Title IX at Michigan

Three Education alumnae tell their stories of fighting for equity for women on campus

When it became federal law nearly 50 years ago, Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 promised more equitable opportunities for women in education, from grade school through grad school. Although it immediately forbade discrimination on the basis of sex for any educational program or activity receiving federal funding, the full implications of the law and its applications would take several decades to unfold. For this centennial issue, we spoke with three School of Education alumnae who played a role in implementing Title IX at the University of Michigan and nationwide.

Jeanette Lim Esbrook: Enforcing Title IX

Jeanette Lim Esbrook (BS ’62, TeachCert ’62) graduated from U-M in 1962 with a degree in chemistry, adding a teaching certificate because teaching, at the time, was considered one of a limited number of career options for women with science degrees. After pursuing graduate studies in medical genetics at the University of Wisconsin, however, the political and social movements of the late 1960s and early ’70s set her on a new path. “The Women's Movement and the Civil Rights Movement changed my career focus, and I decided to go to law school, which I did in 1972,” Esbrook recalls. Before beginning law school, Esbrook was hired to help implement affirmative action measures at the University of Delaware. “Back in the early ’70s, a group of women discovered that the Department of Labor had contract compliance executive orders requiring universities with federal contracts including the University of Delaware to take affirmative action to include women and minorities in its faculty hiring practices,” Esbrook says. “That job was my introduction to the federal government's civil rights requirements. The two E.O.s were my introduction to regulatory and statutory requirements similar to Title IX, which eventually was passed in 1972.”

After receiving a JD and passing the bar in 1979, Esbrook was hired as a member of the general counsel’s office at Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW), a federal government agency that was later divided into the Department of Education and the Department of Health and Human Services. At the time, HEW’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR) was preparing final regulations for the implementation of Title IX over intercollegiate athletics. Esbrook was assigned to work on the policy. The final policy document setting out Title IX requirements was published on December 11, 1979. The OCR had received several Title IX complaints against university athletic programs alleging unequal athletic opportunities for women.

With the policy published, Esbrook and her team were tasked with investigating the numerous complaints. This required traveling from Washington, DC, to explain the policies to the department’s 10 regional field offices with responsibilities to investigate complaints filed in their regions. “As the policy was so new, we had to do a big training,” Esbrook recalls. “HEW had a training center in Denver, Colorado, where the investigators from the 10 regional offices of the Office for Civil Rights came, and I was part of the team that taught the investigative approach to attorneys and investigators from the regions so that we could start dealing with numerous complaints we’d already received.”

At the time, women’s teams were under the administration of the AIAW, not the NCAA, and none of the women trainers had experience with the NCAA. After training was completed, teams were named, and Esbrook found herself a member of the team investigating complaints at the University of Michigan, among other schools.

In addition to intercollegiate athletics, Esbrook was assigned to develop policy for investigating what became known as “sexual harassment” complaints. In the early 1980s these were new types of complaints made by students and received by OCR, as well as the Justice Department, Department of Labor, and the Equal Employment Opportunities Commission (EEOC). In 1983, as a policy attorney in the Office of Civil Rights in the recently reconfigured Department of Education, she wrote the first internal OCR guidance instructing the department’s regional offices how to investigate these new complaints. “That’s how the term ‘sexual harassment’ originated,” Esbrook says, “for better or worse.” She now feels the term “sexual” may have distracted from the “harassment” or bullying aspects of the complaints and caused misunderstanding. “Looking back, maybe there was a better term we could have chosen, but that's what we chose.”

Eventually Esbrook’s and others’ work on sexual harassment policy had an influence broader than expected. “The Title IX sexual harassment policy established while I was working as the policy director in OCR formed the basis of the anti-harassment policies based on disability and based on race,” she says. “It was one of the few areas where sex discrimination was the leader in establishing a civil rights policy. Title VI and race were typically at the forefront in terms of how we learned to deal with discriminatory issues, but this harassment issue was one of the areas where Title IX and sex discrimination led.”

Her career in government would later find Esbrook advocating for Title IX protections as a senior litigating attorney at the Department of Justice. In 1996, she was a member of the team litigating a major 14th Amendment and Title IX case against The Citadel, an all-male public military college in South Carolina, which, concurrently with the Virginia Military Institute (VMI), had been taken to court by plaintiffs seeking the admission of women. Both the Citadel and VMI received public funds.

