Summoning our Strength for Justice

A virtual offering for educators on trauma, wellness, and collective care

“Today is a thank-you from the School of Education to you.” Dr. Shari Saunders, associate dean for undergraduate education and educator preparation, welcomed participants to a virtual event this past July. Designed to support educators in recognizing and skillfully responding to the trauma resulting from the dual, ongoing crises of COVID-19 and anti-Black racism, program attendees included teachers and administrators from partner schools, alumni who work as education practitioners in K-12 schools, and current students, faculty, and staff of the educator preparation program.

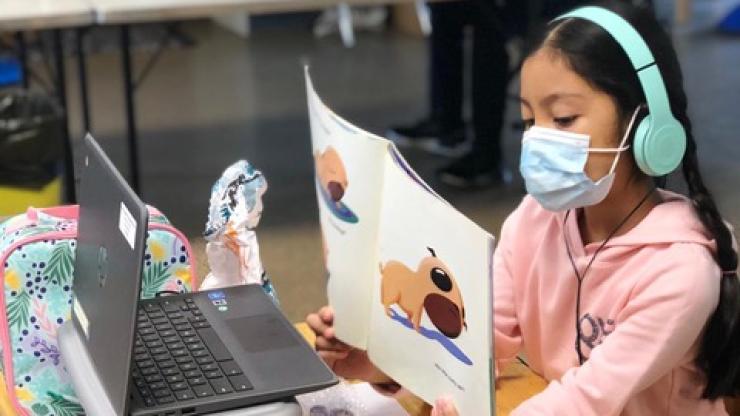

Dr. Saunders and Dr. Carla Shalaby, coordinator of social justice initiatives and community internships, conceived of the opportunity in early summer as the nation was reeling from anti-Black violence and the coronavirus outbreak. The intersection of the pandemic and the movement to dismantle inherently racist systems and structures has created a moment that calls upon educators to redouble efforts toward practices and policies that offer care and healing for youth. The series of sessions in this one-day conference honored the work teachers do to this end and demonstrated ways that teachers can be supported in this work. With a focus on healing, well-being, and collective care, the day was designed to support the mental and emotional health of educators, while modeling and teaching them ways to support the mental and emotional health of their students as they prepare for a new school year.

As SOE dean Elizabeth Moje remarked in her greeting, calls for trauma-informed and anti-racist practice among educators are not unfamiliar, nor is the school’s work in these areas. Together with the School of Nursing and the School of Social Work, U-M leaders had already collaborated on an interprofessional Trauma-Informed Practice Certificate designed to prepare professionals to serve populations affected by trauma while building supports that sustain the practitioners.

The Summoning our Strength for Justice offering for educators marked the launch of the SOE’s new Trauma Collaboratory, which is supported by the Office of the Provost.

With the goal of providing tools that can be used by teachers in the classroom and for their own self-care, the conference began with a reflection by Dr. Gail Parker, media personality, educator, and author who is both a psychologist and certified yoga therapist. Parker led participants through activities and meditations that they could try with their students, stressing the importance of cultivating one’s own mindful awareness. “You can’t teach what you don’t know,” she said. “If I’m not practicing what I’m teaching there is an inauthenticity.”

Parker shared a hopeful message about creating resilience through transformative communities of care. “We need to extend our definition of community. Community is no longer a place. It’s really a sense of connection and a sense of relationship with one another. We are called on now to create communities of the heart,” she said.

At two points in the program, Wasentha Young, the director of Peaceful Dragon School in Ann Arbor, led participants in mindful stretching. These focused breaks were refreshing and demonstrated a method of self-care that the educators could continue to employ in order to build self-care into their days.

Participants selected from sessions on topics such as healing-centered teaching and learning, key priorities in a trauma-informed approach to virtual instruction, restorative justice and community-building, and developing trauma-informed curriculum materials. These offerings allowed educators to learn from experts while sharing healing experiences with their peers.

Anita Wadhwa, classroom teacher and restorative justice coordinator at YES Prep Northbrook High School, presented with a group of high school and college students about a restorative justice model used at YES Prep. Students Kasandra Aviles (University of Houston), Beatriz Macareno (YES Prep Northbrook High School), Jose Lagunas (Washington and Jefferson College), and Leslie Lux (University of Houston) familiarized attendees with the concept of restorative justice as a way of repairing harm and transforming schools to become more inclusive spaces.

