Teaching with Art for Equity

UMMA and the SOE work together to tackle art education’s unsettling history

As has long been the case, arts instruction is far from a given in America’s many under-resourced public schools—although it’s not clear how bad the problem actually is, since the last comprehensive national arts education report by the U.S. Department of Education is over 10 years old. In Detroit, for example, roughly half of schools offer no formal instruction in music or art.

Far from the exception, under-resourced schools are now the norm in the United States. According to a 2020 study by The Century Foundation, a majority of school districts in the country—7,224 in total, making up almost two-thirds of all public-school students—face a “funding gap” (the amount of school funding needed to bring students up to the nation’s current average outcomes). Unsurprisingly, districts with funding gaps serve a disproportionate number of low-income, Black, and Latinx students.

The issues surrounding arts access and representation that proliferate in under-resourced schools are similarly reflected in the arts community itself. Children who are not exposed to the arts and artmaking in school are far less likely to grow up to be artists, continuing a cycle of exclusion and underrepresentation of artists of color while privileging artists from more affluent communities whose work is more likely to end up in galleries and museums.

In an effort to tackle these issues around access, equity, and representation, the University of Michigan Museum of Art (UMMA) and the SOE are developing a unique partnership that focuses on learning through and with art, and applying the art of teaching to the teaching of art.

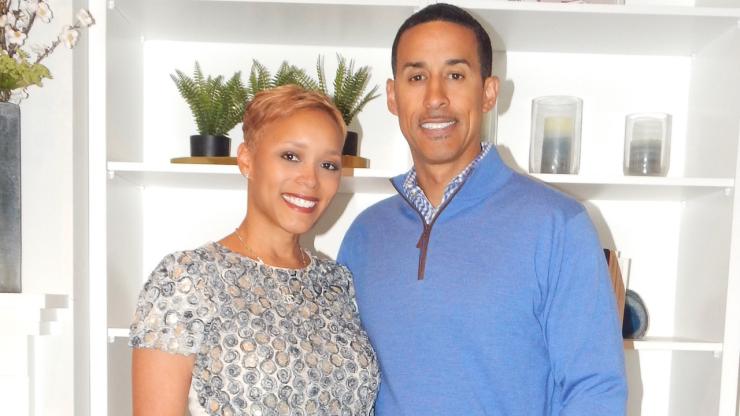

Jim Leija, UMMA’s Deputy Director for Public Experience and Learning, explains that “this sustained, intentional collaboration between UMMA and the School of Education harnesses our collective resources towards research and practice on how learning through visual arts can advance equity in a variety of educational settings. We’re interested in how experiences with visual art can speak to students’ identities, create community and social bonds, help them explore complex social issues, and be a site for multimodal learning that doesn’t typically happen in the classroom.”

The partnership was established, in part, to grapple with how to speak and teach about UMMA’s current Unsettling Histories exhibit. The exhibit itself was organized as a response to the Museum’s recent acquisition of Titus Kaphar’s Flay (James Madison). Kaphar, a Michigan native who holds an MFA from the Yale School of Art, is an established artist whose work can be seen in museums and galleries throughout the country. His piece, Analogous Colors, was featured on the cover of the June 15, 2020 issue of TIME. In an artist statement, Kaphar explains that his “practice seeks to dislodge history from its status as the ‘past’ in order to unearth its contemporary relevance.”

In Unsettling Histories, students and educators encounter UMMA’s collection of European and American art from the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries through the lens of slavery and colonization. The artworks in this exhibition were made almost exclusively by white, male artists who lived in a world shaped by the ideologies of colonial expansion and Western domination. Kaphar’s work is the catalyst for the examination of the unsettling histories that are contained in UMMA’s collection (and in museum collections more broadly) and analyzes why some stories and histories are prioritized over others.

Leija continues: “Our collaboration is determined to dismantle the barriers that marginalize BIPOC folks in museums and build a true sense of belonging and community for those who have been implicitly and explicitly excluded.”

Grace VanderVliet, UMMA’s Curator for Museum Teaching and Learning, adds that the partnership also hopes to “leverage works of art from UMMA's collection in order to develop teaching approaches that are just, equitable, and inclusive."

The collaboration has already begun to work on several projects and imagines a wide array of possibilities where the partnership can have an impact—from the training of museum docents to a reimagined curriculum for preservice educators.

