Meet the Inaugural Alumni Award Recipients

A new annual award is launched in honor of the SOE's centennial

The Office of Development and Alumni Relations has launched two annual alumni awards: the Distinguished Alumni Award and the Emerging Leader Alumni Award. Each award recognizes the incredible accomplishments of alumni, whether they are seasoned professionals or newer to their careers.

In addition to these awards, the selection committee also gave a special honor this year—the Centennial Scholar Award—to a member of the SOE community whose life's work embodies the school's mission and its highest ideals.

Ann Austin

It was while serving as a peer counselor during her undergraduate years at Bates College that Dr. Ann Austin (AM ’82, PhD ’84) came to know Judith Isaacson, then the college’s Dean of Students. A Holocaust survivor who had been interned in a concentration camp as a teenager, Isaacson later immigrated to America and studied at Bates herself. Austin recalls her vividly as someone who was “filled with life and joy” as well as a desire to “support the learning of students and their life development.” Her influence left a lasting impression on Austin. “I thought, if I could have the kind of positive influence that she had in terms of the compassion, the way in which she supported the learning of the undergraduates—that would be a career well worth living. She is the inspiration that made me think I’d like to go into higher education.”

Following a master’s program in higher education at Syracuse University, Austin gained administrative experience as an admissions counselor. By the time she got to U-M as a doctoral student in the Center for the Study of Higher Education at the SOE, she had become interested in academic work itself, and, while in graduate school, specifically the academic workplace.

“Studying the academic workplace leads you to think about questions around teaching and learning, as well as the overall purpose of the university, and how we translate our work into application and practice,” says Austin.

As she continued to study both topics—the academic career and improving teaching and learning—she began to realize the issues she was drawn to all had to do with change within academic contexts. Ultimately, Austin homed in on the training of doctoral students.

“They’re very well prepared for research, but not always as much for teaching,” says Austin. “How do we improve their preparation so they can teach better?” It was a matter, she recognized, of organizational change. She focused much research on the professional development and learning of faculty members, and her research caught the attention of the National Academy of Sciences who recognized the struggle for researchers to integrate what research tells us about effective teaching and learning into their own practice. “They literally called me up one day and said, ‘Could you write a short paper and explain why we know a lot about good teaching but it is hard to get faculty to change and use what we know?’” They imagined the problem would be fairly easy to address, recalls Austin with a laugh. The paper she produced articulated why it is hard to change how faculty do their work—and it struck a chord. After publication of the paper, people from across the STEM fields began to contact Austin, eager to understand more about how change happens in academe, especially to improve teaching.

In 2003, Austin co-founded the Center for the Integration of Research, Teaching, and Learning (CIRTL), a network of prominent universities dedicated to helping science graduate students develop teaching skills they can use to enhance learning in the sciences, especially at the undergraduate level. The original collaboration among six universities has expanded to more than 40 today.

The paper she produced articulated why it is hard to change how faculty do their work—and it struck a chord. After publication of the paper, people from across the STEM fields began to contact Austin, eager to understand more about how change happens in academe, especially to improve teaching.

“CIRTL was not only a practical action project dedicated to strengthening teaching in the sciences,” wrote a colleague who nominated Austin for the Distinguished Alumni Award, “it was also a research project that yielded grants and publications.” A National Science Foundation grant was among these, which Austin received to study the use of networks as a means to scale improvements in undergraduate STEM education. Another project involves changing the evaluation of teaching to promote more faculty reflection, collaboration, and improvement. In the two decades since then, her work around organizational change has evolved to focus as well on inclusivity when it comes to race and gender, particularly in STEM fields.

An internationally renowned scholar, Austin has traveled the world sharing her research and expertise with university administrators and faculty leaders. In 1998, she was recognized by Change Magazine as one of 40 “Young Leaders of the Academy.” In 2000, she was elected President of the Association for the Study of Higher Education. She is the author or co-author of 50 book chapters and dozens of articles in peer-reviewed journals and practitioner-focused venues where she has translated research to practice. She has received ASHE’s Research Achievement Award, the Exemplary Research Award from Division J in AREA, and a Fulbright Fellowship in South Africa. Numerous nominators cited Austin’s excellence as a scholar, teacher, mentor, and administrator, as well as her national and international reputation—a “quintuple threat,” as one nominator put it.

