Teaching Writing in the Age of Generative Artificial Intelligence

Anne Ruggles Gere reflects on recommendations from the university’s Generative Artificial Intelligence Advisory Committee

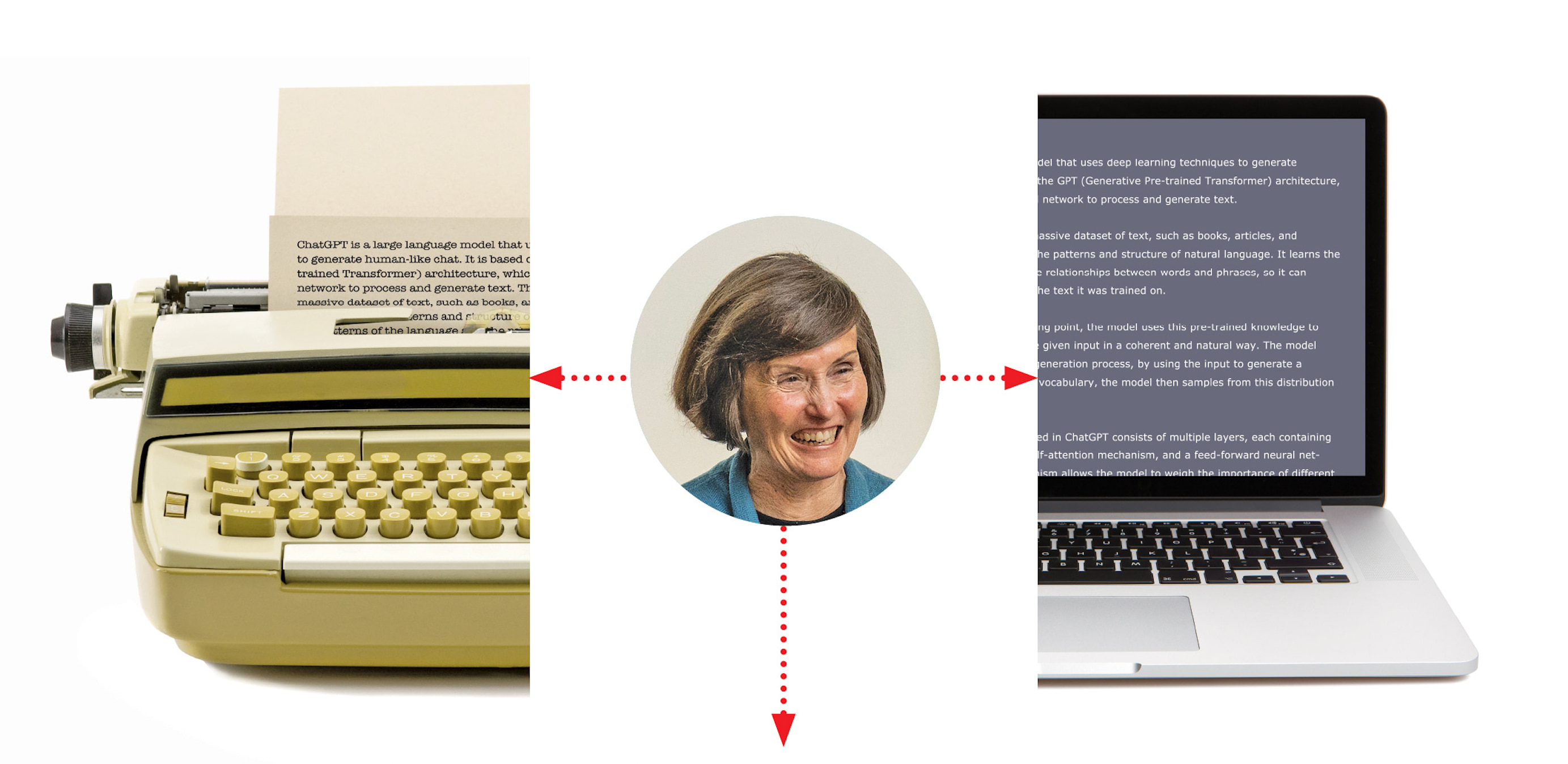

Over the course of her 30-plus years as a professor at the University of Michigan, Anne Ruggles Gere (PhD ’74) has borne witness to seismic changes in the way we write and teach writing. A professor of English and Education since 1987, she has served as chair or co-chair of the Marsal Family School of Education’s Joint Program in English and Education since 1988. From 2008 to 2019, she directed the Sweetland Center for Writing, a comprehensive writing center that exists to support student writing at all levels and in all forms and modes.

Gere remembers producing her dissertation on a typewriter. And she remembers the way the introduction of computers changed student writing. Before computers, she recalls, the most common mistake was misspelled words; with the advent of computers—and their spell check programs—the most common mistake became misused words. (Think ‘their’ instead of ‘there,’ ‘to’ instead of ‘too,’ or, to Gere’s delight—when referring to one’s demons—‘exercise’ instead of ‘exorcise.’) She was teaching at the dawn of the internet, and this year—in her final two terms before retirement—she found herself teaching in the age of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI).

In early 2023, as the emergence of GenAI programs like ChatGPT began to spark concern throughout institutions of higher education, Provost Laurie McCauley and Vice President for Information Technology and Chief Information Officer Ravi Pendse announced the formation of an advisory committee to recommend how the university should approach the evaluation, use, and development of emergent GenAI tools and services. Gere was asked to join. She knew colleagues who had declined, but she felt compelled to add her voice.

“I agreed to join the committee because writing studies is my field,” says Gere. “And frankly because when I looked at the composition of who was already on the committee, nearly all male, nearly all from the sciences and engineering and medicine, I thought they needed somebody from the humanities, somebody who’s a teacher—all the things that I value that I wasn’t sure would be heard if my voice wasn’t there.”

