Breaking Down Barriers and Building with Tools in Afterschool Makerspaces

Angela Calabrese Barton’s research shows the impact STEM education in informal learning environments can have on communities and the world

“The vast majority of kids’ time is not actually spent in school,” says Professor of Educational Studies Angela Calabrese Barton. “So informal learning environments play a really important role in terms of providing both compensatory education for what students might not be getting in school, as well as enlightenment to build beyond what they are learning in school and to open up pathways that schools might have foreclosed because of lack of resources and opportunity.”

As part of both her research and practice, Calabrese Barton teaches after-school STEM in community centers and makerspaces. With a focus on equity and justice, she is interested in how informal learning environments can act as a mechanism for breaking down cultural and institutional barriers.

“For decades now, I’ve been working in community settings like afterschool programs and science centers to think about not only how to design learning environments that support justice-oriented outcomes, but also how to build capacity with educators to engage in pedagogical practices and curriculum design in order to support these justice-oriented outcomes,” says Calabrese Barton.

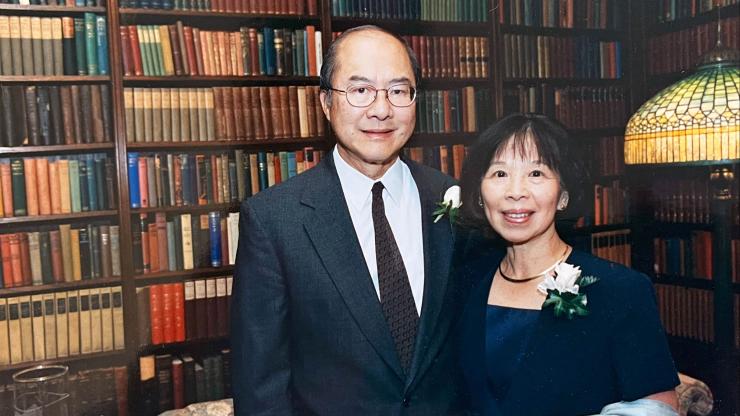

Since 2007, she has collaborated with Carmen Turner, Executive Director of the Boys and Girls Club of Lansing, on the Green Energy Technologies (GET) in the City program. GET City is focused on youth development in energy and environmental science, engineering, and information technologies. The program is built on the idea that meaningful learning happens when youth engage in authentic investigations of local problems, and have scaffolded opportunities to communicate with and educate others about those investigations.

Typically, explains Turner, “Boys and Girls Clubs are situated in urban areas where there are fewer resources, and where, a lot of the time, the kids are the first in their family to go to college.” From the outset, she was intrigued by GET City’s potential to engage children who didn’t necessarily identify with STEM. Where they might worry about how they would be graded, or judgment from peers, Turner recognized the power of the club’s informal setting. With those barriers removed, she watched students develop self-esteem.

“I would go into Angie’s room and they would be doing science and engineering activities. I’m thinking, ‘Okay, they don’t know that they’re doing science and engineering because if you told them they were, they would say, “I can’t do it. I’m not interested. It’s boring. People tell me that’s not me, that I should go into something else.” In fact, that’s what Turner herself, a Woman of Color, was told when she was growing up. “So when Angie explained to me that the work could be done starting at the fourth and fifth grade, I said, ‘Yes, what do we have to lose? This is absolutely wonderful.’”

In the beginning of their research-practice partnership, recalls Turner, Calabrese Barton wheeled a cart with computers on it into any space she could find in the Boys and Girls Club facility to teach. Today, the GET City program operates out of the Dart Innovation Lab and Makerspace, engaging youth aged eight and up in deep and meaningful STEM learning (knowledge and practices), technical/engineering design work and problem-solving, critical thinking, and individual and group work.

“When Angie and I started, I remember her saying, ‘I’m not necessarily trying to create all of these engineers and scientists,’” recalls Turner. “Her idea was to help young People of Color understand strategic thinking. Because when you strategize, you become confident and good at everything. And that’s what started happening in school.”

The roof of the Boys and Girls Club had started leaking, and Turner was getting quotes from roofing companies when the kids approached her. Because they had learned about environmental impacts in GET City, they wanted a green roof. Even though it was out of her budget, Turner was listening. The kids researched alternatives, and proposed a white roof instead—a solution that would be energy-efficient and environmentally beneficial to the community. They found a company who could do the job and visited their facilities. With the kids’ research, Turner and Calabrese Barton put together a proposal that garnered $65,000 from the Dart Foundation to fund the project.

“We have a white roof because of the work that those fifth, sixth, seventh, and eighth graders put together—and it’s because of what Angie instilled in them about change,” says Turner.

