Designing the Future of STEM Education…and Educators

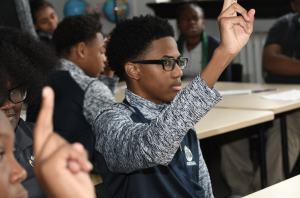

On September 3, 2019, excitement was high on the soon-to-be-former campus of Marygrove College. Barely three months after the announcement that the 92-year-old college would close its doors at the end of 2019, the 53-acre campus on Detroit’s west side was brimming with new life. But instead of college students, dozens of teachers, administrators, and community members were on hand to welcome a new cohort of 120 ninth graders to their first day of school.

Through an innovative partnership with Marygrove, Detroit Public Schools Community District, the Kresge Foundation, and the University of Michigan School of Education, this historic campus is being transformed into a groundbreaking “cradle to career” education hub. Beginning with the ninth grade in 2019, the school will expand over the next several years to include a full, STEM-focused K-12 continuum, an early childhood center, and post-secondary education and career training opportunities.

Dubbed “The School at Marygrove” (TSM), this new Detroit Public School is also home to the Michigan Education Teaching School which, modeled after teaching hospitals, offers an innovative approach for preparing new teachers to become outstanding urban teaching professionals. Just as novice physicians learn under the watchful eye of attending physicians, new teachers will be supported in their initial years of teaching by veteran educators.

In the Teaching School, undergraduate and graduate students enrolled in SOE’s teacher education program (“interns”) learn to use inquiry-based and student-centered approaches by teaching alongside one another, as well as expert (“attending”) teachers and university-based teacher educators. Once certified, interns are hired at TSM as first-, second-, and third-year certified “teaching residents,” during which time they will receive a full-time teacher’s salary from the district. As residents, they teach independently, but remain a part of an intergenerational team that includes expert teachers as supervisors and mentors, and undergraduate interns as mentees. After they complete their residency, they will apply for teaching positions in other schools, opening the residency positions to other newly graduated novices. This infrastructure will allow ongoing cycles of structural, pedagogical, and curricular innovation.

As TSM’s first teaching resident, Sneha Rathi is taking on one of the school’s core courses: Introduction to Human Centered Design and Engineering. As a STEM-focused school, every ninth grader will take the course, which will serve as a foundation for the academic work they will do as they progress through twelfth grade. Rathi graduated from the SOE’s Secondary Teacher Education program with a major in biology and a minor in history. She also holds a BS in biology from U-M’s College of Literature, Science, and the Arts.

While there are a variety of curricula that exist for high school engineering courses, Darin Stockdill, the Instructional and Program Design Coordinator for SOE’s Center for Education Design, Evaluation, and Research and a member of the SOE team supporting curriculum design work at TSM, explained that “we decided not to purchase a curriculum. Available packages tend to be focused more toward students who don’t look like our Marygrove students. In other words, they are designed for white, middle-class males. We wanted to develop something that was more inclusive, and we wanted the opportunity to be able to build it in partnership with instructors.”

The new curriculum, which focuses on Human Centered Design (HCD) and design thinking, was developed by an SOE team led by graduate student Jacqueline Handley and research investigator Carolyn Giroux, and supported by Stockdill. Rathi has been working with the project team since June, when they helped her to “workshop” the curriculum before the beginning of the school year. The team will continue to provide support as Rathi makes the curriculum her own and as she gets to know her students over the course of the year. Handley will also have an ongoing role in the classroom observing and assisting with the curriculum.

Handley explains that Human Centered Design “includes design areas such as user experience design, participatory or community design, and socially engaged design. HCD explores solutions that respond to the needs of humans, addressing concerns that humans identified or even created. In some ways, it operates counter to design initiatives that would emphasize advancing technology over human interest. In taking on this type of process with youth, we try to do it in ways that are socially just and rooted in the community. This means engaging with, among other things, the inequities in previous designs, the histories of a place, and the needs of all stakeholders.”

“This curriculum is also designed to integrate the skills and literacies that students come with,” Giroux notes. “Our goal is for the course to live at the crossroads of a standard engineering course and what the students themselves bring to the table.”

The development of the course was based on research on similar work (like the SOE’s Sensor’s in a Shoebox project) taking place in informal spaces, such as after-school and out-of-school programs. Because TSM is a new school inhabiting a temporary space until renovations on its permanent building are complete, the curriculum team felt that exploring design challenges within the students’ own school environment would offer compelling project challenges and fit within the school’s stated ethos of equipping its students to serve as the neighborhood’s (and city’s) next change agents while honoring the school’s theme: Leaders Designing Change.

Over the course of the school year, the class will take students through four design cycles:

- Process design – exploring and designing a process that makes the space more responsive to its students

- Product design – exploring how students can store, transport, and organize their belongings during school hours

- Penultimate design – a process- or product-oriented project, based on student work and interests situated within the school community

- Capstone design – a student-led project, potentially based on design problems presented by outside partners and stakeholders addressing student-raised interests or concerns in the school or surrounding community

Each design cycle explores design-based processes and unpacks the language and literacies of the engineering world. “It will be an exciting year,” Rathi says, “but there will definitely be challenges, which include figuring out exactly how to bring standard engineering processes—such as implementation and iteration—into the classroom, and determining what classroom norms and supports will need to change. This involves developing a certain comfort level for students (and teachers) with the reality of the design process, which includes outside demands, failure, and ambiguity.”