For LEAPS Students, “Engagement” Means Partnership

From a family shelter to a youth-led tech incubator, meet some of the organizations LEAPS partners with across the city of Detroit

Djennin Casab is a professional matchmaker.

As the Community-Engaged Learning Coordinator for the Learning, Equity, and Problem Solving for the Public Good (LEAPS) undergraduate program, Casab is responsible for pairing students with Detroit-based organizations for community-engaged internships.

"My main role is to create, develop, and nurture external partnerships so that our students can be matched according to community-defined needs and student interests," says Casab, who draws on years of experience working in Detroit in the higher education field with a focus on community-engaged learning. She emphasizes that each relationship with an organization is a partnership.

"Community partners are fulfilling a function of need in the city—whether it's tackling homelessness, food deserts, or education—anything that is a societal need. Our students have different interests. My role is to match them with organizations and supervise the relationships to make sure that they are mutually beneficial."

According to Program Chair Barry Fishman, community-engaged learning is the heart of the LEAPS program. "One of the most effective ways to learn is through application. LEAPS students are actively building connections between their classroom-based learning and their community-engaged learning. This creates both more engagement and more meaningful learning."

In the winter semester of their freshman year, the first cohort of LEAPS students engaged with partner organizations across the city of Detroit, including the Coalition on Temporary Shelter (COTS) and Google Code Next.

COTS was founded in 1982 when a group of local churches and local leaders observed a rise in homelessness among single men.

"Initially, we partnered with a church to provide shelter and basic needs for men who were experiencing homelessness," says Aisha Morrell-Ferguson, COTS's chief development officer. "The following year, we purchased the Old Imperial Hotel here in Detroit. It underwent a million-dollar renovation and became an expanded place to be able to serve those needs." Instead of a traditional shelter that provided shared space in a large, open room, the renovated hotel building afforded privacy and dignity for those who were experiencing housing instability. The model was so successful, it became an inspiration for other organizations that were starting up around the country. The hotel building also had the capacity to serve more than just emergency shelter needs. In time, COTS added transitional housing, and eventually long-term supportive housing, for those with long-term needs based on disability and addiction.

"We went from serving only single men and single women to eventually serving families," says Morrell-Ferguson. At that point, the organization observed another facet of support their clients needed. "You can't take your children with you to a job interview, and it's not always easy to take them with you when you're searching for housing, either." So in 2006, COTS opened a childcare center, Bright Beginnings, to support families as they were working to reestablish stability.

In 2015, COTS saw a rise in family homelessness. "Here in Detroit, there's a bunch of agencies that partner and work together. Many of them were able to meet the needs of single men and single women, but not many of them were able to meet the needs of families and help families stay together," says Morrell-Ferguson, again observing the needs of the community. "Because of our history and unique positioning to support families, we decided to reach out to those partners and say, ‘Look, if you continue to work with single men, single women, even unaccompanied youth, we'll continue to work with families and preserve our shelter services for families only.'" The change in service meant that those seeking shelter at COTS had to be accompanied by a minor.

At the same time, the organization adopted a coaching program called Passport to Self-Sufficiency, a framework that brings together partners in service to support families in five key domains: housing and family stability, health and well-being, economic mobility and empowerment, education and job training, and employment and career development. Working with a mobility coach, the head of the household works to establish objectives across the five domains. These objectives are entirely participant-driven, fostering a sense of ownership and empowerment. To facilitate progress, individuals receive both individualized and group coaching, gain access to resources from community partners, and are motivated by incentives, all aimed at nurturing economic self-sufficiency and creating stable living environments that yield a lasting, multigenerational impact.

"We know that things don't happen overnight," says Morrell-Ferguson. "A family experiencing homelessness often has a very big hill to climb. This support is necessary for a period of time to help them maintain that stability and then to be able to launch and change the future for their children. We believe in two-generation impact: that it's not enough just to support the parents and their needs, but we have to support the children and their needs just the same, and help them in aiding one another to build momentum toward success."

Bringing together partners through the five domains of the Passport to Self-Sufficiency framework helps COTS ensure that all the needs of the families it serves are being met. "In addition," says Morrell-Ferguson, "it gives people who have not experienced the crisis of poverty or homelessness an opportunity to engage with and work alongside those who have. It enables them to advocate for changes, to be able to collaborate on policy initiatives, to be able to create new solutions. It invites everybody to the table instead of keeping people away and trying to create solutions for them."