When the club installed skylights, the kids watched how the sun traveled across the sky over the course of a day, and advised where they should be placed. When they wanted a makerspace, they presented to the Boys and Girls Club board, having the body of adults participate in activities they didn’t have the materials to complete. They wanted the board to feel their own frustration of doing activities without the proper resources. Once more, the Dart Foundation provided funding to make the makerspace a reality. Turner ticks off places where the GET City youth have made presentations: to the mayor of Lansing, in Washington DC, to Calabrese Barton’s colleagues.

“These kids are action,” she says.

In 2015, Calabrese Barton was awarded a Distinguished Fellowship from the William T. Grant Foundation to research the potential of makerspaces to create equitable learning opportunities for youth. To do this embedded research, she began another research-practice partnership with Lansing’s Impression 5 Science Center.

Micaela Balzer, Director of Innovation and Learning at Impression 5, had noticed that the kids who attended the science center’s exhibits and programs stopped coming around age 12. She wanted to figure out how to engage teens, and how to shift its demographics to reflect those of the city of Lansing, which was more diverse than the science center’s mostly white and affluent membership. Finally, if its new makerspace was intended to be a place for teens, she wanted to know what teens would want out of it.

One of the first projects Calabrese Barton and Balzer worked on together was the formation of the Youth Action Council (YAC), a body of youth who would have a voice in what the makerspace would look like. They put out the call for participants to existing science center members as well as the public. Calabrese Barton also reached out to Turner to create a pathway for STEM-engaged Boys and Girls Club members to join the YAC.

“My blessing was to have the Boys and Girls Club kids be a significant part of Impression 5—more than just going to visit and look at exhibits—but making a change and having a voice,” says Turner.

Comprising about 20 youth, YAC members ranged from fifth grade through high school. Participants and their families got free membership to the science center, and were encouraged to take any workshops they wanted. “The YAC is highly diverse in terms of race, socioeconomics, and even geography,” says Calabrese Barton. “Having that wide range ended up being a really powerful aspect of the YAC, because many of the younger kids stayed in it for five, six, seven, or eight years. The older kids became mentors to the younger kids, and as new kids came on, the more experienced members would mentor them.”

When Impression 5’s new makerspace—the Think Tank—opened in 2017, the YAC’s input was evident in every aspect of its design.

“They wanted to create a space that was very different from what they were used to,” says Balzer. “Even details like the chairs were important. One of the kids said, ‘These chairs look like school chairs,’ so automatically they were boring. That filter of how something looks and then the emotions that it conveys based on its appearance really helped shape the space.”

“They were adamant they needed a ‘chill zone’ in the makerspace. So there’s a separate room for that. They wanted it to have a couch and a rainbow carpet,” says Calabrese Barton. “It literally is a place where kids, when they’re frustrated with a project they’re working on, can go and chill out. They also wanted rough draft projects to be displayed throughout the room so that everybody would feel like they could do it too. Instead of just seeing these perfect, beautiful final projects, which is often what you see displayed in a science center, there’s a place for people to display work in progress.”

The Think Tank has circuitry, woodworking, and robotics stations. There are Legos®, cardboard, and textiles for building. There’s soldering equipment. The founding members of the YAC built nameplates using woodworking, crafting, and circuitry materials to make their names stand out on wooden boards. The nameplates adorn the walls of the Think Tank.

“The workshop tables are so well loved, they have drill marks and nail marks and paint all over them,” says Impression 5 Programs Manager, Betsy Mappilaparampil. “They’re all scratched up, but in the most beautiful way because it’s like a history of the work that has been done in this room.” Impression 5 offers a range of workshops in the space. The idea, says Calabrese Barton, is to “always make something you can bring home, to have something that’s meaningful to you.”

When the Think Tank was complete, says Calabrese Barton, “it changed how we at the science center thought about what it meant to design new exhibits and new spaces.” The YAC, which meets once a month in the Think Tank, was asking questions like, “Who’s in the science center?” and “How are different lives represented in the science center?” Their discourse prompted Balzer and Impression 5’s leadership to question what they should do next.

Meanwhile, Calabrese Barton had become involved in a large partnership grant funded by the Wellcome Trust and the National Science Foundation to work with researchers who were embedded in informal science centers in four cities—two in the U.S. and two in the U.K. Known as the Youth Equity and STEM project (YESTEM), the international research-practice partnership focused on understanding and supporting equitable practices in informal STEM learning. In Lansing, Calabrese Barton worked closely with her partners at the Boys and Girls Club and Impression 5 to figure out what those practices are.

