by a growth in research inquiry on topics such as child development, measurement and testing, school administration, hygiene, and comparative models of international education. Researchers were excited about the opportunities presented by model schools, where faculty from both the SOE and other units could make scientific observations. To this end, U-M’s Department of Education arranged with the Ann Arbor Board of Education in 1912 to allow observation in Ann Arbor High School and W.S. Perry Elementary School.

In 1923, one of the school’s first grants was awarded to Stuart A. Courtis to study the effects of heredity, maturity, and training on the success of around 2,500 children in Detroit Public Schools. Courtis had been the Director of Educational Research for Detroit Public Schools (1914–1919) and Director of Instruction and Dean at the Detroit Teachers College (1920–1924). Courtis’ interest in educational measurement—a field then in its infancy—was shared by generations of SOE researchers. In 1938, Courtis wrote, “After thirty years of study my conclusion is that no single test and no battery of tests of any type or description yields unambiguous information about the quantities educationalists wished to measure.” Never abandoning his fundamental belief in the potential of testing to improve education, Courtis was among the earliest of U-M’s scholars of educational measurement.

A contemporary of Courtis, Guy Montrose Whipple’s seminal two-volume Manual of Mental and Physical Tests stood as the exclusive reference of psychological testers for nearly 20 years. Whipple, a psychologist, contributed to the emerging scholarship around gifted education, mental testing, reading instruction, and vocational education.

William Clark Trow began his career at Michigan in 1926 and proved a foundational figure in the field of educational psychology, making the SOE a hub of research for the emerging discipline. Trow wrote 15 books, each filling a different need and reframing the conversation around educational psychology. His book Educational Psychology, published in 1931, was the first true text in the field. One of Trow’s major contributions was to shift focus away from more surface explorations of senses, perception, and memory to foreground the psychological nature of the problems teachers had long faced. In 1977, his Handbook of Teaching Educational Psychology became the standard text for teaching educational psychology at the college level.

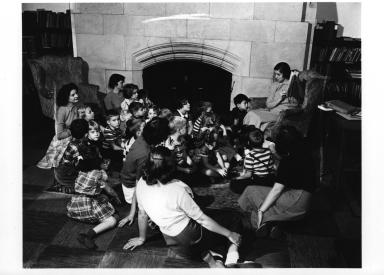

Clifford Woody, who was on the faculty from 1921 through 1948, wrote: “Extended experiments dealing with teaching practices in their natural situations are needed. One who is familiar with educational psychology knows that the great body of data, upon which our psychological laws and principles are based, were developed in the laboratory and in the absence of actual teaching situations.” This sentiment was shared by other educational researchers who petitioned the university to build a “laboratory school” on the campus, similar to those that had begun to spring up at other prestigious universities.

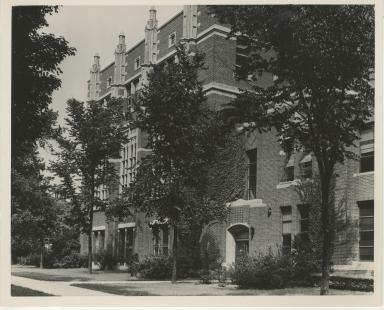

Much of the research that took place over the school’s first half century was performed at University High School, which opened its doors in 1924 with funding from the Michigan Legislature. The new University Elementary school opened in 1930, though plans for a larger building were curtailed by the Great Depression. Together, the two schools were envisioned as a laboratory to explore the best theories of education and conduct research on child development and learning.

Shifting national priorities give education research new direction

From the late 1930s through the early 1950s, economic depression and war resulted in a period of diminished educational research across the country. However, in 1957, the launch of the Sputnik satellite inspired a new emphasis on education in the fields of mathematics, sciences, and foreign languages. With additional national funding and national attention in these areas, enrollment in the SOE increased dramatically and space was at a premium.

By 1962, the school had 107 research projects in progress and 59 active faculty members. This postwar growth led to pressure on the school’s staff, laboratories, and classrooms, which prompted a reexamination of the school’s resources and priorities. The need for space, coupled with the City of Ann Arbor’s economic decision to build a new high school, led to the closing of the University Schools.

Even after the closure of University High School and University Elementary School in the late 1960s, the SOE continued to partner with school districts, colleges, and community organizations to unite academia and educational practice. These relationships have stimulated advances in the field through the establishment of collaborative environments for research in education. The evolution of these research-practice settings is evident in the current Mitchell Scarlett Huron Teaching and Learning Collaborative and the Detroit P-20 Partnership, begun in 2011 and 2018, respectively.