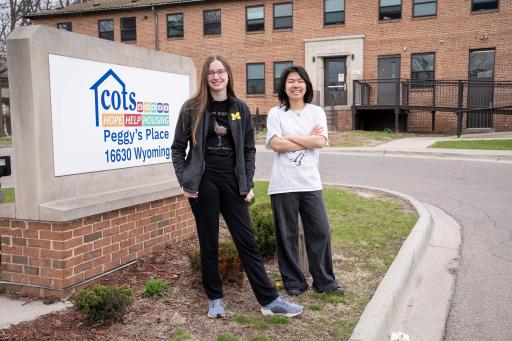

This spring, LEAPS students Angela Zhou and Samantha McDole began their community-engaged placements at COTS with the same approach: as partners, they wanted to learn what COTS and the families it serves were in need of.

"They walked through our shelter to see how things are working right now. They learned what has worked well, and they also learned the challenges of what has not worked so well," says Morrell-Ferguson.

COTS receives many donated items, but there hasn't always been a space or a system to receive and process them. Over time, the donations have piled up. "It's hard to maneuver and assess what we have, what we need, and what we don't need," says Morrell-Ferguson. As part of their placement, Zhou and McDole began to sort donations and organize the space for donated items so they can be distributed in a manner that upholds the dignity of those who have need of them. What items COTS didn't need would be shared with partner organizations who would be better able to make use of them.

"One of the things that influenced how I went about approaching the spaces we were given was something Aisha told Angela and me early on in the partnership," says McDole. "She told us to always question why something was being done the way it was, instead of just accepting it. And if it wasn't relevant anymore, to change how things were being done."

Although their placement was originally scheduled just for Friday afternoons, the LEAPS students soon began coming to the shelter on other days as well, to spend more time working on the donation room. COTS's shelter is located on Wyoming Avenue, right next to the Marygrove campus, making it convenient to come over after class. By mid-semester, the new relationship between LEAPS and COTS was deepening—what had begun as a placement had transformed into an ongoing project. In the future, Casab hopes that the donation room can be managed by LEAPS students. "Right now, we're just starting to clean it up, but it's something we as a program want to take responsibility for going forward. Every semester, managing the donation room will be a first-year project for LEAPS students."

For their internship with Google Code Next, LEAPS students Junho Lee, Zahraa Teli, and Kyra Han met with high school students who participate in the free, computer science education program that provides skills and inspiration—plus college preparation—for long and rewarding careers in computer science-related fields.

"I am interested in educational inequity and how policy can be used to effectively bridge those gaps," says Teli. "Partnering with Code Next gave me an opportunity to explore those ideas in practice by working directly in a community I've grown deeply connected to through both living in Detroit and studying its history."

Code Next serves Black, Latine, and Indigenous youth who live in the vicinity of its labs which, in addition to Detroit, are located in Oakland and Inglewood, California, and Chelsea, New York. Since 2015, Code Next has welcomed more than 10,000 students into the program nationwide. Over 90 percent of its graduates are pursuing higher education, and more than 88 percent are majoring in a STEM field.

The Detroit Code Next Lab was the first tenant in Michigan Central Station, the modern incarnation of Detroit's iconic former train station and the centerpiece of the 30-acre Michigan Central innovation campus. The campus, which also includes the Newlab at Michigan Central building neighboring The Station, has grown to include a diverse ecosystem of more than 100 companies and startups since its opening last year. Startups in Newlab come from all over Michigan, across the country, and around the world. They are dedicated to shaping the future of mobility and are working to reestablish Detroit as a global leader in innovation.

"We're teaching students how to become technology leaders," says Nando Felten, Community Manager for Code Next Detroit. "Students are learning how to start their own companies and we're partnering with local companies that are right next door to us in Newlab to bring their ideas to life."

The Code Next Detroit Lab started in 2022 and currently serves over 100 students who participate in after-school and weekend programming, which is offered year-round. When they arrive, students are welcomed with a hot meal, followed by a community circle. At the lab, participants have access to coaches, state-of-the-art technical equipment, and content ranging from Javascript programming to user experience (UX) design. They can also choose to participate in various Code Next clubs relevant to their interests including iOS development, game design, entrepreneurship, and engineering.

"I am interested in educational technology, so partnering with Code Next gave me an opportunity to understand the importance of providing the right resources for youth to thrive," says Lee.