Currently University Distinguished Professor and Interim Dean of the College of Education at Michigan State University, Austin says it is important to her to be motivated by a set of values that demonstrate kindness and compassion. “I try to live a life that is going to help make other people’s lives better, make the world better.”

As a young faculty member raising three children, Austin says she realized the importance of exercising gratitude. Rather than think of what she had to do for her kids or her job as obligations, “I thought it would be better for me to say to myself, I’m incredibly fortunate to have a life that’s filled with wonderful things—wonderful work, wonderful people I love. When things get hard, I remind myself that I have a lot to be grateful for.”

Brian Burt

Not yet a decade out of his doctoral program in the SOE’s Center for the Study of Higher and Postsecondary Education, Dr. Brian Burt (PhD ’14) already has an impressive record of publication—including 16 articles in top-tier journals, four book chapters, and two research briefs. But what stood out to the former student who recommended Burt for the Emerging Leader Alumni Award wasn’t the sheer volume of his work. “Nine out of the 16 articles [Burt] has published since 2014 were co-authored by graduate students,” noted the recommender, highlighting the young professor’s commitment to helping his students navigate all aspects of academia—including publishing. He went on to write that Burt’s mentorship extended in numerous other directions “from quick text conversations about decisions, to helping me conceptualize research ideas, and reminding me that I was indeed worthy of being at Michigan.”

Burt’s research explores the experiences of underrepresented graduate students of color in the field of engineering, a topic he came to while a doctoral student at U-M. As a new student adapting to the rigorous academic environment, Burt kept his social life to a minimum. But when friends in the College of Engineering invited him to join their circle, Burt picked up on something.

“I didn’t really hang out that much, but some of my friends were in STEM programs across campus, and they had lots of gatherings. I was always curious why they were gathering so often. I began to wonder if they knew that by gathering, they were retaining each other.”

What started as simple intellectual curiosity soon turned into a project for the qualitative research class Burt was taking at the time with Dr. Michael Bastedo.

“I didn’t have to have an end goal in mind to start the project,” recalls Burt. Bastedo encouraged him to see where his curiosity led him. “I knew there was something that I was observing, but I had no clue what it was. That’s what made me excited. I was trying to figure out the details of something that wasn’t clear in the knowledge base at all.”

Prior to the qualitative research class, Burt had envisioned a career in higher education administration—perhaps as a dean, or a vice president of student affairs. But pursuing the mystery of the unexplained phenomenon he was witnessing among his friends in STEM made him feel like a detective. He was hooked.

“It was the first time I remember saying out loud, ‘I feel like a scholar.’”

Now an associate professor of Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis at the University of Wisconsin, Burt says that every aspect of what he does on a daily basis is related to equity, diversity, and inclusion.

“My research deals with broadening participation among Black men and other underrepresented populations in STEM. It’s about helping to address and redress systemic and historical issues that have prevented people from having access to these fields. And realizing that to solve the nation’s and the world’s biggest problems, we have to figure out ways to get more people in these positions to help contribute and solve these issues.”

Although Burt’s scholarship focuses on the STEM fields, his research translates to his own professional practice as a mentor. Well aware that imposter syndrome can set in, Burt has students complete a self-evaluation at the start of each semester. He also asks for an updated CV. His aim is to help his students create a record for themselves so that they can sense their own progress without relying on his recognition—or that provided by awards and publication—to feel a sense of their own achievement.

“I want them to feel excited about their growth and their own learning, not necessarily the external reward.”

Reflecting on his time at the SOE, Burt says that he benefited from mentors including professors Lisa Lattuca, Carla O’Conor, and Philip Bowman. He also recalls a standing weekly lunch date he had with two fellow CSHPE students (Drs. Christopher Nellum and James Ellis). Together they celebrated each other’s victories of the week, and discussed challenges they might have had.