One of the biggest challenges in informal learning environments, notes Calabrese Barton, is a lack of resources to support capacity building. Through the YESTEM project, the partner science educators worked with the researchers to identify beneficial teaching practices. “Often we don’t know our strengths until someone else points them out,” says Impression 5 Operations Manager Nik McPherson. “Being able to have those reflection moments to celebrate with a researcher who was observing me was really helpful.”

Over the course of two years, YESTEM gathered data by documenting the youth perspective in youth participatory ethnographies and the educators’ perspective in participatory portfolio construction. Working in research-practice partnership teams comprising educators, researchers, and youth, they identified consequential moments in the data that they wanted to zoom in on more closely.

“From the analytic work that we did together over years—not just in Lansing, but in our other partner cities—we identified nine practices that we think really matter in supporting justice-oriented teaching and learning in informal settings,” explains Calabrese Barton. One of those practices is reclaiming.

Once the Think Tank was open, the YAC continued to have conversations about reclaiming the science center to make it truly reflective of everyone who is involved in science. When talking about who is seen and unseen in science, their attention was drawn to the classrooms in Impression 5, which were named for famous figures including Newton, Galileo, and Edison.

“Here we were, yet again, a science center that is willing to support youth in having these conversations, but we were also part of the system that continues to only showcase white male scientists,” says Balzer.

The YAC spent a year researching and considering who else had made significant contributions to science, but who were not represented, and how they might be. Collectively, the group landed on Katherine Johnson, the pioneering mathematician who figured out the paths for the first NASA spacecraft to orbit earth and to land on the moon, but who was also impacted by racism and sexism. When the YAC decided to rename a room in the science center for Johnson, they created the signage for the room, changed its color scheme, and hung a photograph of the mathematician in the space, communicating her story through different design elements. Today, the Katherine Johnson Room has become a prominent community space, hosting groups and classes. It’s where everyone wants to have their birthday.

“Once you start reclaiming spaces, or noticing and taking action,” says Balzer, “it becomes part of who you are. Their critical observations did not just stop.”

Next, the YAC undertook the reclaiming of the Big Mouth, an iconic sculpture that has been part of Impression 5 since its founding. All along, it had always been a large Caucasian mouth with blue eyes. The sculpture was in need of restoration, and already a funder had come on board to make the necessary repairs. So the YAC began prototyping what the Big Mouth could look like in its new iteration, and how it could be remade to better reflect the Lansing community. Using 3D renderings of the sculpture, the youth designed plans and voted on them, ultimately deciding to repaint the Big Mouth in a pixilated collage of 26 different skin tones with brown eyes. In addition, they produced educational materials and new signage to explain how the Big Mouth's design represents the science center's efforts to be inclusive and described the importance of breaking down barriers to STEM participation. Today, visitors often approach the Big Mouth and hold up their arm to literally find themselves represented in the sculpture.

In April 2023, a group of YAC participants took the train to Chicago to present their research in a project titled, “Reclaiming our Science Center towards Social Justice,” at the American Educational Research Association (AERA) Annual Meeting. Their guiding questions were: “How does the science center maintain injustices such as racism? What design actions can we take to make our science center more humanizing and just for minoritized communities?” Reviewing the participatory design-based research the group had done since 2016 to reclaim the science center “from colonial, white, heteropatriarchal histories,” the presentation highlighted how the YAC had made space for youth to take back power over how their lives, histories, stories, and communities are represented.

“The youth were able to present to other youth teams from across the country, and around the world,” says Calabrese Barton. “The local work they had done felt significant in that they could see that they were changing not just the physical space of the science center, but also the practices that take place there, the expectations and the hopes. At the same time, they were learning about themselves, and issues of justice in STEM. Going to AERA helped them see that other people outside their community are interested in these issues and can learn from them. It gave them a whole different scale to see that their work had deep significance beyond just the Lansing community.”

Structural inequality in education is prevalent, and hard to fix. For an example, Calabrese Barton points to the difference between a high school in an affluent suburb and one in the city of Lansing. One offers 22 different science courses, where the other offers just seven—those that cover the basic requirements for graduation—because that’s all the school has the resources to provide.

“Systemic inequities are hard to fix in the moment, and kids are living their lives in the moment. What else can we do?” she asks. “The YAC has been able to provide enrichment and compensatory experiences to the youth—they’re doing action research, they’re writing and publishing papers, they’re presenting at conferences. They’re seeing how their research makes a difference in the here and now in the actual design of spaces and in the lives of real people. That’s going to make a huge difference, and open up new opportunities for them, beyond what they are able to get in high school.”