Felten sees Google Code Next as an incubator for the tech hub in Detroit. "We have built a model for how industry, education, and the community can collaborate to drive real impact," he says. "Having student voices heard, and having students be able to create and design places and spaces means a lot. A lot of the time, students in Detroit are just users of technology or consumers of their own culture. We're trying to figure out how to make them creators of their technology and of their culture. Through Code Next, students see that that potential does exist."

Felten, who grew up just down the street from Michigan Central, played football in high school. He remembers the intensity of training—he went to practices before and after school, and in the off-season his coach encouraged him to play other sports and to stay active. The conditioning and layers of accountability helped Felten excel. Drawing on that experience, Felten and Code Next aim to inspire the same focus and attention to preparing for a future in computer science. "We've incorporated a new curriculum that hopefully gives students the opportunity to practice and put the time and effort in to be excellent in computer science in the same way that our system in this country is already set up for sports."

Felten attended U-M as an undergraduate before earning his master's degree from the Marsal Family School of Education. As a graduate student, he served on the team helmed by professors Barry Fishman and Leslie Rupert Herrenkohl to develop the LEAPS program. It was a full-circle moment for Felten to have members of the first cohort of LEAPS students intern with him at Code Next. As interns, Lee, Teli, and Han helped the high school students prepare to present at the second annual Detroit Youth Mobility Summit, a launchpad for youth-led mobility solutions and collaborations with peers and policy and industry experts. Code Next partnered with YouthTank Detroit, a youth-led nonprofit focused on entrepreneurship, to participate in the summit, which took place at Newlab.

"The Mobility Summit allows students to grab the wheel and be the drivers of their own destinies around mobility, not just in the sense of transportation—which is really needed in Detroit—but also social mobility, the ways of getting ideas and information conveyed," says Felten. "Often when decisions are being made, there is no seat at the table for the youth voice. So we're giving students the opportunity to let Detroit—and the world—know what they have to offer."

"Working with Code Next exposed me to ways in which Detroit youth are readily prepared to cultivate the agency to innovate and create solutions for their community," says Han. "I saw how youth directed event planning efforts for the 2025 Detroit Youth Mobility Summit through active leadership and creative thinking."

Although LEAPS participants are first-year college students, they are near peers of the Code Next high school students. As they helped with preparations for the Youth Mobility Summit, they were also given the opportunity to reflect on what it meant to participate in a program like Code Next as a high school student. "The LEAPS students are seeing high schoolers think very proactively, very consciously, about how they're helping to shape their community. And it gives LEAPS students a chance to ask what they might have done in their own communities if they'd been given a chance like this in high school."

In turn, the reciprocal nature of the partnership between Code Next and LEAPS gave the high school students a connection to the University of Michigan, where many of them hope to attend college. "It gives them a visualization, this realization that ‘I can be there, too,'" says Felten.

Beyond the first-year placements, community-engaged learning is threaded throughout the four-year LEAPS curriculum. Guided reflection is a key component of these high-impact practices, helping students make meaning of their experiences. Opportunities for journaling are built into courses, and dialogue and discussion take place in Forum, the homeroom-like class where students draw connections across their different areas of learning.

"They think about what they've experienced as students, and then they think about themselves," says Casab. "They think about where they come from, analyzing their own lives and the intersectionality of their assumptions, privilege, and oppression." Without the guided reflection component of community-engaged work, she adds, there is potential to do harm. "If you don't understand the context, the culture, the history of the community you are collaborating with, you can perpetuate stereotypes and negative assumptions." However, if the experience is curated in a way that allows for meaning-making and critical reflection—as it is in LEAPS—the high-impact work "makes you a more empathetic person," says Casab. "It makes you a more compassionate and non-judgmental person, and someone who really wants to be a good citizen."

As LEAPS relationships with partner organizations continue to develop, the program looks forward to bringing them together in the LEAPS Community Partner Network.

"We follow the philosophy of asking our partners what they need, and what they want this network space to be," says Casab. Perhaps the meetings will be social, she explains, or maybe they will be a place to discuss wellness or professional development. "The first meeting is being called by LEAPS, but it's going to be unstructured. We'll ask ‘What would you like this space to be?' so that we can all participate in the creation of whatever the network is going to look like."

Casab, who was born in Mexico, considers herself an "adopted daughter" of Detroit. She approaches the cultivation of partnerships with humility and curiosity. "I want to know about the culture and I want to know how the communities are tackling the problems that they have. If you're not humble, the doors are not going to open. The great thing about LEAPS is having students who also have that curiosity, and who also want to know how they can become learning leaders and how they can apply their skills for the public good."