Could AI Help Children Get More Out of Educational Television Programs?

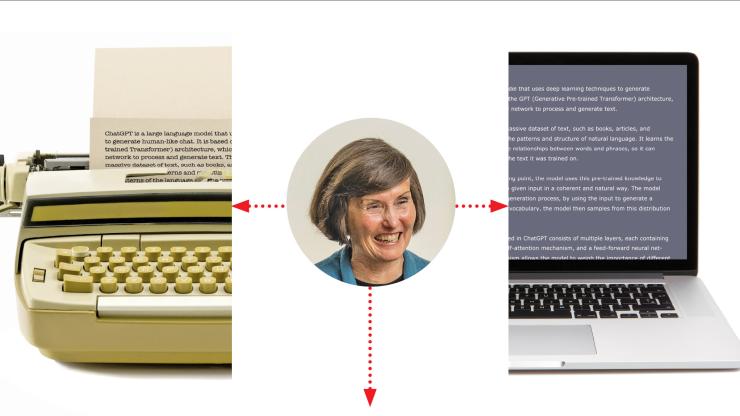

Assistant Professor Ying Xu explores possibilities introduced by conversational AI

According to a national survey, Assistant Professor of Educational Studies Ying Xu notes that children in the U.S. spend an average of two hours per day watching television or online videos.

“There are a lot of debates and worries about children using digital technologies. In my projects, we’re not trying to increase the time children spend with technology. But what we could do is think about the time children are already using technology. How could we make the technology a better learning tool for kids, and maximize their learning during the time that they are already spending, for example, watching TV or playing video games?”

Xu, who has a background in linguistics, has long been interested in the ways in which our acquisition of language can be supported by technology. While interning at a digital publishing company that developed educational media to teach kids English, Xu was responsible for observing how children interacted with the company’s products. She took note of how much the children enjoyed the media and what they learned from their interactions. Based on what she gathered, Xu drafted recommendations for the product design department to improve the products. Soon, however, she saw the limitations of exploring the potential posed by technology in the corporate sector. To further explore this line of inquiry, she went on to pursue her doctorate in Language, Literacy, and Technology at the University of California, Irvine.

In her early research observing children’s use of a range of different media—like televisions, e-books, and touchscreen games—Xu determined that children benefit more from media use if they are prompted by an engaging individual who asks them questions and listens to them reply, or when the content is specifically designed to encourage them to talk.

“When devices like Amazon, Alexa, and Google Home were introduced to households, I immediately recognized the potential for the technology to simulate the way a teacher or parent would engage young learners in educational dialogue,” Xu says. She conducted preliminary studies which showed that children could learn from their conversations with AI. “At that time, not a lot of people were aware of this potential for conversational AI. I thought it would be beneficial to find a partner who has already produced high-quality media and see how we could use AI to enhance how much children could learn.”

Since 2018, Xu has collaborated with PBS KIDS and a team of colleagues to study the impact of AI-enhanced children’s television programs. Building on shows like Dora the Explorer and Mickey Mouse Club House, which have pauses in their scripts for children to respond to the characters, Xu wanted to see how they could use AI to make the characters interact with the children based on their answers to questions. Because many children watch TV shows on mobile devices now, Xu saw an opportunity to incorporate conversational AI into the program by utilizing a device’s microphone.

Xu and her team created an interactive version of the PBS KIDS program Elinor Wonders Why, a science show for preschool-aged children. In their version, a curious bunny named Elinor listens to the responses young viewers give when she poses questions. She can reply with feedback specific to a child’s answers, or provide prompts if the viewer needs assistance.

“We know that children admire their favorite TV characters and may even form emotional attachments to them,” says Xu. “What if the character could actually listen to them and talk back to them? It means a lot to kids.”

In a study Xu and her colleagues presented at the 2023 American Educational Research Association (AERA) annual meeting, they divided 240 children into three groups. One group watched the fully interactive, AI-enhanced version of Elinor Wonders Why, the second watched the original non-interactive broadcast of the episode, and the third watched a semi-interactive version similar to a show like Dora the Explorer, in which the character poses questions, pauses as if listening, and then provides generic responses.

After watching the show, the researchers tested how much children had learned using an assessment developed by the team. The children who viewed the fully interactive episode performed the best on the assessment questions, followed by the group who watched the semi-interactive version and then those who watched the original non-interactive episode. Additionally, Xu’s team looked at the children’s responses to the questions Elinor had posed during the episode. The participants who watched the semi-interactive version lost interest in responding to Elinor’s questions when they realized she could not comprehend their answers.