“They allowed me to dream about what I would be like if I were to become a faculty member. I remember saying that I would never want any of my students to ever question that they were good enough or why they were there, or that there had been a mistake about them being in the program.”

Burt says that the mentorship he benefited from served as the model for what practices today. So whether it’s co-authoring an article, or connecting them with contacts in his network, Burt brings his students along with him.

“Everything that I’m doing—at every stage—I’m including my students in these processes.”

Travon Jefferson

Travon Jefferson (ABEd ’16) still recalls the advice Dr. Kendra L. Hearn bestowed on him when he was an undergrad at the SOE.

“I remember sitting in her office and she was explaining to me that one powerful thing you can always have your students do is write. Have them write every day.”

In his fifth grade classroom in Houston, Texas, Jefferson put Hearn’s advice into action by having his students keep journals. Jefferson provided prompts like, “If you had a superpower, what would it be?” or “If you could go back in time and change one thing, what would you do?”

“Originally, a lot of the topics were lighthearted. But when I actually read the journals, I noticed they were pretty dark.”

One student wrote, “I wish I had the power to control the weather. That way, when Hurricane Harvey happened, I could have stopped it.” The student went on to explain that their family was displaced because of the storm, and had to stay in a shelter. Another student wrote of wishing she could go back in time and stop her father from committing suicide.

“I realized, I’m coming in here and teaching these students every day, and this is the baggage they’re carrying. When do they have the opportunity to deal with it?”

Following graduate school, Jefferson was selected to join Teach Plus Texas as a policy fellow, a rigorous professional development program for teachers who want to become leaders in shaping education policy and advocacy. The cohort was asked to identify problems facing their school communities. Some fellows brought up instruction, others mentioned school finances. But between Hurricane Harvey, the racist 2019 massacre in an El Paso supermarket, and the regular occurrence of school shootings, when it was Jefferson’s turn to speak, he said his students’ mental health was under attack.

“We can’t just rely on the school counselor,” says Jefferson, noting that his school at the time had one counselor for 500 students. “Counselors are great, but they’re spread thin. So the teachers are the first responders.” Jefferson’s Teach Plus fellowship cohort comprised teachers from across the state. As he spoke to the group, he noticed that his colleagues were all nodding in agreement. “No matter if they taught in a rural, urban, suburban, private, charter, or public school—every teacher agreed that our students need mental health support.”

A working group was formed to write a policy recommendation which would require Texas school districts to train staff in trauma-informed care and include trauma-informed instruction training among the components of renewing a teaching certification. Jefferson wrote an op-ed titled “Train Teachers to Support Students Who Have Experienced Trauma.” It picked up steam on Twitter—it was retweeted by John B. King, Jr., former Secretary of Education in the Obama administration and founder of My Brother’s Keeper, among many others. The superintendent of Houston’s independent school district wrote Jefferson personally to congratulate him on the piece.

With his working group’s policy memo in hand, Jefferson went to the state capital to meet with legislators.

“They were like ‘Wow, this type of problem doesn’t have a political side. Whether Republican or Democrat, or in between—everyone needs some type of mental health support.’”

Eventually, the exact language his group had proposed in their policy recommendation was incorporated into Texas House Bill 18, which increases mental health training for educators and other school professionals to aid in early identification and intervention, emphasizes the importance of mental health education for students, and improves access to mental and behavior health services through school-based mental health centers and the hiring of mental health professionals. The law went into effect on September 1, 2021.

Jefferson, who is now a lead fellow with Teach Plus, has shifted his focus to teacher retention. He has developed the Liberation Coalition, an affinity group for educators of color who are promoting anti-racism in their classrooms and school policies. A colleague who nominated Jefferson for the Emerging Leader Alumni Award noted, “Travon is a leader in the school community here. He is the reason I became a teacher in Houston.”

Currently a seventh grade social studies teacher at KIPP Spirit College Prep, Jefferson prides himself on teaching culturally relevant texts. He still has his students write in class, and he practices what he preaches: outside of school, he’s at work on a novel.