Just as testing and assessment had fascinated faculty around the time of the school’s founding, the SOE would continue to contribute greatly to the field. An influential researcher through the 1950s and 1960s, Professor Frank Womer had a particular interest in testing and the construction of assessments. In 1967, he began a four-year leave from the university to lead the new National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), the first national effort to compare student performance. NAEP soon became known as the “Nation’s Report Card.” Womer believed in the potential of good testing, done right, to help educators improve their work. But he lamented the rise of teachers “teaching to the test” and, though long since retired before the era of No Child Left Behind, objected to the 2001 law’s punitive practices when schools failed to meet its test score standards.

In 1956, professor Wilbur J. Cohen, another preeminent researcher who shaped national policy, joined the university faculty after 22 years as an adviser to presidents Roosevelt, Truman, and Eisenhower. Cohen was among the original architects of the Social Security Act of 1935 and served in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. Given the designations “The Man Who Built Medicare" and "Mr. Social Security," Cohen’s leadership of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare resulted in landmark legislation in the fields of mental health, education, vocational education, medical assistance, and social security reform.

Cohen’s teaching and research were directly related to his policy work on problems of economic security. In 1969, he returned to Michigan to become dean of the SOE. His leadership of the school reflected his continuing concerns about educational opportunity and access, affirmative action and equity, and early childhood education. Additionally, through his efforts, the SOE became the first university department to offer formal academic training in educational gerontology—an area of research and practice for which the school became internationally recognized.

In 1957, the school formally became a leader in the study of higher education. Funded by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Center for the Study of Higher and Postsecondary Education (CSHPE) was established. The center’s purpose as defined by founding director Algo Henderson was “to serve those having or expecting to have leadership roles in colleges and universities.” The investment allowed the school to add faculty and provide graduate and postgraduate research fellowships.

The center arose from two cultural factors at play in the 1950s. Sparked by the passage of the GI Bill in 1944 and the Truman Commission’s recommendation in 1950 that higher education should be made available to all secondary school graduates, the 1950s saw a boom in college and university enrollment. This coincided with a trend toward universities becoming increasingly dependent on federal funding for research in the postwar period, which brought with it more stringent reporting requirements. The CSHPE was one of three centers founded to address the burgeoning need for trained administrators and the rapidly changing needs of higher education policy. The center was tasked with preparing leaders for an entirely new environment and crafting a more scholarly and professionalized approach to higher education. They were, in effect, forging a new discipline.

Centers and institutes lead national, collaborative efforts

Grant-funded research thrived in the SOE’s centers and institutes. Broadly speaking, centers carried out systematic research and development activities aimed at improving education from preschool through college. These were hubs for interdisciplinary teams across the U-M campus and inter-institutional research teams across the state and nation.

The Program for Educational Opportunity (PEO) was a Race Desegregation Assistance Center funded under Title IV of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Beginning in 1970, PEO helped school districts promote equal educational opportunity for students. To help districts transition from segregation to integration, PEO offered needs assessment, Equal Employment Opportunity planning, training, and consultative services to districts in Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin. Working in affiliation with PEO, the Center for Sex Equity in Schools offered free resources for school districts to remove sexist and discriminatory practices, create fair counseling and career education techniques, and encourage community involvement and support.

The first director of PEO, Professor Charles D. Moody, joined the SOE in 1970. He also directed the Project for Fair Administration of Student Discipline from 1975-80 and the Center for Sex Equity in Schools from 1981–87. Moody founded the National Alliance of Black School Educators, which was originally conceived as a way for Black school superintendents to share concerns, develop a resource pool, and form an organization. NABSE exists today as “the nation’s premiere nonprofit organization devoted to furthering the academic success for the nation’s children—particularly children of African descent.” Moody also directed and participated in numerous major workshops and conferences to promote equity in education. In 1987, Moody became vice provost for minority affairs for U-M. He served in this post until 1993, when he became executive director of South African Initiatives and vice provost emeritus for minority affairs.