“Even when the Naval Academy, West Point, and the Air Force Academy opened their institutions to women, these two institutions were still limiting admissions to men,” Esbrook says. While the Citadel had offered to create a separate, similar institution for women, Esbrook compared this arrangement to Brown v. Board of Education, which ruled against “separate but equal” schools on the grounds that they could never truly be equal. “If you got a degree from and wore the Citadel ring, you had access to the power structure of South Carolina,” Esbrook explains. “If you wanted to get into politics in South Carolina, or become a bank board member, or a big corporation board member, if you were a Citadel grad, you became a member of a network that opened doors.” These were aspects of the Citadel experience, Esbrook says, that “you could not replicate in a so-called separate but equal institution for women.” Even as the DOJ team including Esbrook was presenting the Citadel case in the U.S. District Court of South Carolina, the Supreme Court of the United States handed down a decision in the parallel VMI case before them that settled the matter, and both the Citadel and Virginia Military Institute were compelled to open their enrollment to women.

“We were actually in court the day the Supreme Court came down with the VMI decision, and our judge said, ‘Guess what, folks? The Supreme Court has spoken, and I'm asking you to retire and work out a corrective action plan for the Citadel to enroll women,’” Esbrook recalls. She added that the Supreme Court had ruled against VMI using the same argument the DOJ team had been employing in the Citadel case: that the established prestige and networks of the schools would not carry through to any newly created institution for women.

Now retired from government, Esbrook serves as Vice President, Legal Affairs for the Clearinghouse on Women’s Issues (CWI). Because of her deep expertise on policies surrounding sexual harassment on college campuses, Esbrook testified before the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs of the Office of Management and Budget during the Trump administration, challenging proposed rule changes to Title IX that many felt weakened protections for complainants. “Basically, the Trump administration and Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos felt that the regulations and the policy on sexual harassment did not provide the person who is accused sufficient due process rights,” Esbrook says. “So they retracted a group of policies that have been promulgated since the early ’80s, and they wrote a prescriptive and limiting regulation that required due process implementation to the point where universities’ investigative processes were turned into quasi courtroom-like proceedings. I recognized from years of university experience that the culture of the university isn’t suitable for courtroom-like disciplinary procedures. Universities are places of education and a less formal discipline process which can include attention to due process and fairness can be consistent with a university’s learning environment.

“The result of the revised regulations has made sexual harassment investigations more difficult for universities to deal with, and puts a toll on the person who wants to file a complaint. It's difficult enough for an individual who has been sexually harassed to come forward, and with the new sexual harassment regulation, it was even worse. So that's what informed my decision to help with the Clearinghouse statement.”

Esbrook hopes the Biden administration will put a hold on implementing the new regulations and instead conduct a listening tour of universities and advocates for both survivors and the accused, hearing their concerns to find a better way forward in addressing sexual harassment complaints.

“This is a serious matter, and we need to know that universities and school districts are safe places where students are free from bullying and harassment,” Esbrook says. She emphasizes the difficulty, well before the Trump-DeVos policies, of victims of sexual assault finding justice. She cites the scene in William Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure, written around 1603, in which the seemingly pious Angelo offers to spare Isabella’s brother’s life if she sleeps with him; when she threatens to expose him, Angelo says simply, “Who will believe thee, Isabella?” “Even back then, William Shakespeare knew that it's very difficult for victims of sexual harassment to be believed,” Esbrook says. “It's a very difficult psychological trauma, and there's been a culture of disbelief.”

Sheryl Szady: Leader of the Jacket Gals

Sheryl Szady (BSEd ’74, TeachCert ’74, AM ’75, PhD ’87) says the thinking when Title IX passed in 1972 was that the law was primarily intended to open graduate school programs to women. “Medical schools, hospital administration programs, had very few, if any, women in them,” she says. “I don't know that it was one of the primary goals to get women’s varsity athletics on an even footing with men’s athletics.” But as the guidelines for implementing Title IX started to take shape, it became clear that addressing college sports would be essential.

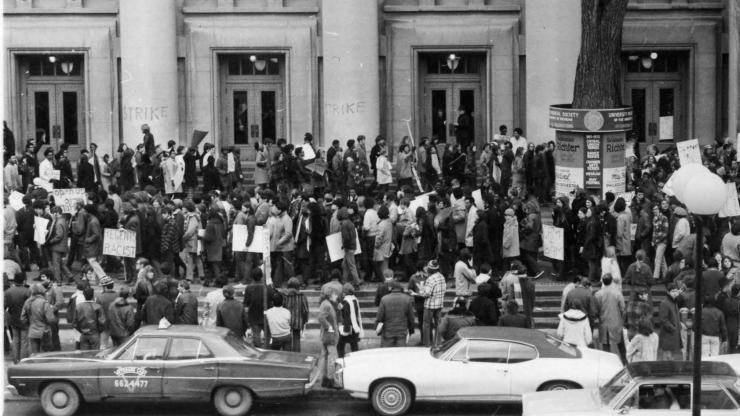

The Title IX legislation passed while Szady was a student-athlete at U-M, but the guidelines for implementation were not released until 1975, a year after she graduated. As such, there was no clear guidance on how the law might support her fight to institute varsity women’s sports at Michigan against considerable resistance. Yet through perseverance and a bit of good fortune, she got her message across.

