The Teacher Hierarchy of Needs

For many years, we have advocated approaches to schooling that address all of a child’s needs in order to give them the best opportunities to learn. For example, a child who does not have enough nutrition will not be able to focus through a long school day. A child who needs vision correction will have trouble reading the board. A child who experiences violence may be preoccupied with fear and grief. We have long recognized that a child’s basic needs must be met before schooling will be productive. This moment is no different though the trauma experienced by students, parents, and educators is more broadly felt.

Our Center for Education Design, Evaluation, and Research (CEDER) team developed this model to help everyone we serve focus their efforts where they are needed in this difficult time. If you have been struggling, you are not alone.

We are here to support you with what we know best—teaching and learning—but first we must acknowledge that the foundation for successful teaching and learning, as displayed in the hierarchy graphic, is strongest when the physiological needs of teachers, students, and their families have been met. Whether you are a teacher making a big transition to distance learning or a parent trying to homeschool while balancing many other responsibilities, lead with a focus on your needs and those of your children or students.

We can’t expect what we do right now to be a perfect replacement for school, but we can still keep kids engaged, growing, and learning. We are here to provide supports or guidance for teaching and learning at this time. Please submit your questions using our Ask an Expert form, connect with other educators online, and tap into U-M resources.

Teacher Hierarchy of Needs

Providing online instruction and other forms of learning at a distance is important but should be viewed in the broader context of multiple,

intersecting needs. Online instruction and distance learning will be more effective and productive when we take care of ourselves and do

what we can to support our students and families.

Provide online instruction or learning at a distance

Help your

students feel safe

and connected

- Provide support and connection

- Show students that someone cares

Feel safe,

connected, and loved

- Take care of your emotional health

- If you feel overwhelmed, take care of yourself

- Be there for your family and friends (in safe and responsible ways)

- Let your family be there for you

Meet the physiological needs of your

students and their families (health,

food, shelter)

- Districts might provide resources and referrals, if necessary

- Students shouldn't be expected to work if they are not safe

- This may be out of your control

Meet your own physiological needs

- Staying safe, having food and shelter

- You can't help others if you are not safe

- Use physical distancing as much as possible

Ask an Expert

Ask an Expert Responses

- What might parents be doing with their children at home to support their learning using technology tools?

-

Dr. Liz Kolb, professor of education technologies, shares 6 tips with parents about supporting their children's learning from home during the COVID pandemic:

- What should screentime look like during the COVID pandemic?

-

Dr. Liz Kolb, professor of education technologies, shares 7 tips with parents about children's screentime, including information on different kinds of screentime, how to get the best learning results, and how to take breaks from technology:

- How might teachers use technologies to maintain learning continuity?

-

Dr. Liz Kolb, professor of education technologies, shares 7 tips with teachers about what they should be asking their students do with technology during the COVID pandemic:

- How can educators provide small group literacy instruction for young children using video conferencing platforms?

-

In this video, Nell K. Duke discusses how to provide small group literacy instruction for young children using a videoconferencing platform (Zoom). She walks through a phonics lesson focused on oi and then, more briefly, a lesson that builds knowledge about food chains and flow diagrams. The video concludes with reflections from four instructional coaches and a few final words from Duke.

- Looking ahead to the possibility of continued remote teaching and learning in the fall, what guidelines would help classroom teachers design "right-sized" lesson/learning chunks for students of various ages to complete asynchronously over the course of a week?

-

As teachers know, this can be a challenging question even in a traditional classroom setting so it may take some time to pinpoint exactly how to plan your students’ time. While much depends on the age of the learners, how familiar students are with the content being taught, and the nature of the activities planned, Dr. Liz Kolb and Dr. Rebecca Quintana offer some suggestions and tools for planning “right-sized” lessons that will take place remotely.

- If you are doing any synchronous classes, keep in mind that you want to focus on "high touch/complexity" content for the synchronous classes and "low touch/complexity" content for the asynchronous. Figure out where your students mostly get confused or struggle and use that for the synchronous content.