The Bureau of Accreditation and School Improvement Studies (BASIS) in the SOE was the sole statewide accreditation agent for Michigan high schools. The BASIS program of research emphasized the role of accreditation as a tool for school improvement. Through data collection, organization, and analysis, researchers involved with BASIS sought to relate school reform to knowledge about local, state, and federal policy initiatives. BASIS was also the co-sponsor of the annual Michigan School Testing Conference, which was founded by professor Frank Womer. Through a generous gift from Womer, the school holds an annual conference in his memory that features experts in the field of educational assessment.

During Marvin W. Peterson’s leadership of CSHPE from 1976–96, the center’s focus evolved from its professional development roots to become known nationally and internationally for its research and policy expertise. The National Center for Research to Improve Postsecondary Teaching and Learning (NCRIPTL) was established in 1986 under the auspices of the Office of Educational Research and Improvement. With co-sponsors across campus, CSHPE faculty members led the center’s scholarship and dissemination efforts. Their research focused on five aspects of college learning environments that can affect learning outcomes: classroom learning and teaching strategies, curricular structure and integration, faculty attitudes and teaching behaviors, organizational practices, and the use of emerging information technology. Established as a five-year program, the center served 2,800 colleges that had undergraduate teaching as their primary mission.

As part of the scope of NCRIPTL, professors Jan Lawrence and Robert Blackburn completed a large-scale national survey of 4,240 professors that culminated in their book Faculty at Work: Motivation, Expectation, Satisfaction. The study was unparalleled in its variety of institutional settings, scope of disciplines, and coverage of the many facets of faculty work.

A common theme among many of the school’s prestigious centers was the integration of research and practice. This approach to education practice and research was aptly summed up by Dr. Carl Berger during his term as dean of the SOE from 1983–88. “We can’t divorce research from what’s happening in education,” Berger said. “Our research will be problem-oriented and applied, more like engineering than basic science.”

Supported by grants from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, the Center for Education Improvement through Collaboration (CEIC) developed pilot projects to improve teaching curricula in grades K-12. “University faculty often complain that their research findings are not implemented in the schools, but when teachers assist in the research, the results are carried back to the classroom immediately,” said Jay L. Robinson, CEIC director, in 1987. CEIC’s efforts grew from an initial focus on literacy programs to include an internship program for secondary school science teachers in U-M laboratories; programs in environmental studies; a humanities program linking the arts, natural sciences, social sciences, and local cultural resources; and a program to evaluate the decision-making processes in local school settings.

Similarly, the Center for Research on Learning and Schooling (CRLS) was founded in 1985 to provide a focal point for research on issues of K-12 education. With a mission to generate empirical research in schools that promoted the cognitive and social development of students, CRLS provided a space for interdisciplinary scholarship and collaborative research by faculty and students throughout the campus. CRLS was also a vehicle for collaboration between field-based educators and academic partners.

In the 1990s, Combined Program in Education and Psychology faculty Phyllis Blumenfeld, Jacquelynn Eccles, Stuart Karabenick, Martin Maher, Carol Midgley, Scott Paris, and Paul Pintrich, along with their graduate students, were in the vanguard of psychologists redefining theory and research regarding the relationships among motivation, self-regulation, and epistemology. Their research yielded new measures of these constructs and reshaped interventions designed to enhance academic learning.

Research revitalizes the school and demonstrates institutional expertise in literacy, assessment, and emerging technologies

As the challenges facing the field of education changed, so too did the research focus of the school. The revitalization of the SOE following the extreme budget cuts of the 1980s led to a research boom in the 1990s, when new faculty members Annemarie Palincsar, J. Gary Knowles, Joseph S. Krajcik, and Pamela Moss joined prominent faculty including Anne Ruggles Gere, Phyllis Blumenfeld, Valerie Lee, Paul Pintrich, and Karen Wixson. Although federal funding had also been in a long period of decline, corporate and organizational funding was on the rise. A 1996 report showed that grants and contracts had increased from $3,125,000 to $6,141,000, or by nearly 100 percent, over the previous six years.

Literacy and language acquisition was a major research interest throughout the 1990s. Professor Arnetha Ball’s research focused on the cultural contexts of literacy, including its use in job applications, diary entries, letters, rap songs, and other formal and informal contexts. “I want to understand the characteristics of those environments that are conducive to learning for different groups,” she said. Ball spoke with youth at community-based organizations in Palo Alto and San Jose, California, and in Detroit and Pontiac, Michigan, to form a picture of the modes of learning and expression that occur outside of schools. “Schools are indeed looking for ways to see students become more successful, yet the schools seldom look to community-based organizations as resources,” she noted.

