Growing Economic Opportunity Through Community Colleges

Professor Peter Bahr’s research aims to improve the way community colleges serve the diverse needs of students

Community colleges open doors to economic opportunity and advancement for many students who would otherwise be unable to attend college. But these institutions comprise an educational ecosystem that can be much more complex than the one typically found at four-year universities. With more than two decades of experience in research on community colleges, Associate Professor Peter Riley Bahr is engaged in several high-profile studies exploring how students are using these colleges and other open-access postsecondary institutions, and how the institutions and state agencies that oversee them can better serve learners by adapting to their demonstrated needs.

Bahr's research on community colleges stems in part from his personal experience as a community college student. Bahr attended Solano Community College in Fairfield, California, while working nights at a wastewater treatment plant. He completed associate degrees in chemistry and in water and wastewater treatment technology, but had little guidance regarding what to do next. Ultimately, he found his way to California State University Sacramento as a transfer student, and then was accepted into a PhD program in sociology at the University of California Davis. He ascribes his decision to seek a PhD to a misunderstanding on his part, when he didn’t recognize as a joke a professor’s statement that “everyone should get a PhD.” But this advice proved providential, as it put him on a path to a research role with the state agency overseeing community colleges in California, and from there to faculty positions first at Wayne State University in Detroit, and then in the Center for the Study of Higher and Postsecondary Education (CSHPE) at the University of Michigan.

"Now I'm seeing that it's not just my own experience, but that of millions of students navigating their way through the curriculum, encountering obstacles, often unclear about the best path forward," Bahr says. Describing himself as perpetually curious about the answers to the question "why do people do what they do?", Bahr notes that community colleges attract people from incredibly different backgrounds with a wide range of goals; they also often offer a less structured environment than four-year colleges, leading to substantial variability in student pathways into, through, and out of the institutions. By deciphering the relationships between students’ motivations, behaviors, and outcomes, his research informs institutional and state policy decisions about how to improve students' educational and economic opportunities.

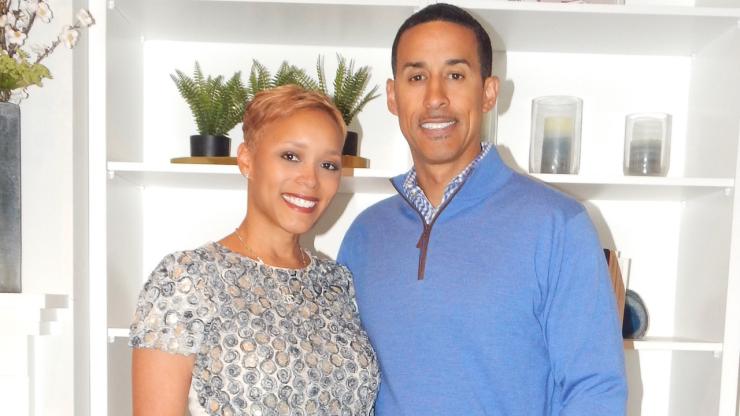

Bahr's work is supported by a research team that shares his vision. Dr. Kennan Cepa, Managing Researcher on Bahr’s team, has responsibility for project planning and grant proposals in addition to conducting research. Jennifer May-Trifiletti, Dr. Xinye Hu, and Rooney Columbus each oversee one or more specific research projects. Sam Kaser, who received his master’s degree from CSHPE and is currently a doctoral student at the University of Iowa, provides research support.

Cepa says that her experience graduating in the midst of the Great Recession deeply informed her perspective on the difficulties of bridging school and work. "Community colleges are such an important linchpin for Americans to get a stable foothold in the precarious economic circumstances that define American life today," she says.

Skills Builders

Bahr's recent research with doctoral student collaborators Yiran Chen and Rooney Columbus on "skills builder students" was recently accepted for publication in the Journal of Higher Education. "Roughly one in eight students in community colleges are taking just a couple of classes, mostly in career and technical education fields, and having very high levels of success. But they typically leave college without earning a degree or postsecondary certificate," Bahr says. Even without a formal credential, though, the students frequently see improvements in their earnings that can be attributed to their studies.

"It's remarkable in some ways, because our narrative is that people who leave college without completing a degree have dropped out. But of course, in community colleges, it's so much more complex," Bahr says.

Bahr likens students carving their own paths through the community college system with "desire lines" carved through the careful landscaping of Central Park in New York. The design of the park suggests a particular use, but the people interacting with the space forge their own paths.