In February 2024, PBS KIDS launched a new program, Lyla in the Loop to engage a broader range of children—this time ages 4–8—in STEM education. Over the last year and a half, Xu’s team has been working closely with the show’s creators and PBS KIDS to see how they could adapt it to incorporate AI to facilitate student’s interactions.

“There are a lot of design considerations that you need to think about: how to ask the best questions, how to facilitate students’ engagement if they are a little more hesitant to share their thoughts. And if we identify those who have misconceptions about a question, how do we scaffold those students?” says Xu.

Once all of the design aspects were taken into consideration, Xu and her team began to test the content with kids. In the first phase of testing, they just wanted to see if their design worked or not.

“It’s what we call a participatory design phase. We sit down with a group of five to 10 kids and show them our interactive videos. We just observe how they interact with the conversational AI.” They also ask the children questions: What do you like about this process? Was it confusing? Do you have any ideas that could help us make it even better? Xu’s team took the kids’ responses into consideration to continue improving the conversational video.

In the second phase of testing, the team will run a randomized trial with a larger number of children—200–300—dividing them to watch the same content in different formats as they did when testing the efficacy of AI enhancement to Elinor Wonders Why. As with the first program, the topic of Lyla in the Loop is STEM-related, with episodes that teach computational thinking. However, this new program will be offered in both Spanish and English.

The majority of the children Xu and her team work with are bilingual learners who do not speak English at home. They have found that these students benefit from the AI-enhanced programming to a greater extent because the scaffolding it provides helps them better comprehend the scientific concepts being introduced in the shows.

“We have learned that kids feel comfortable interacting with the AI that is more consistent with their language background,” says Xu. So do their parents. The finding inspired Xu’s team to see if they could make conversational AI more inclusive. We are interested in code switching—allowing the conversational AI to understand the mixed use of multiple languages. Multilingual children often switch between different languages based on the situations and the context and who they’re talking with.”

In collaboration with the Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop, Xu is exploring how a Spanish-English bilingual AI could support parent-child interactions during storybook readings in Latine families. From interviews with both the children and the parents who tried the bilingual AI, she found that participants appreciated the flexibility to engage in both languages. In fact, it inspired parents to think about the overall importance of cultivating their child’s bilingual and bicultural identity.

Xu is also keen to see if, by facilitating the meaningful interactions between children and their favorite TV characters, they might come to see the characters as role models for learning STEM. In Lyla in the Loop, the main character is an African American girl. “We’re very curious to see if having a dialogue with Lyla will become a factor in encouraging girls and those from minoritized backgrounds to become scientists.”

Furthermore, Xu hopes to determine whether having a dialogue with AI could help kids not only learn about the concepts introduced in the show, but also transfer that knowledge to different scenarios. “This is one thing that we think is very important,” she says, “because learning is not just memorizing a concept, but also actually being able to apply it in everyday problem solving.”

Xu and her team have received two National Science Foundation (NSF) grants to support their research with PBS KIDS. Much of her previous research had an emphasis on participatory design, using feedback from children, parents, and teachers to inform different iterations of the media she and her colleagues develop. However, with the advances in generative AI, Xu is interested in extending this user engagement beyond the design phase, allowing kids and educational stakeholders to continuously customize and influence the media content as they use it. She is now working on a new project (also funded by the NSF) to empower non-technical experts who know children best, like teachers and parents, to use AI to generate learning sources for children.

“We are designing AI that allows teachers to ‘collaborate’ with it to embed meaningful learning questions into educational videos,” she says. “This approach allows teachers to tailor AI-generated questions to fit their specific instructional needs, rather than relying solely on predeveloped content.” Xu’s team is conducting interviews with teachers in different states and has found that educators are generally excited about the potential of AI to improve their instruction, especially when they have adequate control over the content and its application.

When Xu is met with resistance to researching the potential uses of AI in early and elementary education, she understands parents’ and teachers’ skepticism. But she is also ready with an answer.

“As researchers, it is actually our responsibility to understand the implications of AI on child development before the technologies reach children at a massive scale,” says Xu. “We need to stay ahead of the curve and think about what kind of impact this technology could have on children’s cognitive development, social emotional development, and physical health. It is our job to understand this better so that we can provide guidance to facilitate the future development of the technology in a way that is safe and inclusive for children.”