Victoria Shaw, Detroit Schools Partnership Lead, noted that “a key principle of this growing partnership is to center Detroit-based expertise, leadership, and epistemologies while surfacing often-invisible barriers—for example transportation, childcare, scheduling—to genuine collaboration between university and community partners.”

UMMA and SOE hosted their first joint event in fall 2021—a teacher summit in which local educators convened and offered input on how they might use objects in UMMA's collection as a springboard for their classes and curricula. “Our hope was that this group would act as a catalyst and start the discussion,” VanderVliet says, “bearing in mind that we didn’t want to predetermine what role they would have before they weighed in.”

The summit, funded by a grant from U-M’s National Center for Institutional Diversity, included participants from the Detroit nonprofit InsideOut Literary Arts; representatives from five public schools in Detroit, Ypsilanti, and Ann Arbor; and staff and faculty from UMMA, SOE, and University Musical Society.

VanderVliet says, “the summit helped UMMA consider exhibitions and objects in light of curricular connections, how gallery teaching pedagogy relates to classroom practices, and how teaching with art can move us toward equitable approaches in thinking about and framing history and literacy.”

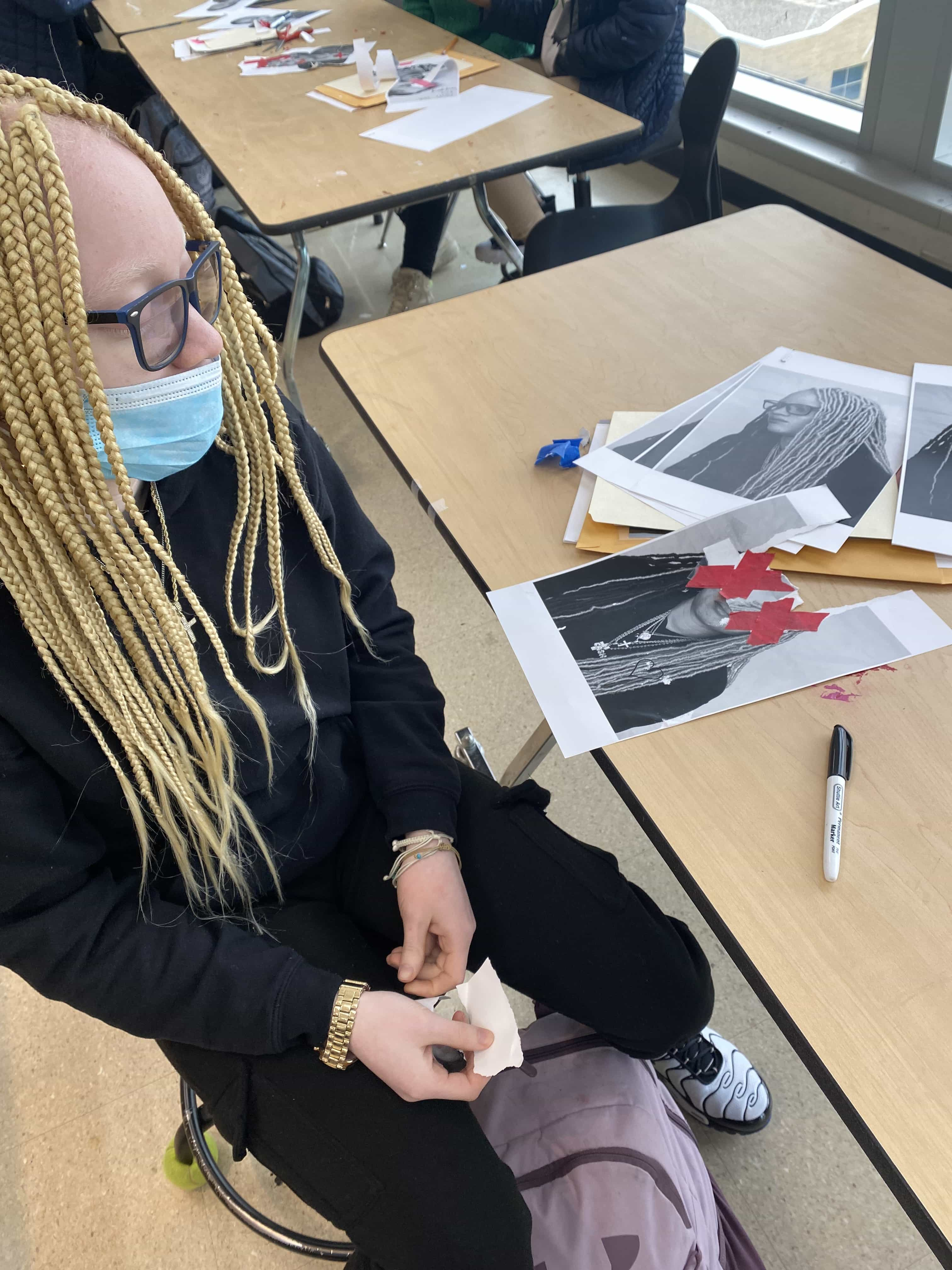

Following the teacher summit, VanderVliet and Cheyenne Fletcher, UMMA’s K-12 Education Coordinator, visited Ms. Kim Hildebrandt-Hall's Figure Drawing Class at the Detroit School of Arts (DSA)—a fine and performing arts high school that offers a strong college preparatory academic and arts curriculum. The visit was in preparation for her students’ field trip to view the Unsettling Histories exhibit. VanderVliet and Fletcher discussed with students how art can encourage conversations about self-representation, tough-but-real history, and land relationships.

In addition, Yvette Rock, an artist-in-residence at DSA who holds an MFA from U-M and is the founder of Live Coal Gallery in Detroit, worked over several weeks with Hildebrandt-Hall’s students to study other pieces by Kaphar, touching on themes, media, techniques, and social justice concerns.

Rock explains that she “wanted this project to demonstrate that creating access points to art, artists, art-making processes, art spaces, and the sharing and ownership of art can create a healthy and vibrant art ecosystem for those whose personhood and art would normally be ignored, disregarded, and undervalued.”

Students created several projects of their own using similar techniques to Kaphar to explore and express their own concerns, commitments, and identities. Rock took a series of photo portraits of the students, which they used in various ways—including cutting, crumpling, erasing, shredding, and using other mark-making approaches—along with printed landscape images from UMMA’s collection, to create layered pieces that challenged students to embed themselves in existing spaces or radically alter their visual environment.