As student leader of U-M’s club sport field hockey team, Szady was responsible for calling the varsity coaches of universities throughout the state to arrange a schedule of matches. “They would pretty much dictate what was the best for them,” Szady says of the varsity squads the Michigan women’s team played in the early 1970s. But in 1973, Szady found that the coaches who had graciously granted the Michigan club a game in years past were now denying her requests. “Finally, the Eastern Michigan field hockey coach called me back and said, ‘Sheryl, just to let you know, we decided at the SMAIAW [a women’s organization parallel to the men’s NCAA] that nobody was playing Michigan this year. We're basically excluding you until Michigan steps up to create a varsity program.’”

In addition to some logistical hurdles to meeting Association of Intercollegiate Athletics for Women guidelines for establishing women’s varsity sports at U-M, Szady and her allies faced catch-22 scenarios when they approached then-athletic director Don Canham. Canham would ask Szady about the teams they played, she says, but was unsatisfied with her answers. To be a varsity team, Canham said, the women would need to play bigger schools. But to play those schools, Michigan women would need varsity program status. “So he’d say, ‘you're so close, you've got to grow these club sport programs, grow your numbers, your competition level, your skill level. You need to win,’” Szady recalls. At one point the athletic director did offer the women’s teams $2,000, to assist 12 club teams.

“I actually thought, we need more money so that we could travel and hire coaches. I was approaching the Office of Development because they would mail out a card every year to alumni asking for money for different programs,” Szady recalls. She asked for a line in the donation request specifically for the women’s sports teams. This request moved the philosophical question of supporting athletics for women up the university administration to Henry Johnson (SOE faculty 1970–72), the then-Vice President of Student Affairs. While a meeting with President Robben Fleming was not granted, this would start Szady down the fateful path to her meeting with the university’s Board of Regents.

Szady put together a presentation outlining what was required for Michigan women’s varsity athletics under the AIAW guidelines—notably not referencing Title IX. She would have five minutes to make her case before the regents.

After watching a group of students who were presenting before her be dismissed hastily, Szady was not optimistic, but to her surprise, after the presentation, Fleming reviewed her materials and asked Marie Hartwig (who had led the women’s sports program before the women’s and men’s Physical Educations departments merged and would be later be named the first associate director of athletics for women) to begin exploring whether varsity women’s sports could be implemented at Michigan.

“The committee members were all positive. This is something that the [women’s physical education faculty and staff] couldn’t do because if they fought for women’s athletics, they’d be fighting against Don Canham and Paul Hunsicker and they would risk getting fired,” Szady says. That spring and summer, an advisory committee met to recommend the six strongest women’s club sports that would gain varsity status. In August 1973, Hartwig called Szady to let her know that Fleming had directed her to begin women’s varsity athletics in September 1973. Szady quite aptly described the timeline as “incredibly fast for the university to move on anything.”

The initial lineup of women’s varsity sports included field hockey, volleyball, basketball, swimming and diving, tennis, and synchronized swimming. “Because of the turnaround, we looked a lot like the club program of previous years in terms of who we played, but where we used to borrow or steal cars (as we would say) to jam into them, now we had university vans,” Szady says. She mentioned that the players for the first time also received meal money, $1.50 for home games and $3.50 on the road.

“We still were taking our own uniforms home and washing them. You were issued one for the season and you were responsible for showing up clean,” she says.

Before graduating in 1974, Szady lettered in field hockey and basketball. But as she stayed on to complete a master’s degree, she found that varsity awards had not been considered for the female varsity athletes. “I asked the Advisory Committee, ‘And where are our varsity letters? Where are our varsity awards?’ And everybody said, ‘Don't even go there, you got your varsity programs,’” she recalls. “But we represent Michigan!” This would be the beginning of Szady’s second major fight for women’s athletics, and this one would take considerably more than a single summer to resolve.