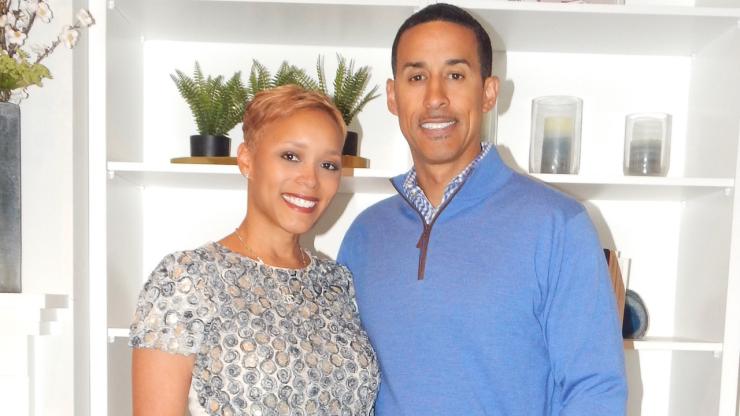

Alycia Meriweather

As a child, Alycia Meriweather (ABEd ’95, TeachCert ’95) loved playing school. She gathered her stuffed animals together, sometimes throwing her two little sisters into the “class” as well, and proceeded to lead the day’s lesson.

“As I’ve gotten older, I understand that it’s somewhat rare to know exactly what you want to do at an early age. I always knew I wanted to be a teacher, and I always knew I wanted to come back to help with the revitalization of Detroit through public education,” says Meriweather, a lifelong Detroiter who is now the Deputy Superintendent of Partnerships and Innovation for the Detroit Public Schools Community District (DPSCD).

She got her start in room 128 at Farwell Middle School on the east side of the city. There, she channeled her passion for science to inspire her seventh grade students. It was also where she first met Dr. Elizabeth Moje, who was then part of a team of U-M researchers piloting the LeTUS curriculum, an effort to foster inquiry-oriented science instruction in urban middle schools.

“Being part of that project really helped accelerate my career, as both a teacher and a leader,” recalls Meriweather. The work she launched in partnership with several SOE projects spread across the school district. She began to write curriculum and lead professional development workshops. When a colleague whose work she admired passed away, she applied to fill their role, making the leap from the classroom to administration.

“To leave the classroom was a very difficult decision for me because I love kids so much. But I also knew from the professional development sessions I’d been facilitating the impact I could have on other teachers and their students. At the middle school level, a teacher is teaching potentially 150-180 students every day, so if you can impact the teacher, you can exponentially impact the number of students who are having a better learning experience in Detroit public schools, and that really interested me.”

She became the city-wide supervisor of middle school science, eventually heading the science department for the district, and then heading the curriculum department, where she oversaw mathematics, science, social studies, ELA, athletics, world languages, music, and art. From there she went on to serve as interim superintendent for 14 months as the district transitioned from state to local control.

Meriweather’s efforts to impact change extend beyond her district. She takes seriously her role in helping legislators and other decision makers understand the impact their policies will have when put into practice. “Oftentimes, people who are making policy don’t have a connection to the implementation of the policy. You have to help people who don’t do this work every day understand the importance of the work, the impact of the work, and what their decisions mean.”

On behalf of DPSCD, Meriweather’s work in partnership with the SOE has continued over the years. Now a member of the Dean’s Advisory Council, she has been instrumental in guiding the P-20 partnership and development of The School at Marygrove.

Meriweather still misses teaching in the classroom, but as a driver of change, she keeps her ears open, taking every chance she gets to hear from her best informants: kids. On a Saturday last fall, overseeing a vaccine clinic that was taking place in a district school, she spoke with students as they waited in the observation area after receiving their shots. She pulled up a chair next to three sisters and began to chat. Where did they go to school? Did they like it? Who was their favorite teacher? Which class did they enjoy the most?

The same reasons she loved playing school as a kid herself still hold true.

“Every single title I have held during my career in DPSCD has been a blessing, giving me the privilege and opportunity to make decisions, influence policy, and implement programs to make life better for kids in Detroit—my childhood dream has been my lived reality and I am truly thankful!”