During a time when many states were making significant efforts to rethink what school can and should be, Professor David Cohen led a five-year project, based in California, South Carolina, and Michigan to study how each state’s education reform policies were implemented in schools and their effects on students, particularly those from lower-income households. “We wanted to see what states’ actions made a difference in what teachers do and how these reforms played out in schools, especially schools in which children come from disadvantaged homes,” Cohen said. Among the significant changes taking place in those classrooms in the mid-’90s, Cohen and his team found “a greater use of real literature, real books written by real authors” instead of basal readers. There was also a shift away from ability grouping and a more open dialogue in the classroom—“kids talk more, teachers listen more.”

Professor Annemarie Sullivan Palincsar’s scholarship transformed the field of cognition, learning, and instruction by developing a program of research based on the belief that the purpose of education is to facilitate children’s ability to think, reason, problem solve, and transfer learning to novel situations. She launched a new field of instructional intervention called Reciprocal Teaching (RT) in which students and their teachers co-construct the meanings of shared texts through dialogue. In particular, she designed RT to support students who struggled to learn with text so that they could flexibly and dialogically use the comprehension strategies documented among successful readers.

Professor Anne Ruggles Gere focused her work on the language of peer-response writing groups and how discussions within these groups help the writers develop a sense of audience. In one project, she explored the lives of women in book groups around the turn of the 20th century and how involvement in such groups was both a form of self-education and an instrument for adapting to the rapidly industrializing and modernizing world.

Professor Elizabeth Sulzby further contributed to the SOE’s research on reading as a pioneer of “emergent literacy,” studying childhood communications such as scribble and invented spellings as these transition into more standard reading and writing.

Professor Elfrieda Hiebert, co-author of the landmark 1985 book Becoming a Nation of Readers, turned her attention a decade later to exploring new approaches to early literacy. “We’re attempting to focus and build on what kids already know about reading so we’re not taking a deficit perspective,” she said. Noting that part of learning to read is coming to recognize through repetition different patterns of letters and the sounds they create, Hiebert describes language as a system with predictable rules. “I want to let kids in on the secrets of written language.”

The research activity surrounding reading and literacy led to the birth of a new center in 1997. Led first by Hiebert and later by Professor Joanne Carlisle, the Center for the Improvement of Early Reading Achievement (CIERA) was a consortium housed at the SOE whose purpose was to discover theoretical, empirical, and practical solutions to persistent problems in early reading. Researchers accomplished this through a broad range of research inquiries, including analyzing how increasingly diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds of America’s students interacted with existing models of teaching reading and exploring how culturally familiar songs can work with children’s existing knowledge to aid in literacy. One crucial aspect of CIERA’s mission was making sure its research could be easily accessible to teachers, policymakers, and other researchers, so all CIERA documents were made available free to read online, and nearly all were downloadable.

The 1990s also saw a renewed interest in assessment, continuing a research tradition going back to the first faculty of the newly formed SOE in the 1920s. As traditional assessment methods were criticized for testing students’ knowledge in a way that was both one-dimensional and out of context, there arose a desire for systems to test more complex thinking, as well as for testing that was more developmentally appropriate for younger learners. But there was resistance to the emerging new methods of assessment as too subjective and difficult to measure against a meaningful standard.

Professor Samuel J. Meisels of the Center for Human Growth and Development developed a system for early childhood assessment called Work Sampling, which won praise as a framework for teachers to review student work such as crayon drawings against a national standard using developmental benchmarks and other interrelated criteria. The Work Sampling System proved to be a more reliable predictor of a child’s progress through the school year than more traditional measures.

Professor Pamela Moss argued for a broader definition of validity in educational assessment to expand the ways in which assessment might be used to support teaching and learning. Informed by research discourses outside educational measurement (hermeneutics, sociocultural studies, critical theory), she argued for the value of alternative ways of drawing and warranting interpretations of learning; tracing the consequences of assessment practice, including the identities and positions afforded teachers and students; and conceptualizing assessment as an interacting element of larger educational system. Among the outcomes of this work was a multidisciplinary collaboration among scholars in psychometrics and sociocultural studies, sponsored by the Spencer Foundation, that resulted in the edited volume, Assessment, Equity, and Opportunity to Learn.