Szady found herself on the Board in Control of Intercollegiate Athletics’ committee—appointed by Don Canham—to review the schedule of varsity awards for the student-athletes. “I'm sure he wasn’t really happy in the end because while I surveyed all the women’s teams and came up with a schedule of awards that blended well with the men’s, the question of the Block M proved contentious. I asked to stipulate the same Block M be used on awards for women and men, and this was not popular at all.” The issue was initially put to a vote by the board, but Canham “didn't like” what he saw, so he tabled the issue.

Two days later, they sent out letters to the former male letter-winners from the president of the all-male Letterwinners M Club, and a letter from Bo Schembechler and then-basketball coach Johnny Orr, that said, among other things, “how can you let women have the same M that you bled and sweated on the fields of Michigan for?” The letter included the home addresses of Szady and the other board members. “I just received tons of letters, like, think of a Kroger brown paper bag two-thirds filled with the nastiest letters from Michigan letter-winners, well-placed people. ‘How dare you ask for the same Block M?’”

But as the next board meeting loomed, Szady also began receiving correspondence of another sort. “I started getting letters from some educators who said, ‘you're doing the right thing. You deserve the Block M,’” Szady recalls.

Though she would not discover this until afterward, Szady received a significant late-inning boost from an unexpected source. “The night before the meeting, Al Ackerman, Detroit’s Channel Four sportscaster, said, ‘I got wind of these letters to the Letterwinners,’” Szady recounts. “And he said, ‘I will never report another Michigan athletic score if Michigan doesn't give women the Block M.’”

In Szady’s telling, this set off frantic activity among Fleming and the executive officers, who cut short a retreat for two vice-presidents who returned to Ann Arbor with instructions to make sure women received the Block M.

Before the meeting, Szady, who did not yet know of the power hitters in her lineup, was called in to Canham’s office. “I sat down, and he said, ‘What do you want?’ And I said, ‘the same Block M for men and women.’ He said, ‘you aren't going to get that.’” Canham reportedly offered a variety of alternatives including a blue M, a script M, and others. He repeated his question. “In retrospect, I should have said I want four tickets on the 50 for life,” Szady jokes. “I said, ‘I want the same Block M, and I'll take my chances with the board,’ because clearly he wasn’t going to negotiate.” As she turned to leave, “I realized that the alum members and some of the faculty members of the board were standing in the office behind me. It seemed quite confrontational, even though I hadn’t seen them going in.”

After Szady’s proposal was reviewed, the majority of the Board of Regents voted in favor of granting the women student-athletes Michigan’s famous Block M, the same as the men’s. The only holdout has since established scholarship funds for every varsity sport, both men’s and women’s.

The day after her victory with the regents, Szady was photographed by the Ann Arbor News holding a sweater with the Block M she had earned, a photo which graced the front page of the paper’s next edition, “right next to a picture of Henry Kissinger.” But when, a year later, she received a package from the university with her varsity award, she discovered a letter jacket with “this little square orange M on it.”

No one then at the university was willing to take up her fight, but when Szady returned in the 1980s to pursue her PhD she renewed her efforts. “I met with every athletic director to tell them that these were the wrong Ms and not only for the current women, but these past women,” who had played for Michigan in the years since 1973–74, she says. Finally, when Jack Weidenbach became athletic director in 1991, he agreed that “it was time to change.” Women student-athletes began receiving the same Block M as their male counterparts immediately, but still the past letter recipients held what Szady describes as “the wrong M.”

Finally, in 2016, her first meeting with incoming athletic director Warde Manuel proved a breakthrough. Manuel agreed it was time to provide the iconic Block M to all the women who had earned one playing varsity sports at Michigan, from 1973 to 1991.

From there, the challenge was logistics. Szady had provided a list, with contact information, of 900 women who should receive new jackets, but the Athletic department would not tell her who had ordered one, citing privacy. “I'm the one that gave you the contacts!” she laughed. Eventually, Szady was told that 120 women had signed up for new jackets, a number that pleased the department but not Szady. So she began networking, asking her contacts to reach out to anybody they knew from their teams, and so on. This resulted in an initial order of 647 letter jackets. Eventually, Szady managed to contact all but 29 of the 900 women.