- It can be helpful to provide structure in advance for the synchronous interactions that address high touch/complexity content. For instance, you could ask students to submit an exit card at the conclusion of each day or week through a Google form. You could ask questions: What have been the most useful or meaningful ideas you have learned today (this week) and why? What questions do you still have about what you learned today (this week)? You could use this information to target areas where students need additional support.

- Tips for asynchronous learning

- Avoid busy work, make sure each activity is purposeful and provide feedback on everything (encourage peer to peer feedback when possible and safe).

- Create a weekly module in your Learning Management System that you share on Fridays or Sunday (not Monday morning because that can overwhelm/frustrate caregivers who may be planning for the week on a Sunday).

- Include explicit video and text instructions/guidelines for how you recommend the children navigate the weekly module to complete activities. I recommend using a hyperdoc approach (where you include all activities in one Google Slide Show or Google Document in order of what makes the most sense to do first, through last).

- Additionally, you could create a visual of the ways that students will interact with the instructor and with subject matter in the course. Here’s an example from Twitter.

- You can make one per subject if you are teaching at the elementary level but don't make more than 3 per week.

- Include choice and voice in the hyperdocument.

- Give a choice of content take up—such as two ways to learn the same content, like two different movies or a movie or reading.

- Give choice of how to show what they know—such as share on a discussion board, record an audio recording, or draw a picture and upload it...etc.

- Include timestamps on the hyperdoc (how long you expect the children to spend on each activity, such as "this activity should take 15 minutes"), thus children can also select an activity based on how much time they have in the moment. If you can, test the times by doing the activities yourself and then double that time as your timestamp (that is usually how long it will take your students to complete).

- K-1 The time to complete everything should take no more than 1.5 hours for the whole week.

- 2-3 The time to complete should take no more than 2.5 hours for the whole week.

- 4-5 The time to complete should take no more than 3.5 hours for the whole week.

- 6-8 The times should take no more than 4 hours for the whole week (per subject area).

- 9-12 The times should take no more than 5 hours for the whole week (per subject area).

- Include ONE collaboration activity each week in the module such as discussion boards, collaborative video editing (you can use Video Ant or ReClipped), collaborative corkboards like Padlet, discussion tools like Parlay, or even a Google Doc/Spreadsheet that all students share out on.

- For collaboration activities, it is good to include structure in advance. You could prepare a set of questions that students should consider prior to the session and then they can use this as a guide as they work through specific concepts together.

- Having a tangible artifact like a Padlet is a good outcome for these kinds of activities. It is a good idea to ask one student to summarize the outcome of the collaborative activity. They could send the teacher a summary or this could be shared through a Google doc that is visible to all students. This responsibility should rotate.

- Avoid introducing too many new technology tools at once. Instead, introduce new tools slowly over time (1 new tool per weekly module). Try to repeat old tools, rather than always using new ones.

- Only use district approved technology tools where students have to login (check with your district on this).

- Consider having a time where you, the teacher, are available for drop-in chats through ZOOM so students know they can come and ask for help or just chat. Depending on how “popular” this is, these sessions could be structured around subjects and special assignments.

- Another idea is to form “pods” at the start of the year where students progress through the class together. This could help students feel connected to others in the class. During synchronous sessions, these “pods” could be the basis of groups formed.

- If you are doing any synchronous classes, keep in mind that you want to focus on "high touch/complexity" content for the synchronous classes and "low touch/complexity" content for the asynchronous. Figure out where your students mostly get confused or struggle and use that for the synchronous content.

- How can teachers promote productive discussions in remote environments?

-

Response from Jeff Stanzler, director of the Interactive Communications & Simulations (ICS) group and lecturer in educational studies:

- In a time when we can't teach college courses as most faculty were accustomed, how might professors evaluate students? How has grading changed? How might we think about balancing the rigor of a university program with the flexibility required by our current circumstances?

-

Response from Dean Elizabeth Moje:

First, I’d like to acknowledge that it is extremely difficult for both faculty and students to move from face to face to online education. Syllabi that were designed to be taught in person do not translate seamlessly to virtual or asynchronous settings. It is important to be flexible with ourselves and our students. At the University of Michigan, we chose to move to a “pass/no record COVID” system of grading for Winter 2020 with the belief that taking letter grades off the table would reduce pressure and allow students to focus on their learning.