Through a youth-led approach, the presenters guided participants through the experience of forming “circles” that set community norms for respectful interaction. From that starting point, students are empowered to use the circle framework and the student-led leadership model to tackle challenging topics such as personal backgrounds and identities, school climate, and systems of power and oppression.

Nhu Do, the principal at Washtenaw International High School (WIHI) and Middle Academy (WIMA) and the program director at Washtenaw Educational Options Consortium (WEOC), presented a session titled Preparing for a Return to School: Prioritizing Healing and Collective Care. Do shared practices her school community employs in order to build a culture of collective care and inclusion.

Do discussed strategies, systems, and structures that advance collective care in her school. For example, strategies practiced in her school include maintaining consistency and routines, developing meaningful relationships, and communicating about issues that are harmful socially, emotionally, and physically. Systems that they employ include wellness surveys for students and staff and inclusive decision-making. At the time of the conference, the staff was considering how to restructure time and space to accommodate the needs of students and teachers either in person or online, with particular attention to students and staff who are vulnerable for any of a number of reasons.

Do also articulated the intersections of self care, collective care, healing, and social justice. She quoted researcher and community organizer Nakita Valerio in her presentation: "Collective care is a better stepping stone [to justice] than self-care. It addresses the fact that we're naturally cooperative. We require validation from one another to psychologically persevere and be resilient. That's where collective care offers something different. We're doing it together and trying to survive in a system that's built against us."

Alex Shevrin Venet, a Vermont-based educator, author, and professional development facilitator led a session linking trauma-informed practice to the larger work of racial justice. “Trauma is a lens, not a label,” she began. Venet asks educators to focus on fixing systems, not kids. “Resilience is located in the community, not in the individual; services and support are what creates the resilience.”

Venet provided priorities for teachers to foster through their own teaching practice: predictability, flexibility, connection, and empowerment. Trauma creates feelings of unpredictability so she recommends creating routines (which poses a new challenge in virtual learning), responding in predictable ways, and planning for dysregulation. Because trauma responses are different from moment to moment and person to person, Venet suggests checking in frequently to notice when flexibility is required. Trauma causes harm to relationships, so educators should strive to be connection-makers who develop ties among students, families, and communities. And because trauma disempowers people, Venet suggests sharing decision making, modeling consent, and dropping power struggles.

Venet adds that creating a culture based in humanity and not in systems of control has the power to disrupt causes of trauma and change how the school community functions. For example, when students and teachers demonstrate their care for each other, issues like wearing masks during the pandemic become about keeping everyone safe rather than imposing a controlling policy.

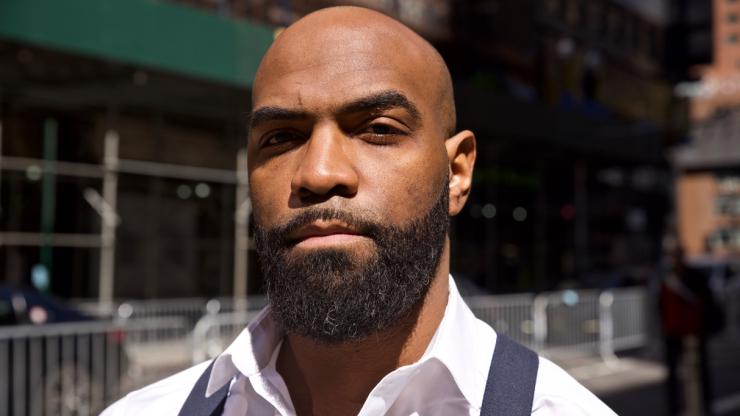

Educator and author Cornelius Minor presented a closing keynote in which he explored the question “what if instead of returning to normal, we created something better?” A return to normalcy will still leave many students and communities oppressed and traumatized by the policies, traditions, regulations, and laws that govern school spaces. Edu-culture, he remarked, is reactive, conflict-averse, and unwilling to engage in radical imagination. To confront trauma, he argues, we must confront edu-culture by actively unlearning and reinventing everything from curricula to class procedures and evaluations to interpersonal relationships. “We have to change systems so that all kids can thrive,” Minor says.