A New Center at The School at Marygrove Reaches In, Out, Around, and Beyond to Advance Justice

Clinical Assistant Professor Alaina Jackson and English teacher Bayan Founas launch the REACH Center

Alaina Jackson (AM ’12, PhD ’18) joined The School at Marygrove (TSM) in 2021 as the Educational Justice and Culture Coordinator, just as the school was returning to in-person learning after the COVID shutdown.

“Our understanding of what schools needed to be and do had shifted,” Jackson recalls. “When I was hired, we knew there was going to be some work to do on the ground when it came to culture. We allowed ourselves the space to figure out what that would mean—to be responsive to this community and its needs.”

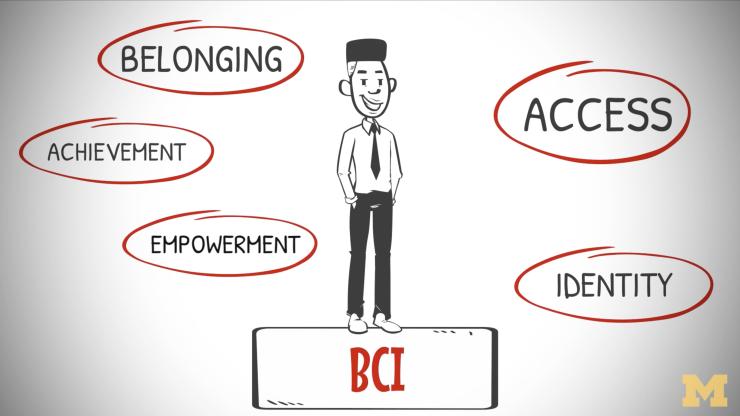

With a background in restorative teaching practices, Jackson’s goal was to create a center in the high school that would serve as a community hub. Jackson describes restorative teaching practices as those that “support all members of the school community to build and repair relationships (when harm has occurred) centered on care, respect, and open communication.” This year she and Bayan Founas (AB ’14, AM ’19), 10th grade English and creative writing teacher at TSM, founded the REACH Center, which opened its doors in September 2023 with the aim of holistically supporting school culture and climate through a restorative justice and culturally responsive lens.

“I’m really passionate about understanding what it means to practice justice in ways that feel tangible, and in ways that actually impact students’ lives,” says Jackson, who is also a clinical assistant professor of educational studies at the Marsal School. “We are intentional about the REACH Center being a space that's not your traditional classroom with desks. There are beanbags and alternative seating, and we have interactive elements on the walls for folks.”

Open each day at lunchtime, the REACH Center offers students an alternative outlet to the cafeteria, which Founas notes can be over-stimulating. “It gives them somewhere to bond with other students, get away from the day, hang out, and relieve some stress.”

The REACH Center’s mission is dedicated to building a school environment filled with student joy, history, celebration, support, and culture. This is achieved through the use of restorative practices and transformative activities that seek to dismantle stereotypes of Black and Brown kids in schools.

The center focuses on four goals: reaching in, reaching out, reaching around, and reaching beyond. In terms of reaching in, the REACH Center aims to develop a critical consciousness and awareness that equips members of the school community to interrogate the world around them. Reaching out entails creating and experiencing opportunities for mentorship and connection. Reaching around means the center engages in responsibilities toward the collective struggle against racism and all forms of oppression and injustice within schools and within communities both near and far. Reaching beyond conveys how the center challenges participants to imagine the possibilities of a more just, humane, and equitable school and world.

The center aims to help teachers and staff build restorative practices into their teaching and the culture of the school. Each Monday, in the principal’s weekly email to faculty, Jackson and Founas include tips on ways to achieve this. “It’s quick strategies they can use during the week,” says Founas. “We try to make it as light a lift as possible.”

During its inaugural months, the REACH Center focused on providing opportunities for members of the school community to transcend the traditional student-student or student-teacher relationship. Through its “Mondays at the REACH” lunchtime series, the center offered programming such as trap yoga, game sessions, karaoke, and gingerbread house decorating. During the month of November, the center celebrated the 50th anniversary of hip hop by honoring the genre’s often overlooked non-male voices as part of their Eats and Beats series. In February, the REACH Center supported a student-led committee that organized a series of events for Black History Month. The lineup of offerings included a Black Lives Matter at School week of action, a spirit week highlighting both historical and contemporary aspects of Black heritage, and a Divine Nine HBCU Day that brought in people from outside the school to build community. The month concluded with a dynamic showcase of performing arts and awards.

On behalf of the REACH Center, Founas instituted “Basketball Fridays” during lunchtime. Participation in the lively games—which is conditional on punctuality to class—has become an incentive for students to “work on their professionalism with school,” she says. Since TSM’s sports activities take place at neighboring Mumford High School, the informal basketball games on Fridays have become a cultural beacon for the entire high school to get together on their home court or cheer from the stands.

“Everyone is just in a good, positive mood,” said Founas. Although she initiated the activity, the students have since taken the lead. “I’m there to supervise, but they really facilitate the games. You see good sportsmanship, and it’s great to see them take leadership of it themselves.”

As part of its restorative justice mission, the REACH Center’s activities center joy. “Black kids don’t get to be children,” says Jackson. “They are expected to act and engage in ways that are adult. But they’re not pre-adults, they’re adolescents. They are children and should experience all the freedom and fun and joy that comes with that. Joy is not some add-on. Joy is a central, pivotal part of the work that we do. We’re trying to fight oppression in order to experience the joy that our humanity deserves.”

Early in the school year, the center put a call out to the student body asking for students interested in mentoring. Since then, “Husky Helpers”—named after the school’s mascot—has become the center’s flagship initiative. Each Wednesday, TSM high schoolers go over to the elementary school to offer support during lunch hour and recess. The high schoolers lead a group of younger students in a variety of activities. Most importantly, they’re an extra set of caring eyes and ears.

“These interactions offer support for students’ emotional development,” says Jackson. “The Husky Helpers talk about how important it feels for them to be able to be there at a time when they felt like an elementary student needed a helping hand or needed someone to just say, ‘Hey, how’s your day going?’”

The benefits go both ways. Jackson says the younger students’ enthusiasm for learning inspires the high schoolers to keep coming back. “The younger kids’ excitement about the things they’re learning empowers our high schoolers to remember that school can be a place where you are excited about learning.” The reciprocal nature of leading and learning that she sees between the older and younger students “shatters this idea that learning only flows one way, or from particular bodies. That’s justice work.”

The REACH Center is also cultivating events at the Marygrove Early Education Center on campus. In April they honored National Poetry Month and National Arab American Heritage Month, in May they focused on activities relevant to Mental Health Awareness Month as well as social activism. In June they will celebrate the successful completion of the school year. For Jackson, these intergenerational student relationships embody the P-20 vision of a cradle-to-career campus.

“I think that the students who are drawn to Husky Helpers might also be students who will ultimately have an interest in education,” says Jackson. “My dream is to connect the Husky Helpers with even more opportunities to see themselves as educators, to foster that passion within them to see this as a career option. For a lot of Black students, teaching is often not seen as a viable option—and that’s for a lot of reasons. But we also know that we need more Black educators. I see this as an opportunity to cultivate within them a passion for a broader understanding of the field of education.”