Consisting of faculty, staff, and students from across the university, the Generative Artificial Intelligence Advisory (GAIA) Committee worked to create resources for the university community to handle the impact of GenAI programs, provide training and support infrastructure for the use of GenAI tools, and study its longer-term implications for work and life at U-M. The body was tasked with devising a report that would set the foundation for the university’s path forward with GenAI in the short, middle, and longer terms.

“I think it’s fair to say that many of the people on the committee were very positive and excited about the potential for generative AI,” says Gere, whose own bias tilted in the other direction. “What I pushed for was more about what effect this is going to have on the University of Michigan’s teaching mission and on the people who are doing the work of teaching. My major contribution—in addition to talking a lot about writing with people who don’t think about it as much—was to design and carry out a survey.”

The survey, which was shared with faculty, students, and staff across the university in early June 2023, was designed to help the GAIA Committee make recommendations that would allow the university to maximize GenAI’s potential benefits.

With over 6,000 responses, results from the survey confirmed Gere’s sense that there are as many possible downsides as upsides from the adoption of GenAI. The results showed that of the three groups surveyed—staff, faculty, and students—staff had the most negative feelings about GenAI. This group was worried about job security. Faculty were most concerned about academic integrity.

“Undergraduates were most enthusiastic, which was not surprising because I think they are much more comfortable with technology than probably any other group on campus,” says Gere. “What I found interesting was that they also had a strong negative response because they feared they would be falsely accused of cheating. That sort of weighed against their enthusiasm.”

As McCauley and Pendse state in an introduction to the report, “GenAI is shifting paradigms in higher education, business, the arts, and every aspect of our society. This report represents an important first step in U-M serving as a global leader in fostering the responsible, ethical, and equitable use of GenAI in our community and beyond.” The report is meant to be used as a catalyst for conversation as GenAI technology—and the university’s adoption of it—continues to evolve. The report spans topics including an explanation of the science and capabilities of GenAI; guidance for instructors; the impact and management of GenAI on teaching, learning, and research; ethics and equity; training resources; and ongoing academic research on GenAI. Additionally, the report anticipates the impact GenAI will have on campus life, offers examples to instructors for how to create dynamic assignments, and explores the positive and negative effects GenAI may have on the university community.

Of the many recommendations and guidelines outlined in the report, Gere was most pleased by two decisions the committee made. First, that the university should create its own version of ChatGPT—U-M GPT. Gere frames the recommendation as an equity issue—whereas anyone can access the free version of ChatGPT online, not all students would be able to afford subscribing to the latest and best version of the tool. That would create an imbalance of access among the student body. U-M GPT would also address the security implications posed by the GenAI tool that is widely available. “It prevents the work of our students from being used to train and advance the larger GPT,” says Gere.

The other decision she commends is choosing not to rely on detection tools to check whether or not student work has been created by GenAI.

“The detection game becomes an arms race very quickly. Nobody wins,” says Gere. “Perhaps more importantly, it changes the relationship between students and teachers. I do not see myself as a police officer in the classroom, and I don’t ever want that role. I see myself as an enabler who’s going to try to help people develop into the best writers they can be. And it seems to me that playing police is exactly the wrong way to do that.”

When Gere addressed the Marsal School community at Fall Convocation in September, she shared examples from her own teaching practice for how to navigate the use of GenAI tools with students. One of the most common assignments given to K-12 and college students is to write an essay about a given topic.

“That is truly a terrible assignment,” said Gere, “and it’s perfect for GenAI. ChatGPT can write essays. They’re not very good essays, but it can write essays. As teachers, if we care about the quality of student writing, I think we have to think long and hard about the quality of our assignments.” She suggested including features in assignments that have students address the audience to whom they are writing and the purpose for which they are writing. “It seems sort of simple, but let me tell you, assignments don’t often include those features, and that can make a huge difference.” Another approach Gere suggested was requiring the submission of iterative drafts throughout the semester rather than turning in one big paper at the end of the term. “If we are asking students to write multiple drafts, and providing feedback as those drafts are being produced, they can’t win with AI. Rather than simply assigning something and then waiting for students to turn it in, it seems to me part of teaching is intervening in that process in these ways.”

In the seminar Gere taught during the fall term, she had students use U-M GPT to generate ideas to get started on one assignment. For another assignment, she asked them to use U-M GPT to create a draft of a paper, and then use it as an object for revision. By articulating the weaknesses in the GPT-generated draft, the students were able to identify the elements that would make it a stronger piece of writing—adding specific details to make it less general, developing a clear and distinct voice—and in turn learn to incorporate those same tactics in their own work. Finally, she had students ask the AI to write a bibliography on any given topic. “Of course, half of what the tool generated were hallucinations.

“I’m trying to help students learn about what AI is,” continues Gere, “because I don’t think that just shutting the door is the answer. But figuring out what it can do and where it really doesn’t make sense to use the tool is useful.”

Gere says that more organizations—including the Modern Language Association and the National Council of Teachers of English—are stepping forward with findings from task forces convened to advise how to navigate the new moment we find ourselves in. In January 2024, Karthik Duraisamy, who served as chair of the U-M GAIA Committee, spoke about the university’s report at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland where members of the business world were as concerned about how GenAI will shift areas of industry as members of the U-M community have been about its impact on higher education. Although she’s impressed that the committee’s work is being shared with a broad audience, and glad that the recommendations of professional organizations are providing resources to teachers, as someone who has seen technologies come and go throughout her long tenure in the classroom, Gere remains somewhat hesitant about the dramatic effect some claim GenAI will have on teaching.

“If you care at all about student learning,” she says, “I don’t see how you could persuade yourself that just having students give directions to a machine is learning how to write. There’s so much more to learning than just the input of content.”