It was also during this time that evaluating uses of emerging technology in the classroom became an urgent need. Professor Magdalene L. Lampert advocated for the benefits of technology in teacher preparation for its ability to present the complex problems of teaching while also providing a platform to think through and discuss them within the classroom. And, as teachers “teach what they are taught,” bringing such technologies into their own classrooms further allows their students to develop “tools for analyzing and connecting information in personally meaningful ways.” “Interactive multimedia technology can support a new image of the teacher as one who provokes and guides students’ thinking and problem solving, rather than one who merely ‘tells’ knowledge and judges answers to be right or wrong,” Lampert said.

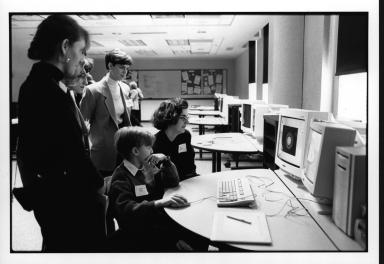

The SOE was an early adopter of many new technologies of the 1980s and 1990s, exploring the full potential of computers, networking, and “multimedia” in classrooms. These new technologies offered fresh approaches to problem solving, innovation within teacher training and teaching practice, and adapting to meet the evolving needs of modern students in an increasingly connected world. The Prechter Laboratory was a key component of this research and training, a centralized hub of technology in an era before students could regularly carry a computer in their backpacks (or indeed in their pockets).

By the end of the 1990s, several new centers had emerged, funded by the U.S. Department of Education and the National Science Foundation to conduct some of the most vital educational research in the nation, bolstering the SOE’s reputation as a leader in the field. These included the Center for Learning Technologies in Urban Schools, which was dedicated to building case studies on reform strategies, addressing inequity, and studying “actual effects” of interventions in teaching, and the National Center for Research on Policy and Teaching, a project studying the relationships between teachers’ opportunities to learn, teachers’ practice, and students’ achievement.

New research foci for the dawn of the 21st century

Just as an influx of new faculty in the late 1980s shaped the course of research at the school for the next decade, new researchers joining the SOE in the late 1990s similarly recast the research environment for the new millennium. These new faculty members included Deborah Loewenberg Ball, whose research interests included teacher education and math education, and who would serve as the dean from 2005–2016; Gary D. Fenstermacher, an expert in the fields of philosophy of education and teacher education, moral dimensions of education and educational theory, and policy analysis in teaching and teacher education; Carla O’Connor, who focused on urban education and social psychology of education; Virginia Richardson, whose focus was on teaching pedagogy, including teacher beliefs, decision making, and change; and Nancy B. Songer, whose research explored science education curriculum, learning trajectories, and educational technology.

As the 21st century began, the school introduced a new mathematics education program, ushering in a new focus on mathematics research areas. From 1993 through 2000, the entire mathematics education faculty had changed, and the new leaders were keen to improve instruction not just through new curricula but more effective practice. “That piece—making a curriculum work, figuring out what you really do during class to get kids to learn—is really what all of us study,” said Deborah Ball, part of the new wave of faculty that also included professors Hyman Bass, Patricio Herbst, Magdalene Lampert, Vilma Mesa, and Edward Silver.

Professors Ball, Bass, and Herbst collaborated on the Mathematics Teaching and Learning to Teach project, which sought to understand the work of teaching and how the teachers themselves may influence student learning paths. “There are lots of professional development programs that educate teachers, but to a large extent they are based on an analysis of curriculums,” Hyman Bass said. “The best way to learn what the dynamic of a teacher’s interaction with kids looks like is to actually observe it.”

“This is a very unusual math ed group in that we are all very connected to mathematics as a subject field,” Ball said. “All of us are people for whom mathematics as a discipline is a central thing we work on and think about. But we think about it in relation to teaching children.”

The mathematics education faculty was subsequently joined by Professor Maisie Gholson, a Black feminist mathematics education scholar whose research has focused on the learning and development of mathematical knowledge and skill among Black children.