The questions posed here are exactly the right questions to be asking at this time, and in fact, we are all eagerly awaiting some definitive research on these very issues. Because this is an unprecedented—but perhaps not one-time—experience, the world is going to need answers drawn from evidence to guide our work into the future.

Your questions call for both small-scale, qualitative studies of how faculty members and students are navigating through these challenges and large-scale survey studies that document and describe the most typical approaches to

- instruction (e.g., Synchronous or asynchronous? Blended approaches? Use of breakout groups? Chats? Extended reality tools?),

- assessment (e.g., Proctored examinations? Projects? Synchronous presentations? All of the above?), and

- evaluation (e.g., Do grading policies shift? How is participation evaluated? What does it mean to “attend class”?).

These and many other questions will be the education research questions of our time. In particular, we in the Marsal Family School of Education are intrigued by questions of what is gained and lost in remote teaching environments. What can be done more effectively? What teaching does not—and never should—translate to remote teaching? And what is the added value of residential, face-to-face instruction? The education world, from preK to postsecondary and graduate education awaits our research-based responses.

- What might parents whose children have IEPs do to effectively work with their students’ educators in these circumstances?

-

Response from Kathleen Fortini, lecturer in teacher education:

During this unprecedented time, it is important for families and educators to work collaboratively to support each student. Having clear and consistent communication between home and school will help to optimize learning. As a family you might consider the following practices to structure learning at home:

- Set up a schedule that works best for your family and establish a home school routine

- Consider creating a checklist of tasks with your child and their teacher

- Take breaks as needed

- Build off your child's interests to explore meaningful learning opportunities

- If the students' Hierarchy of Needs is not met what is our next approach?

-

Response from Darin Stockdill, Instructional and Program Design Coordinator, Center for Education Design, Evaluation, and Research (CEDER):

When needs outlined on the hierarchy of needs are not being met, whether they be teacher or student needs, we do the best we can to help others get those needs met. So if a student comes to school hungry, we send them down to the cafeteria to get some food (if possible) or give them a snack from our closet. If they don’t feel safe at home and they share this with us, we refer them to the school counselor or social worker.

In schools that lack resources and effective student support systems, this can be a difficult process, and this lack of supports can create a lot of stress for teachers who really want to help their students. In these situations, we do what we can, while also recognizing that we have our own needs and have to engage in self-care. We have to recognize that self-care is not selfish, but rather it enables us to be prepared to support others. Where support for students is lacking in school systems, teachers can choose to take the time to learn about community resources and make suggestions (not referrals or recommendations) to students.

We have to recognize our limits in this process and take the actions we can that are meaningful. We can start by showing empathy, listening to students, and trying to make reasonable accommodations in the classroom to support their ongoing participation in learning. This might involve alternate assignments, extended deadlines, or alternative formats for assignments. We have to recognize that people—students and teachers alike—will not function well in teaching and learning environments when basic needs are not being met, and again, do the best we can with the resources we have to create supportive environments in our classroom.

For more ideas, check out this quick guide from the American Psychological Association, as well as this student support guide put out by the Michigan Department of Education.

Remote Teaching and Learning

#F2Ftovirtual

Professor Liz Kolb is an expert in education technologies. She has been gathering other experts who teach with technology and teachers just beginning to transition their teaching to online platforms to support one another. Join their conversation at any time on Twitter using #F2Ftovirtual. The group frequently holds Twitter live chats on Sunday evenings.