Laura Perna

Having grown up in a small town in northern New Jersey, moving to the city of Philadelphia to attend the University of Pennsylvania was “a big deal” for Dr. Laura Perna (MPP ’92, PhD ’97). Initially she thought she wanted to become a medical doctor, but the more social sciences courses she took, the more interested she became in issues around stratification, and the many ways in which inequality manifests itself. She got to know patients and became familiar with the challenges they faced while volunteering at a nursing home and in a psychiatric hospital, but soon realized she didn’t want to provide direct services. “I wanted to create structural change,” recalls Perna, who saw that the opportunity to go to a school like Penn, get a good job, or have a house to live in, shouldn’t be reserved for a lucky few. “Everyone should have those things. For me, public policy has been the way to figure out how to level the playing field and address structural inequality.”

After college, Perna took a job working for a county government in New Jersey where she saw the impact of local agencies on the lives of residents. While there, she was also introduced to people who worked at a number of local colleges. But it wasn’t until a few years later, as a graduate student at the Ford School of Public Policy, that she realized the power of those initial introductions: every paper she wrote ended up circling back to education.

“Figuring out how to pay for college was an issue that was especially relevant to me and my family,” says Perna, who began to explore the topic more deeply. By the time she enrolled in the CSHPE doctoral program at SOE, financial aid had become one of her main areas of interest.

Today Perna is the Graduate School of Education Centennial Presidential Professor of Education, Executive Director for the Alliance for Higher Education and Democracy, and Vice Provost for Faculty at her alma mater, the University of Pennsylvania. Perna is one of the few faculty members who has led both of the major scholarly associations affiliated with the study of higher education by serving as the president of ASHE (Association for the Study of Higher Education) and the vice president of AERA (American Education Research Association) Division J, Postsecondary Education. An internationally renowned scholar, her work has changed scholarship and practice to improve college access for low-income students, first-generation students, and students of color.

But in keeping with her mission to create structural change, Perna’s influence extends far beyond the halls of academia.

“I really believe that policy and practice should be informed by data and research, but policymakers are not reading our academic journals,” says Perna. “I think it’s an obligation, especially for people who choose to be in our applied field, to help make that connection.” She has given testimony to the U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, and the Subcommittee on Higher Education and Workforce Training for the U.S. House of Representatives. As an expert she has advocated for federal and state policy to provide access to higher education for student populations that have been excluded. In addition to publishing in academic journals, her expertise is often quoted in popular media outlets, from the New York Times to Forbes, and many more.

Understanding the immense value of community partnerships, Perna created an academic-based service-learning course where Penn graduate students can apply college choice and access theory to work in the nonprofit sector of Philadelphia to encourage access to high school students. “Dr. Perna’s connection to practice and policy puts her among the rarest of academics who can engage with communities and make meaningful change in policy, all while producing rigorous and seminal scholarship,” writes a mentee who nominated her for the Distinguished Alumni Award. The nominator, who wasn’t even enrolled at Perna’s institution but came to know her through conferences and professional networks, wrote in awe of Perna’s willingness to help guide him.

“When I was at Michigan in the doctoral program, I was so grateful for the time, care, and attention—the engagement of the faculty there,” recalls Perna. “Joan Stark was on my dissertation committee. At some point when I was close to being done, I remember saying to her ‘What on earth can I do to thank you? You’ve been so helpful.’ And she said, simply, ‘You pay it forward. This is just part of being in this profession.’ It was an explicit way to communicate norms and expectations, and it certainly has stuck with me. Mentoring is so personally gratifying. It’s such a privilege to be part of other people’s journeys.”

Lin Chu Wong

Dr. Lin Chu Wong (AM ’80, PhD ’90) had just sent her eldest child off to college when she returned to school herself. Although she had graduated from Hunter College in 1950, she hadn’t worked in 20 years when she enrolled at the SOE to earn her master’s degree. At age 40, she was older than both her classmates and her advisor, Dr. Gwendolyn Baker, but that didn’t deter her.