CSHPE brings a critical lens to diversity, equity, and inclusion in higher education

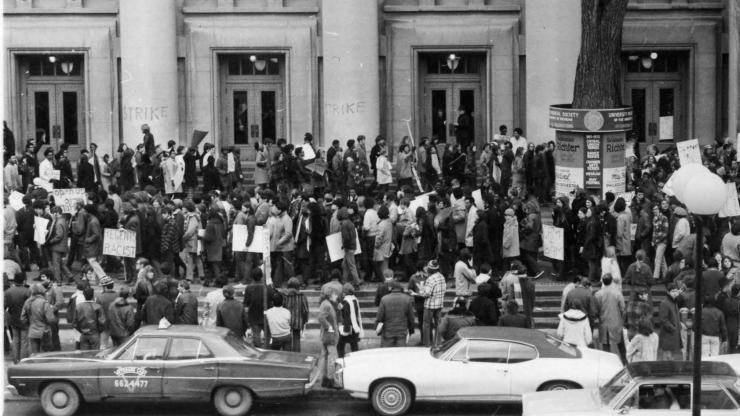

U-M’s Center for Social Solutions estimated that at the height of student activism in the 1960s, one in five student protests demanded an end to racial discrimination on campus. By the 1980s and 1990s, many colleges and universities had implemented admissions policies and multicultural programming aimed at increasing the diversity of the student body. Soon there was backlash against affirmative action practices. The future of such policies was to be decided, in part, by major court cases, including two involving U-M.

CSHPE faculty and staff contributed their expertise on diversity, equity, and inclusion in higher education systems to state and national governmental agencies and higher education institutions. Professors Deborah Faye Carter, Sylvia Hurtado, and Edward St. John examined topics such as admissions, financial aid, student retention, curricula, and campus climate to illuminate the effects of policies and propose actions that could better serve students of color.

In the late 1990s, CSHPE professors Eric Dey and Sylvia Hurtado provided evidence to the federal courts that U-M’s race-conscious admissions policies were justified by their educational benefits. Their work demonstrated that a “racially and ethnically diverse student body has significant educational benefits for all students, nonminority and minority alike.” Although the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against the university in 2003 in Gratz v. Bollinger, they upheld the consideration of applicants’ race in Grutter v. Bollinger. Dey and Hurtado subsequently co-authored Defending Diversity: Affirmative Action at the University of Michigan with other social scientists and university leaders involved with the case.

Research projects examine controversial legislation

The new century also introduced new opportunities and challenges in the form of No Child Left Behind (NCLB), a 2001 education reform law. The law provided for a number of new research grant opportunities, but also included new assessment guidelines for both teachers and students that many education researchers found more punitive than constructive.

Professor Joanne Carlisle assisted the Michigan Department of Education in securing a Reading First grant in 2002, part of the No Child Left Behind legislation, and conducted a statewide evaluation of the funded product. Though the act was contentious, Carlisle saw the Reading First program as having more potential benefit than some other sections of the law, in part because it provided support for teachers to receive professional development to better help students learning to read. Professors Elizabeth Sulzby and Deanna Birdyshaw also received an Early Reading First grant to work with seven of the lowest-performing school districts in the nation, to help preschool teachers expand their students’ oral language skills and basic understanding of reading and writing.

Professor Steve Raudenbush, who had long held that programs aimed at improving teaching needed to be tested scientifically, found the school evaluation systems put into place as part of NCLB were “scientifically indefensible.” His research was published in the monograph Schools, Statistics, and Poverty: Can We Measure School Improvement?, which was distributed to 10,000 educators by Educational Testing Service, a nongovernmental organization that constructs some of the tests used to evaluate performance under NCLB.

Raudenbush’s research complemented that of a contemporary project by Professor Lesley Rex, who studied the effects of NCLB’s mandated accountability measures on teachers and their students. She and research assistant Matt Nelson found that “increasing external accountability measures on teachers is counterproductive when they compete with teachers’ internal accountability,” and that such measures do little but frustrate teachers and lower morale.

Professor Donald Peurach, who did his doctoral work under Professor David Cohen in the 1990s and joined the SOE as a faculty member in 2011, studied large-scale efforts to improve classroom instruction in ways responsive both to the educational ambitions of reformers and to the accountability demands of such policies as NCLB. Peurach and colleagues have advanced theory and evidence showing that sustained (if incoherent) policy dynamics pressing to improve educational quality and to reduce disparities have driven (and continue to drive) the evolution of schools, districts, and networks as educational systems that organize, manage, and improve the day-to-day work of students and teachers in classrooms.