"Students’ emergent course-taking patterns present the opportunity for the institution to be informed by what users need and are benefiting from," Bahr says. "Students are able to convert these one or two courses into significant economic returns. The curriculum of the institution can be modified, expanded, developed, refined to serve those needs more

directly." He suggests that colleges could build credential programs based on the combinations of high-return courses that students are taking.

"Think about it like you're going to the grocery store," Bahr says. "You've just got a little basket, you bought turkey and you bought cheese and you leave. That's all you wanted. You didn't know anything about bread or mustard. If you had realized that you could make a sandwich just by throwing a couple more groceries into your cart, then you would get an additional benefit from your purchase." Bahr sees an opportunity, then, for institutions to offer a credential as a "full sandwich" by making it easy for skills builder students to access each ingredient in the same educational "aisle," with benefits for both the learner in labor market outcomes, and benefits for the college in the tangible measure of graduation rate.

"So now the skills builder student leaves with a certificate that is durable, that goes beyond their immediate educational and economic needs, something that can take them even further, that's portable, that goes from one college to another."

Community Colleges and Career Technical Centers

In examining the community college system, Bahr is also interested in lessons from other sub-baccalaureate programs, especially the state of Ohio's successful career and technical centers (CTCs). CTCs appear to have better graduation and employment rates than community colleges. Bahr and his team, in collaboration with colleagues at Miami University and Xavier University, set out to discover whether the apparent advantages of CTCs over comparable community colleges hold up under scrutiny and, if so, how the community college model of career and technical education might be adapted to better serve students.

"Our preliminary evidence suggests that the differences in outcomes between career and technical centers and community colleges are not solely a result of differences in the student body. Moreover, the credentials offered by career and technical centers appear to be worth at least as much as comparable certificates from community colleges in terms of earnings gains," Bahr says. "That's pretty exciting because it says there is another model for delivering education in these career and technical centers that we can learn from, and that doesn’t come at the cost of the value of the credentials.

"What we're finding is fascinating," he continues. "For the longest time, we thought the best way to make community college work well was to make it maximally flexible. You make it as flexible as possible, especially for adult learners who are juggling kids, jobs, and so on." Ohio's technical centers, though, do the opposite. A student hoping to earn a certificate from a community college may know the classes they need to take, but those classes may be stretched out over multiple semesters or scheduled at times that don’t fit the lives of adult learners balancing work, family care, and the like. But students in a career and technical center enter as part of a cohort and complete their coursework in a predictable, structured time frame, for a set cost. "That seems to actually serve some segments of the adult learner population better because it takes all of the question marks out of it. The predictability makes it possible for students to restructure their lives for a short time to achieve their educational goals." Bahr also noted that instructors at CTCs are often working in or recently retired from the occupation they're teaching, and that proximity to the industry means they know what students need to learn to be successful in their jobs.

Stackable Credentials

Bahr and his team, in partnership with Lindsay Daugherty and Peter Nguyen at RAND, are also studying stackable credentials as a path toward economic opportunity. "For a significant fraction of students, it's not feasible to just go full time at a university," Bahr says. The goal is to create paths that build from a lower-level credential with a meaningful economic benefit up to higher levels with greater economic returns.

"That sort of a stacking gives students the on-ramps and off-ramps that they need to get immediate economic gains, secure their employment, continue in school and achieve their goals," Bahr says. "That's the interest in stackability, creating ladders of credentials that allow people to advance their economic opportunities progressively, as opposed to waiting four or five years to complete a degree to secure the economic benefits of their education."

“We've identified stackable credentials pathways as a promising way to help low-income students move into a middle income wage and life,” says Jennifer May-Trifiletti, the Research Lead for the stackable credentials project. “The focus of our project is explicitly on promoting equity by identifying the barriers that hinder access to stackable credential pathways for low-income students, specifically barriers that institutions and state policymakers have some control over so that they can make these pathways more accessible and beneficial for low-income students.”

Building Systems that Serve Students

Bahr and his research team rely on strong partnerships with the states and institutions they are studying. "We aim to leverage the data that states share with us to answer the questions that will help our partners understand what's happening in their systems and determine how to better support their students, in addition to advancing knowledge for the larger community of researchers and scholars," Cepa says.

Because community colleges are more likely than four-year colleges to serve economically marginalized students, students of color, and adults returning to further their education, Bahr and his colleagues take seriously their role and responsibility in improving access to higher education.

"You can see that central to our work really is serving students who have limited or minimal economic opportunities," Bahr says. "Higher education opens doors to advance beyond whatever your socioeconomic background might be or whatever your parents may have achieved. You can go further. You can climb higher. That's the promise of America."