As a child growing up during the Depression in New York City, Wong had worked after school in her family’s Chinese laundry. “I was aware of being the only ‘Chinese girl’ in my elementary school and that, unlike the other girls, I lived behind a laundry store,” recalls Wong. “I felt that I had to overcome both economic and ethnic obstacles. When I recounted taunting, mimicking, and bullying, and as wartime animus against Asians was unleashed, my mother, who had only two years of high school education, and my father who was English-illiterate, made it clear to me, as well as to my siblings, that I needed to go further.”

Wong became the first in her family to complete college. She married James Wong after his U.S. Navy discharge and helped support him while he pursued his university degree. They raised four children in Ann Arbor.

Armed with her new teaching certification, Wong began substitute teaching at schools in her neighborhood, then known as East Ann Arbor. When Clinton Elementary School expanded to incorporate students from the burgeoning subsidized housing units in the area, its enrollment leapt from 100 students to 600. Wong interviewed for a full-time position on a Friday, and began teaching her second grade class the following Monday. The school was so crowded, she didn’t even have a classroom; she taught in a hallway, or sometimes, in a storage room. But she was determined to give her students powerful learning opportunities.

“I found my first teaching experience exciting and empowering,” recalls Wong. “The students and I were inventing new ways to do school. We shared a spirit of overcoming unfortunate odds, and turned school into an adventure.”

The severe overcrowding led the Ann Arbor School District to open a new school in a rented warehouse, closer to the subsidized housing units. A sign-up sheet for volunteers to transfer went up in the faculty lounge at Clinton. Wong remembers that she was one of the few to add her name.

“Clinton was originally intended to serve families from a middle class, predominantly white community,” she says. But the new school, which would eventually be named Bryant Elementary, would become Ann Arbor’s first open school, and would serve a more diverse, and largely Black, community.

“My own experience as the only student of color in most of my New York City classrooms from elementary through college, inspired me to sign up,” Wong says. The colleagues who joined her shared a similar philosophy. “We all believed that the foundation of educational success was in a progressive elementary school education with a diverse staff and student body.”

Wong taught at Bryant for 20 years. Eventually, moved by the “heady days of the feminist movement,” as she puts it, she wanted to take a stab at being in charge. She became principal of Bader Elementary School, which she was tasked with closing over a two-year period and transitioning the student body to a more integrated school via busing.

While teaching full time, Wong earned her PhD. Her dissertation, titled “An Ethnographic Study of Literacy Behaviors in Chinese Families in an Urban School Community,” examined recent Chinese immigrant students in Detroit, and considered the clash between their traditional valuation of education and the reality of their school experiences. The dissertation focused on how the students’ non-English-speaking parents invented teaching strategies and motivated them, and how a more supportive public school system could affect success in an overlooked minority community.

Born out of her personal experience of racism, Wong’s interest in multicultural studies led her to curriculum development. In 1985 she was selected to serve on the National Education Association’s Curriculum Committee in Washington, DC, where she helped to write a national multicultural curriculum. In 1991, Wong was reunited with her former SOE advisor Gwendolyn Baker, who was now the president of the New York City Board of Education. She invited Wong to contribute her ideas on multicultural teaching at the elementary level in her hometown.

“She knew about my past in a variety of New York City schools,” says Wong of Baker. “Both of us had experienced segregation and bias, and we exchanged anecdotes of those not-so-far-off, yet still present, times. We agreed that children, in order to invent their own lives, should be motivated in school to examine their heritage and the culture of others. What was unimaginable to a student like me in 1930s New York City was a curriculum telling the story of the many cultures that constitute the richness of the American experience.” Along with Baker, she was able to help formulate just that for a new generation.

Subsequently, Wong was elected to serve three three-year terms on the SOE Alumni Board of Governors. Over the course of her tenure, she worked on issues that included recruitment and retention of minority students and building relationships with Detroit public schools.

“The racism of my youth and the advent of civil rights in the 1960s all added up to the person I became,” says Wong in reflection, “someone inspired to develop studies in diversity and to teach culture and tolerance.”