Disrupting Inequity by Investing in Education

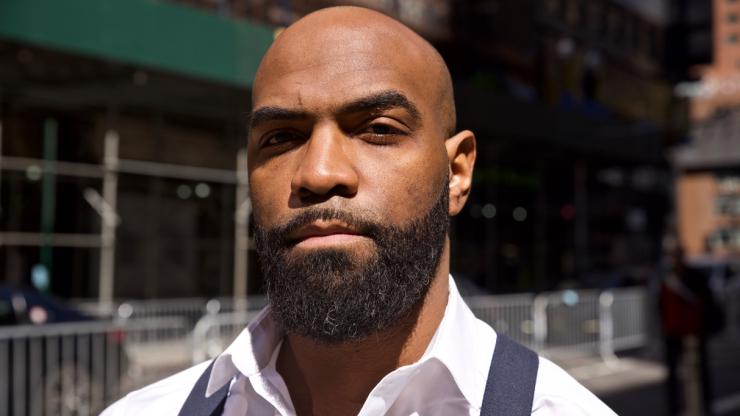

CSHPE alumna Cre Murphy works in and with communities to promote economic opportunities for all

Dr. Lucretia “Cre” Murphy (PhD ’04) has always felt a calling to serve her community, and this is exactly the work she has continued to pursue as a graduate of the Center for the Study of Higher and Postsecondary Education (CSHPE). A senior director at Jobs for the Future (JFF), Murphy works to strengthen the workforce and increase success for individuals and employers. JFF’s driving motivations are equity and meeting employer needs, and preparing for the future workplace. The organization shapes policy that strengthens the labor market at the federal, state, and local levels and drives the conversation for education, workforce, and industry leadership nationwide.

At JFF, Murphy helps develop strategies that increase economic opportunity for individuals and economic prosperity for communities. This work emphasizes integrated approaches that confront structural racism and other forms of bias in policies, practices, and processes. Murphy serves as an expert in education and employment strategies for people who are incarcerated and preparing to reenter their communities. She is a passionate speaker on the economic advancement of young people, adult learners seeking their first credentials, and individuals who have been, or currently are, incarcerated. She also speaks on the importance of confronting race in society, systems, and institutions, so that all people can fully realize prosperity and equal opportunity.

“It is through direct engagement with people ‘on the ground’ and with community stakeholders that I offer an opportunity to talk about structural racism. The way that it comes up in my work is the ways that it is connected to access to education and the job market. Often, people of color in a community have lacked some of both, so my work helps to ensure that they can have access to both,” she says.

More broadly, she asks community members and leaders questions about structures that create or may block opportunity in their community. “For example, when community partners talk about the lack of participation in workforce training programs among Black residents, I ask about the community’s transportation system. Are people physically able to gain access to job training facilities and work sites? This starts to peel back the layers on transportation in neighborhoods that employers are trying to reach. Then, we talk about how their questions of access unveil that it’s not that people aren’t interested in training, but rather it becomes a question of structural inequity and how it operates when it comes to actual infrastructure. If you aren't starting with a conversation about this, then you could be missing out on challenges and also the ability to have solutions,” she adds.

Murphy cites an example of a community in which an employer said that he had many jobs to fill, but that he felt like nobody was willing to work an entry-level job.

In conversation with the workforce system leaders, the employer realized the problem was not about individual willingness.

There was no bus route from many of the community members’ homes to his job site. Two of the work shifts at the site did not align with the bus schedule for those who did have bus service. She uses this example to explain how conversations can unveil the ways in which people can work effectively, and in this case, the employer began to offer a shuttle service. “Focusing on defeat doesn't solve the problem in the end, but understanding the structures of your community does solve the problem.”

Murphy also consults with community members and leaders about barriers for people with an incarceration history and the ways in which structures need to change to make reentry easier. “I have learned a lot of lessons in this work,” she says. “The first one that is reinforced over and over is that people are not ‘the worst thing they have ever done,’ but a criminal status places restrictions on people for life, even if they are 35 and did something at the age of 17. Just as that one moment never defined who that person is, it should not define who they can become. When people have an opportunity to transform their lives, they take it.”