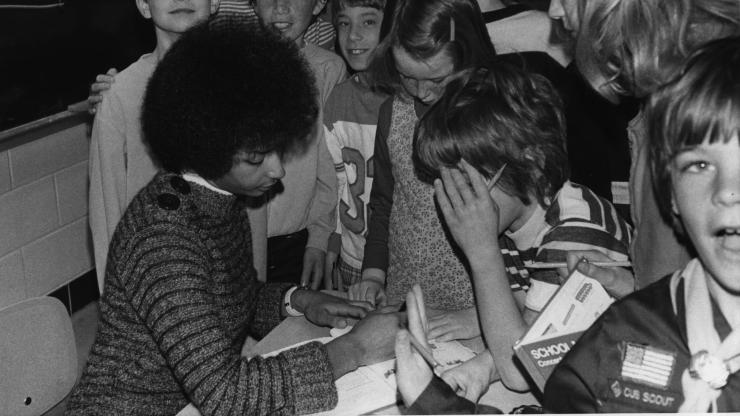

A Facebook group was formed to reconnect Michigan’s women student-athletes, many of whom had lost touch in the pre-digital era. Once the jackets started arriving and the Facebook group filled with photos of the women in their Block M jackets, the former varsity student-athletes asked Szady to arrange a gathering in Ann Arbor. The “Jacket Gals” were celebrated at halftime on the field after the Marching Band program.

“It was the most magical day,” Szady says. “I'm leading the long line of Jacket Gals down the tunnel, and coming up the other way is Warde Manuel and he's cheering us on and that was nice. We are walking along the sideline as the band is playing, then heading toward the southwest corner of the field to the flagpole. And one of the neatest moments was when I turned around and saw this long line of women in their new letter jackets, and we were still coming out of the tunnel. That's how many 300 is. We line up and we're a large group along the entire goal line as we are celebrated on the scoreboard screens.” On their way off the field, the Jacket Gals climbed the section two steps where “the people are high-fiving every single one of us, and the women are just in tears because they’re finally being recognized as Michigan student-athletes.”

Carmel Borders: Michigan’s first female women’s basketball coach

Carmel Borders (AB ’72, TeachCert ’72, AM ’78) transferred to the University of Michigan in 1971, when she and her husband moved to Ann Arbor to launch Borders Books. “It turned out I was pregnant, so I did not have a traditional college experience at Michigan,” she says. “I studied hard, I took 18 hours every semester, I went summer, spring, and I was able to graduate before my kid started walking.” Borders received her bachelor’s (from LSA) and teacher certification in 1972. She would later return for a master’s degree in kinesiology, which was then a unit within the SOE, in 1978.

After completing her undergraduate work, Borders began teaching and coaching basketball at Saint Thomas the Apostle High School, where her team reached the state final four two years in a row. “When my son was about four, I would bring him to practice with me sometimes, and he always went to the games with my husband,” Borders recalls. One day, her son asked her, “Mom, can boys play basketball, too?”

Meanwhile, women’s basketball was just gaining varsity status at U-M. Borders was hired to coach the team beginning in its second season. As the program grew, Borders was able to expand the basketball schedule from its initial six-game season up to 22 games within her three years of coaching.

Recruiting players was a challenge when she started coaching at U-M, Borders says, a challenge made more difficult by the fact that her job was to begin just before the start of the season. “There were just a handful of girls who came out, and you were putting up signs everywhere, trying to get the women to come out,” she says. Borders also describes difficult training conditions, including holding practice in “the old ice hockey arena, with concrete floors that they had covered with a rubber surface.” Without professional trainers, the women on the team had to learn to tape ankles and shin splints. By the third year, Borders recalls, her team was able to practice in Crisler Arena, where they also had their games.

“The girls really played for the love of the game, and I coached for the love of the game,” Borders says, also noting that her salary at the time “wasn’t enough to cover day care.”

Coaching in those early days was further complicated by student-athletes’ academic commitments, as faculty did not always support the women’s sports programs. “I had an engineering and a nursing student on the team, and their teachers would not let them miss the exam,” Borders recalls. “So we'd have a game and we’d be short two of our best players. Oh, it's really fun to figure out the roster when you don't know who you’re gonna add in.”

Borders’ current work with her family’s charitable organization and with the Texas Book Festival stem from her experiences in the classroom. “The bottom line that became clear to me as a teacher was the importance of reading,” she says. “As a high school teacher, I did not know how to address this issue. When we developed the Tapestry Foundation in 1992, the family decided that reading should be one of the things that we focus on. So I went on a journey of learning all about how reading is taught and how we could support it as a family.”

Borders and the Tapestry Foundation decided to focus on preparation for the teaching of reading in teacher training programs as well as social-emotional learning. Borders has also served as board chair for the National Institute for Literacy, where she learned about the National Early Learning Panel and its research into the science of reading and how to teach it.