Even in the midst of these challenges, the early 2000s set the stage for meaningful reform through the emergence of inquiry- and project-based education, which have grown into central themes of SOE faculty research. The Center for Highly Interactive Classrooms, Curricula & Computing in Education (hi-ce) was an interdisciplinary group of science educators, computer scientists, psychologists, scientists, and literacy and learning specialists dedicated to inquiry-based curricula, learner-centered technologies, comprehensive professional development, and administrative and organizational models. This group included Joseph Krajcik, Ron Marx, Barry Fishman, Elizabeth Moje, Betsy Davis, Phyllis Blumenfeld, and Elliot Soloway.

One of the hi-ce projects, the Curriculum Access System for Elementary Science (CASES) offered a number of teacher resources, including 4- to 8-week unit plans focused on a particular theme or question. It was also one of only a very few websites designed for new teachers. Teachers who used CASES praised its activities, ease of use, and inclusion of background information to ensure teachers really understand the material they are teaching. Betsy Davis, who created the grant-supported software, advocates for inquiry-oriented science as a way to address American students’ lagging scores in science. “By engaging in inquiry-oriented science, the teacher and the students all slow down and get into a concept in depth,” Davis said. “Teaching for understanding and inquiry-oriented teaching go hand in hand.”

A new generation of collaborations at the heart of engaged public scholarship

Karen Wixson, dean of the SOE from 2000–2005, said, “As higher education champions the vision of ‘an engaged university’ working for the public good, we’re becoming an engaged school of education, working collaboratively to address real-world problems in public education.” This is a vision that future deans Deborah Ball and Elizabeth Moje championed and advanced.

Beginning in 2004, the SOE launched an effort to reform its teacher training programs, with a focus on developing a more practice-oriented curriculum for learning to teach. This initiative was the foundation for an organization that reaches far beyond U-M: TeachingWorks. Initially, faculty and practicing teachers worked together to identify a small set of instructional practices that are crucial for beginning and early career teachers to be able to do well, and a number of topics and ideas that they should understand and know how to teach. TeachingWorks has flourished and connected educators and educator preparation programs around the country as they continue to develop and share knowledge about learning to teach.

Originally housed in the SOE, the Center for the Study of Black Youth in Context (CSBYC) was funded by the National Science Foundation in 2008. Professors Tabbye Chavous, Robert Sellers, Stephanie Rowley, Carla O'Connor, and Robert Jagers partnered to study ways families socialized their children around race and to examine the influence of various types of parenting on child academic and social outcomes. This work depended on the cultivation of collaborative relationships with local communities to help inform, improve, and create practice and intervention approaches for promoting youths’ positive social and educational outcomes. CSBYC provided—and continues to provide—training for early scholars and students around skills necessary to do research and practice with diverse populations of children in diverse community and school settings.

Long gone are the days of the “laboratory school,” but two robust partnerships with public school districts keep a strong connection between the university and local teachers, students, and administrators: the Mitchell Scarlett Huron Teaching and Learning Collaborative and the Detroit P-20 Partnership.

In 2011, the Mitchell Scarlett Huron Teaching and Learning Collaborative emerged out of a discussion about how the SOE and the Ann Arbor Public Schools could address pressing needs of both organizations while positioning K-12 students as the most important beneficiaries of all the work done in the partnership. Ann Arbor Public Schools needed to address the achievement gap in its two lowest SES and lowest-achieving schools relative to other district schools, and the SOE needed a school site where teaching interns could learn, alongside expert educators, how to teach diverse students, and where faculty and staff could implement and refine the newly reformed, practice-based elementary teacher education curriculum. A decade later, numerous projects have grown out of the partnership, and the addition of Huron High School has expanded the scope of the work. The shared understanding that work must be mutually beneficial, respectful, and always child-centered has assured the collaboration’s longevity.

The Detroit P-20 Partnership, announced in 2018, involves the SOE, Detroit Public Schools Community District, the Kresge Foundation, Starfish Family Services, and the Marygrove Conservancy in a collaboration to create a truly outstanding “cradle to career” campus in northwestern Detroit. The K-12 public school on the campus, called The School at Marygrove, opened in 2019. The project- and place-based curriculum centered in community-based and social justice-oriented learning opportunities isn’t the only remarkable thing about this school: it is also home to the first Teaching School, which includes a supportive model for teaching interns interested in urban education, a novel three-year residency program for novice teachers, and opportunities for expert educators to continue to grow in the profession.