“I want to empower Detroit youth with tools and resources that will impact their lives today and tomorrow,” Rock says.

In addition to direct work with students, the partnership’s plans include helping beginning teachers learn how to combat systemic racism and structural inequality by using visual art in their teaching. Art can open discussion to personal connections and experiences. For example, preservice kindergarten teachers planned a unit in which they asked students to draw a house before and after looking at images of buildings designed by architect Zaha Hadid. Expanding perspectives on "the norm" and challenging who creates those expectations feels natural when discussing visual art. To this end, UMMA and the SOE will collaborate to redesign a key unit in a course for elementary teacher candidates to focus on teaching for equity with visual art.

Funded by a grant from U-M’s Center for Research on Learning and Teaching, this elementary teacher education course sequence, Teaching with Art for Equity, will focus on the arts as a rigorous form of expression and communication. By focusing on BIPOC artists and the potential visual arts have to generate knowledge while making ideas and feelings visible in non-verbal ways, Katie Robertson, SOE Lecturer in Teacher Education and one of the key developers of the course, hopes this will lead to deeper sociocultural understanding.

“We will work with teacher candidates and in-service teachers to explore the ethical necessity of focusing on dije (diversity, inclusion, justice, and equity) priorities in public school classrooms and interrogate how their own identities impact their teaching,” Robertson says.

SOE students have already begun developing seeds for units based on UMMA's collection objects. In conversation with museum docents, students discussed how they might incorporate art into assessment (especially for pre-readers), how they encouraged students' identity exploration, as well as promotion of Social/Emotional Learning and Learning for Justice principles.

Teaching with Art for Equity will be promoted not just to teacher candidates, but to those across campus who may wish to work in quasi-educational roles outside of public-school classrooms, such as arts organizations and after-school programs.

“These courses have the potential to reach a vastly wider audience of students who want to advance equity within the organizations they are a part of,” says Robertson. “This project speaks to a national conversation around the disconnect between educators and learners’ identities. It attempts to reduce the harmful implications of that divide by valuing BIPOC educators’ contributions to action research projects and curriculum development.”