Educators often have the best of intentions when updating their materials, but we truly need to stop and dig deeper when thinking about new texts, especially when we are attempting to add diverse texts from historically marginalized groups.

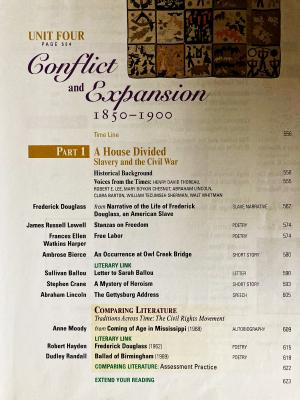

Last summer I had the opportunity to present at a local conference about Frederick Douglass. After 25 years of teaching American literature, he consistently remains a favorite for me, endlessly fascinating, the most photographed man of the 19th century (it’s true! check out the brilliantly curated American Writers’ Museum Exhibit). Since I am still teaching from the same textbook I started with way back in the last century when I also used a chalkboard, I was curious to see how Douglass was represented in new textbooks, knowing that at some point we would be able to upgrade our materials.

What I found in my search was mildly encouraging but mostly frustrating. No longer was Douglass relegated to the same passage from Chapter X of his Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, the famous fight in which he conquers the barbaric Edward Covey and writes,

It was a glorious resurrection, from the tomb of slavery, to the heaven of freedom. My long-crushed spirit rose, cowardice departed, bold defiance took its place; and I now resolved that, however long I might remain a slave in form, the day had passed forever when I could be a slave in fact.

However, despite all Douglass had done to escape enslavement, I noticed that the latest textbooks available continued to bury him in that very same “tomb” yet again. Twenty-five years later, this was progress in one textbook I found online: Frederick Douglass, from What, to the Slave, Is the Fourth of July? (nonfiction, 1852).

Yes! I was excited to see that Douglass was acknowledged as a poet (but only one poem? And based on a “slave spiritual” at that?) And while his scathing criticism of the Fourth of July has received an uptick of attention since 2020 (and rightfully so), I could not help but wonder why there was still no wider discussion of Douglass. I wondered,

- What about his relationships with Ralph Waldo Emerson and the Thoreau family? Scholars are still debating this, and some suggest his home at Cedar Hill can be considered his “Walden Pond!” is he also a transcendentalist?

- What about his lifetime advocacy for civil rights for African Americans and women? What about his political work with Lincoln and appointment as Minister to Haiti?

(For a broader look at Douglass’s extensive life experiences, see the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site)

Our teachers recently audited the English department’s curricula and made recommendations on ways we can update our materials. I can’t help but think about Frederick Douglass as an example of how educators often have the best of intentions when updating their materials, but how we truly need to stop and dig deeper when thinking about new texts, especially when we are attempting to add diverse texts from historically marginalized groups - and that means including more stakeholders at the table to share in that decision making process. I’ve been wondering lately:

- Why do we never start where we stand, on the land on which we teach? Do we think about our environment, the untold stories beneath our feet? Every time I hear a Land Acknowledgement Statement read, I wonder about the stories behind those tribes, all of the human beings who lived and loved and birthed and fought and died on this land, the ones who were forced off of it. What stories did they leave behind? What stories do their descendents have to tell us?

- Why, when we do choose texts, are they so often tragedies? My students have been asking that question for decades. Why do ELA educators so often choose texts that tend to showcase historically marginalized people portrayed in their greatest moments of pain and suffering? For example, I would argue that we deny Frederick Douglass the richness and fullness of his humanity when we reduce him to his enslavement. How can we involve more representation in this process - from students, from community stakeholders, from experts in our own buildings, from experts in the field?

- And finally, why can’t we choose texts that are inspirational and hopeful? Perhaps - dare I say it - humorous? Think about that for a second. How would that change students’ approach to their English classes if we broadened our idea of what text is, what texts are worthy of being read and studied, and provided bridges between the canonical and the contemporary? What if we challenged students to rewrite tragedies as comedies, to rewrite sorrowful endings and transform them into hopeful endings? What if we gave them the power to find the books that best represent them in all of their complexity in our American literature classes? What would that look like?

I’m really excited to find out!