In 2014, the SOE launched the Center for Education Design, Evaluation, and Research (CEDER) to create a gateway for schools, nonprofit organizations, researchers, other universities, and companies looking to connect with experts at the SOE. Through CEDER, dozens of new collaborations have formed. The results have been innovative curricula for K-20 classrooms, new professional development opportunities, and educational grant and award programs.

The research landscape at year 100

In fiscal year 2020, the SOE had $8,897,188 in research expenditures. Today, with 55 active grants at the SOE, the breadth of the work reflects the diverse expertise among the faculty.

Although federal funding for research at higher education institutions has declined, support from foundations committed to the improvement of educational practice and policy has propelled the work of SOE researchers forward. Significant funders include the National Institutes of Health, National Science Foundation, Knight Foundation, Ford Foundation, Spencer Foundation, William T. Grant Foundation, Carnegie Corporation of New York, the George Lucas Educational Foundation, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, and the James S. McDonnell Foundation.

Recent foundation grants have advanced important work in diverse areas of education research:

- In 2017, professors Patricio Herbst and Chauncey Monte-Sano each received grants from the James S. McDonnell Foundation for their research in the fields of mathematics education and inquiry-based education in history and social studies, respectively, representing the first grants to SOE from the McDonnell Foundation since 1996.

- The W.K. Kellogg Foundation also returned to the higher education sector, supporting Nell K. Duke’s Great First Eight curriculum development research, with a goal to develop, pilot, and refine 0-8 interdisciplinary, developmentally appropriate, culturally responsive curriculum.

- Pamela Moss and Carl Lagoze (School of Information) received a Lyle Spencer Research Award to Transform Education for work on infrastructures that underlie education research—systems of technical resources, social structures, modes of communication, standards, routine practices, rights of access, and incentives—that shape how knowledge is produced and used. The award supports participatory co-design of a prototype exploring elements of “living” community-centered knowledge commons, intended to encourage collective action across conventional silos in education research.

- Beginning in 2020, the Spencer Foundation supported Camille Wilson’s Urban Learning and Leadership Collaborative, a research-practice partnership that unites Detroit community members with university researchers to create innovative, inquiry-based solutions to challenges identified by community residents.

- TeachingWorks received a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to establish a Teacher Preparation Transformation Center.

In addition to continued scholarly contributions in areas that have defined the expertise of the SOE for decades—such as teacher education, literacy, instructional technologies, higher education, educational psychology, mathematics instruction, school leadership, and policy—new research teams and centers tackle emerging topics with fresh approaches, which will no doubt redefine our coming century.

Robust programs of research advance scholarship that aim to dismantle racist and oppressive educational practices, policies, and systems; deconstruct barriers to educational access and opportunity for children, youth, and adults; and present new paths toward equity and inclusion. In addition to ongoing work across the SOE, the addition of four faculty members—Charles H. F. Davis III, Jamaal Matthews, Rosemary Perez, and Ebony Elizabeth Thomas—in 2020 and 2021 enhanced the school’s scholarship in these areas.

A number of SOE faculty members bring a global perspective to their research. These foci include cross-cultural comparisons in college admissions systems, language learning, and cognitive processes of students. Also included is investigation of the impact that experiences with violence, asylum, and peace and justice processes have on students' participation in school and society.

Currently, over 10 percent of the active projects investigate aspects of education affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. These projects range from a study of the personnel turnover in early childhood education centers to the effects of the pandemic on college enrollments. Among the projects that are informing the path forward in the wake of the pandemic is a suite of high-quality, free, online professional development modules for Michigan’s teachers and school staff focused on inclusive teaching and learning.

In 2020, Professor Camille Wilson launched the Community-based Research on Equity, Activism, & Transformative Education Center—the CREATE Center—in order to advance the collaborative efforts of equity-driven scholars, education advocates, and activists to conduct or leverage research in the service of transformative public education for children, families, and communities impacted by the injustices of systemic racism and poverty.

“We consistently hear calls for improved education systems, better-prepared practitioners, and policies that make sense for children, families, educators, and employers. The way to achieve all of those demands is to start with solid research that engages the communities that the work is meant to serve, relies on scientific methods of inquiry, and challenges norms that currently lead to inequity and injustice,” says Dean Moje.

The SOE community heads into this next chapter hand in hand with the people who work in education and those served by educational systems. Acknowledging that research is only as meaningful as its reach into practice and policy, the future of research relies on the continued growth of respectful, mutually beneficial partnerships and a commitment to center the experiences of learners and educators in all aspects of the work.