The fight for Detroit school children’s right to literacy isn’t over, says Dean Elizabeth Moje

In the wake of a landmark decision by the U.S. Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals in April that declared Detroit school children have a constitutional right to literacy, Detroit families and education advocates around the country look to the Michigan Legislature to determine whether Detroit schools will receive the support necessary to combat the inequities recognized by the court.

This article first appeared in Michigan News.

In the wake of a landmark decision by the U.S. Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals in April that declared Detroit school children have a constitutional right to literacy, Detroit families and education advocates around the country look to the Michigan Legislature to determine whether Detroit schools will receive the support necessary to combat the inequities recognized by the court.

Arguing that literacy is a skill that gives students access to knowledge and allows them to become full participants in our democracy, the Gary B. v. Whitmer case cited the absence of qualified teachers, crumbling facilities, and insufficient materials as preventing Detroit public school students from accessing literacy.

Elizabeth Birr Moje, dean of the University of Michigan School of Education, was the principal author of an amicus brief in the appeals court case. She cited research on the poverty rates in Detroit as well as the inequitable conditions in Detroit schools. Although the court settlement is a promising step, Moje said there is still a long way to go regarding legislation.

In the settlement, the state agreed to provide $2.72 million to fund various literacy-related supports. This funding comes from the governor’s budget and does not require legislative approval. Additionally, the governor agreed to propose legislation that would provide Detroit Public Schools Community District with at least $94.4 million of funding for literacy-related programs and initiatives.

As Moje noted, “The settlement has the potential to make profound changes in DPSCD’s education opportunities, but the extent to which the changes are truly powerful will depend largely on the state legislature.

The proposed legislation would support three major long-term changes: more professional development for teachers, literacy coaches to assist teachers, and literacy specialists to assist students in the classroom. If funds are supplied, DPS would also be granted more learning materials, such as up-to-date textbooks and technology resources. Moje highlighted the importance of adequate literacy instruction, citing that many Detroit youth are reading four to five grade levels behind their current grade while in high school.

“I believe deeply in education as a way of achieving justice and redressing injustices. It’s more than just giving everyone opportunity, it’s also about taking action to fix past wrongs,” Moje said. “That has always been my passion — I study adolescent literacy so I see really the fallout of not paying attention to literacy development. It was really important to me to be able to do something.”

Moje has been engaging in educational research with DPSCD since 1997. When she was approached by lawyers involved in Gary B. v. Whitmer, she was eager to serve as an expert witness because of her own experience through the years witnessing firsthand the inequities that DPS school children experience in their education.

“We’re talking about equitable opportunities, not just equal,” Moje said. “What we’re seeing is that after years and years of disenfranchisement… it’s not possible to give everyone the same funding and say that that’s equality because in fact many districts are so disadvantaged by the way funding has played out and by our systems that are oppressive and unjust that they need more money than other settings, and that’s what inspired me. I am working on trying to achieve educational equity and justice through my research, but I can also use my research to work on this through legal means.”

Moje detailed in the brief how schools in cities outside of Detroit receive adequate funding and thus more adequate literacy instruction, highlighting a “gross misalignment in Detroit between children’s needs and school funding and other supports for teaching and learning.”

Because Michigan only funds part of local school districts’ expenses, schools are expected to raise funds on their own for maintaining or improving older school buildings. Through local property taxes, wealthier districts can often better afford building maintenance and academic materials.

COVID-19 has also been a major factor in highlighting the disproportion of resources. With the switch to remote learning in March, DPSCD reported that early on that less than 10% of DPS schoolchildren could access online curricula.

“I’m very worried about a widening of the opportunity gap,” Moje said. “I think that what COVID has done for us has really laid bare the vast inequities in our whole society — certainly health disparities, economic disparities, education opportunity disparities, but it’s also revealed to us how dependent we are on our schools. People have been taking schools for granted for so many years, and suddenly our schools are having to create opportunity when vast numbers of our students do not have the technological resources to try to maintain the education that they should be having. This pandemic has demonstrated for us the role that schools play in our society, and it’s a much bigger role than people have acknowledged in the past.”

Through the Connected Futures Project, a $23 million program sponsored by DTE Energy Foundation, Quicken Loans Community Fund, the Skillman Foundation, General Motors and the Kellogg Foundation, students can receive wireless tablets and six months of internet access for free. The initiative has increased access to technological resources for 51,000 students and families in Detroit.

Before they were able to get the technology tools they needed, schools were reproducing paper packets and handing them out to families picking up food. Moje said this is one example of how the virus has only highlighted the inequities in our schools and the important role they play in our communities.

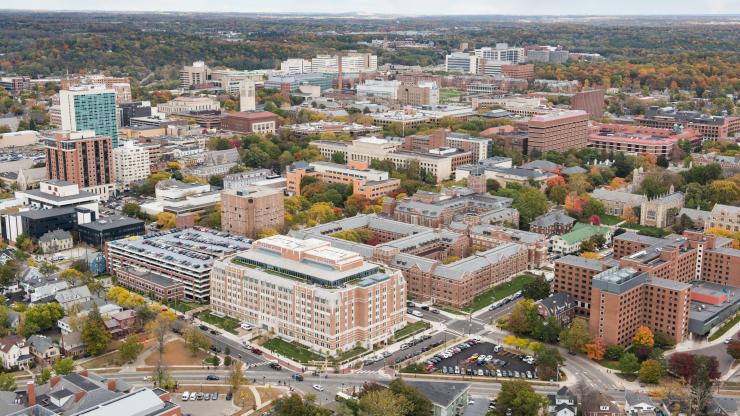

Moje has also been instrumental in the development of the new School at Marygrove, a collaboration between the University of Michigan and the DPSCD. The new initiative focuses on a “cradle-to-career” educational campus, which will serve students throughout their lives, from prenatal care to college. The K-12 school will eventually serve about 1,000 students per year with an adapted project- and place-based curriculum focusing on engineering and design skills taught through a social justice lens. Moje said the school is emblematic of the changes in schools she and many others want to see for the Detroit community.

“It’s all about the kind of change that the community wants to see,” Moje said. “It’s all about these young people being members of a community, and really leading the change into the future. It’s about being decision-makers and having a voice.”

Moje explained how U-M plays a fundamental role in Detroit and education, and her commitment to the university’s investment in education with its surrounding communities.

“I think it is the university’s responsibility to be engaged with the city of Detroit,” Moje said. “It’s not about the University of Michigan coming in and helping the city, it’s about having a relationship that is mutually beneficial and generative. The commitment to educational equity and justice compels me to believe that every child in every city across our state deserves the very best education possible.”