Murphy also learned that, when working with reentry populations, there is great value in investing in transformational experiences and work opportunities for that group. “The payoff is giving better opportunities to these people instead of giving them poor training and poor schooling. The investment pays off in the degree of the transformation for the individual and their families. Since so many of these people become change agents themselves, the investment pays off at the community level.”

Societal inequity is built into the carceral system. “The system targets people by race, and the treatment of women in jail is worse than that toward men. As Bryan Stevenson says, ‘You are more likely to be acquitted if you are rich and guilty than if you are poor and innocent’. This system perfects every inequality we have in the rest of society,” she says. “It’s really disruptive to inequality when people can get a good education because it liberates people from being stuck in this horrible system. This also helps families and communities rewrite their futures. This is really important.”

Many lawyers, policymakers, and community leaders have joined her in the effort to overcome stereotypes that labels people who have been in prison as dangerous, but there is still a lot of work to be done.

Murphy says, “When we debate about how much we want to invest in corrections education, that is not the right question. The question we should ask is how much we want to invest in society, to invest more upfront, to invest in public education and communities. And as for those currently in prison, we need to do more to ensure they can transform their lives and be able to be change agents in their community. I have seen people who have been in prison come out and start businesses where they hire other people who have been in prison. They make things better for people. That’s the truth of investing in people in preparation for when they get out. They can transform their own lives and change their community. They pay it forward when they are invested in.”

In all her engagements with community leaders, Murphy approaches them with humility to see what their assets and goals are, and she seeks a broad perspective on a community, to make sure enough community members have a seat at the table. “We attend their meetings, work with strategic planning, and so on. We also arrange to talk to people independently to have conversations with them based on who they are and where they sit. I found that most community leaders are well versed in how this works and how it impacts their community for better or worse. What they will not be as knowledgeable about is who pulls the levers to make something work. For example, a community may be very engaged in an education issue, but not see the structural racism within it.

I work to bring together all of the people with the right knowledge, the ones with the power, and the ones with the ability to execute change.”

In her work prior to JFF, Murphy ran an organization that worked to educate hundreds of kids who, before attending the Maya Angelou Schools, believed that they were stupid or “bad kids.” At the schools they blossomed as scholars. The organization also expanded their programs to open a school for young adults transitioning from corrections back to the community, and they continue to run a school in the juvenile jail for children who had never had a positive school experience. “Amazing work has continued at these schools,” she says.

The SOE prepared her for this work, says Murphy. “The SOE provided an interdisciplinary structure for research and analysis, and my work today also benefits from being comfortable working across disciplines, systems, and structures. Of course, the research skills I gained are also useful, like understanding and being a critical reviewer of research—and developing qualitative analyses. I have been working with colleagues at JFF who are amazing researchers to create a research agenda for the reentry work we are developing at JFF. I am able to contribute to this work because I studied with faculty and peers at SOE who were brilliant researchers.”

As a student in CSHPE, Murphy was able to work on issues related to the education of Black students. The work she did with other SOE researchers and faculty in public policy, anthropology, psychology, and African American studies informed her dissertation. “It’s given me a framework for analyzing the structures of racism that impact education and work across many domains, but also for understanding the framework for working toward new opportunity structures. Professionally, all of these people would be called part of my ‘network,’ but I am fortunate to continue to call them friends,” she says.

Murphy reflects on society’s growing awareness of social challenges and racism that affect minority groups: “I think we are just at the beginning of making real change internally to be a fully anti-racist organization, so JFF is just the tip of the iceberg of our impact in the field. My hope and plan going forward is to build a platform for changing education and employment opportunities for Black people, and customizing this framework with the particular context for liberation for Latinx, Native American, and other communities. We sometimes talk about education and employment as transactional, but they can also be transformational when we make equity the bottom line. I hope that the work I do will liberate people and communities.”