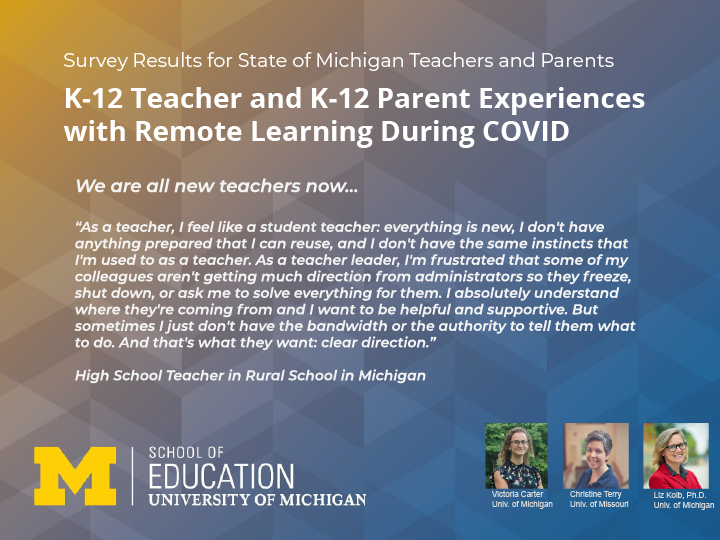

Teacher and parent surveys on remote learning

Clinical Associate Professor in the University of Michigan Marsal Family School of Education, Liz Kolb (study PI), along with Christine Terry of University of Missouri and UM SOE Research Assistant Victoria Carter, share the results of two surveys conducted during remote learning (as a result of schools closing because of the COVID pandemic) in the Spring 2020. The first study focuses on the experiences of K-12 teachers and the second study on the experiences of K-12 parent experiences during remote learning. Trends and discussions are included in the document. Please contact Liz Kolb with any questions at [email protected].

Liz Kolb reviewed the results of the survey during a free webinar on August 21, 2020. A recording of the webinar can be accessed here (Zoom login required).

News

Professional Development

The coronavirus pandemic has forced educators out of their classrooms and necessitated remote teaching and learning. How should pedagogies be adapted to effectively accommodate the technologies now required to reach learners? What can be learned now that will be applicable now and when schools are open again? The SOE offers several professional development opportunities that may help educators navigate the challenges presented by the pandemic, and prepare for what comes after.

Advanced Education Technology

The Advanced Education Technology Certificate Program develops educators who will use educational technologies for learning in meaningful and transformative ways. Learners connect ISTE competencies in this certificate program to their own P–12 classes and schools, creating lessons and professional development projects around their school's particular needs and demographics.

This course is online, contains synchronous and asynchronous coursework, contains 17.5 hours of content (over 15 weeks), and upon completion awards a professional, non-degree certificate and/or 45 SCECH hours.

Disciplinary Literacy

With instruction by Dean Elizabeth Moje and Darin Stockdill, Instructional and Program Design Coordinator, CEDER, learners in this course will study the latest findings and recommendations from working educators in the field of disciplinary literacy, and uncover tools, knowledge, and strategies needed to develop students' reading and writing capabilities in different disciplines.

This course is online, self-paced, contains 10 hours of content, and upon completion awards a professional, non-degree certificate.

MicroMasters

The MicroMasters in Leading Educational Innovation and Improvement is a series of courses designed to help educators become leaders in the practice of educational innovation. The five courses cover topics including leadership in teaching and learning, designing and leading learning systems, improving science in education, leading educational innovation, and more.

This program is online, self-paced, contains 10 months of content (2–4 hours per week), upon completion awards a professional, non-degree certificate, and can count as credit toward a Master's degree.

Teaching & Learning Exploratory

The Teaching and Learning Exploratory (TLE) features full-length classroom videos and curated collections of clips with integrated tools for interaction and exploration. The TLE includes over a thousand classroom sessions from diverse locations in K-12 settings.

TLE resources are online, and a limited number of clips are available free of charge. TLE resources are free for members of the Marsal School community.

Resilient Teaching Through Times of Crisis and Change

In the Resilient Teaching Through Times of Crisis and Change course, explore a range of teaching resources developed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, guide pedagogical decision making during ever-changing times, and learn how to build courses able to withstand changing conditions.

This course is online, self-paced, contains 25 hours of content, and upon completion awards a professional, non-degree certificate.

Fluid Continuity of Learning Using a Blended Approach

This self-paced professional development workshop is targeted at school district leaders interested in developing a fluid continuity of learning between school and home using a blended approach. The course includes resources, templates, checklists, and professional development packets to modify and use in K-12 schools.

This course is free, online, self-paced, and contains 5 modules of content.