With the advent of social media, the world of our students has changed in so many ways. Rather than bemoaning that shift, let’s evolve to meet the students in front of us.

“All of us in the academy and in the culture as a whole are called to renew our minds if we are to transform educational institutions—and society—so that the way we live, teach, and work can reflect our joy in cultural diversity, our passion for justice, and our love for freedom.”

—bell hooks, Teaching to Transgress

Although bell hooks published this seminal work on education in 1994, I was astounded at how much of her struggles in the classroom mirror those of educators today. And while I remember reading it as part of my time in the Marsal Family School of Education, I would not have turned back to it for my problem of practice if not for my mentor on this journey, Dr. Kendra Hearn.

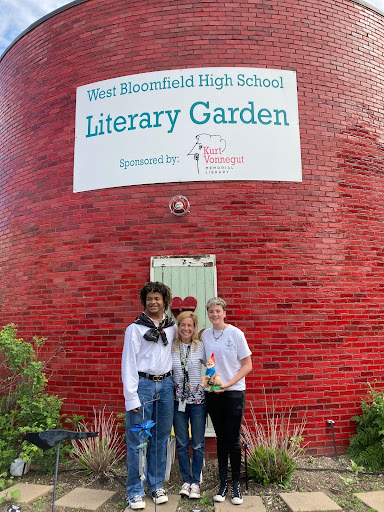

As I am connecting the past to the present, I must acknowledge that adding diverse texts to English classrooms is the very first conversation I had with Dr. Hearn when I met her at a job fair in the Michigan Union in the spring of 1999. At that time, Kendra was a rising star in the West Bloomfield High School English department and had accompanied the assistant superintendent to assist in selecting candidates for an opening at the high school. I do not recall what prompted our discussion, but the conversation that resulted has resonated with me throughout my 25 years at West Bloomfield High School (yes, I got the job!)

When we first began to discuss the complexities of choosing multicultural books to enhance our curriculum, our most pressing problems back in 1999 were funding, resistance from within the school system, and which texts to choose for what classes. In 2024, all three of these problems still exist, but now there is so much more to consider.

When I think about the reluctant readers in my classes, I realize that they are, in fact, reading—just not the course material. But is it the course material itself that is the only factor? I already try assiduously to provide a range of diverse texts and materials to my students, and yet many still do not want to read.

While discussing this apathy with my seniors before they graduated, one student noted that her generation was, quite possibly, the most literate generation in the history of America because of their phones. She pointed out astutely that students are constantly reading—just not what educators consider to be “valuable” or “rigorous” text. This made me think about our approach to English education in 2024 as a whole. hooks writes, “To teach in varied communities not only our paradigms must shift but also the way we think, write, speak. The engaged voice must never be fixed and absolute but always changing, always evolving in dialogue with a world beyond itself” (11).

One of the ways we need to rethink teaching English, I believe, is by expanding our definitions of text, value, and rigor. It is not enough to simply add books to the American literature curriculum written by a range of multicultural authors, nor do most students in my classes have the attention span to read a novel for a sustained period of time without picking up their phones. Between the distraction of the phones and the struggle to regain skills lost during the pandemic, it has become harder and harder to teach the way I did just five years ago. Our world has shifted, and rather than bemoaning that shift, I believe we must heed hooks’s wisdom and evolve to meet the students in front of us. Texts are so much more than novels; they include the very “texts” students write to each other that are often in an incomprehensible shorthand (replete with emojis) that many adults often dismiss as gibberish but which are packed with sophisticated meaning. Texts include YouTube clips, films, animation, graffiti, works of art, graphic novels, cartoons, advertisements—so many of which we can find ringed around our football stadium and within our school walls!—social media posts, articles, maps, charts, body language, website graphics; I cannot possibly name them all. Are those texts valuable? Do they provide rigor? Yes and yes; with critical thinking skills, absolutely.

Not only do students need to see themselves reflected in the texts we choose for our classes, but we must also include them in the process of choosing those texts. hooks notes,

[Students] do want knowledge that is meaningful. They rightfully expect that my colleagues and I will not offer them information without addressing the connection between what they are learning and their overall life experiences.

This demand on the students’ part does not mean that they will always accept our guidance. This is one of the joys of education as the practice of freedom, for it allows students to assume responsibility for their choices. (19)

Dr. Gholdy Muhammad builds on hooks’s work in her 2023 book, Unearthing Joy: A Guide to Culturally and Historically Responsive Teaching and Learning, in which she urges educators to design curriculum by first getting to know the students in front of them. Without student input—and by input, I do not mean test scores and demographics—but by asking students themselves what they want to learn about. Muhammad writes, “This question is important because the answers give us authentic purposes for teaching. We cannot teach themes, topics, or texts simply because they’re in the ‘textbook’ or ‘program.’ We must study curriculum to ensure that learning experiences reflect the needs and identities of our students” (124). She provides a list of questions educators can use or adapt to better learn what motivates, interests, and frustrates students, as well as how they see themselves in the world (how do they choose to identify themselves, and in what ways?) and what brings them joy (126–129). I especially love that last question, as it speaks to one of my questions from my first blog post. If I know what brings my students joy, I can incorporate even more ideas into my classes, whether in the texts, discussions, assignments, celebrations, motivators, assessments, and environments to further diversify my teaching.

As I reflect on my own teaching practice and think about ways to diversify my American literature curriculum, I have realized that I need to begin this fall with more questions than answers. I need to spend the first precious days of the school year not just building our classroom culture and creating a team spirit in the class, but to structure my time in such a way that I am meeting with students individually and getting to know them, as well as giving students the opportunity to get to know each other. In addition, as hooks notes,

When education is the practice of freedom, students are not the only ones asked to share, to confess. Engaged pedagogy does not seek simply to empower students. Any classroom that employs a holistic model of learning will also be a place where teachers grow, and are empowered by the process. That empowerment cannot happen if we refuse to be vulnerable while encouraging students to take risks. (21)

That will mean more sharing of our individual stories (I use Narrative 4’s Story Exchange in my classes as a Narrative 4 Fellow), continuing to dismantle outdated power imbalances, providing more mentor texts for relevant, real-world writing, and letting go of assumptions of what we “should” read. As students struggle with questions of societal problems and social justice issues that bedevil us in West Bloomfield, metro Detroit, the state of Michigan, and across the nation, I can work with them to show how so many of these have their roots entrenched in the narratives of the past. What is most exciting to me is to hear what my new students want to learn about—this will be a year of surprises, changes, and hope for all of us as students connect their lives to a wide range of texts and are given opportunities to pursue their passions with joy and freedom.